Every day, US-based Uyghur journalist Gulchehra Hoja tries to call her family in the Chinese region of Xinjiang. Sometimes she tries up to 20 different numbers, just hoping that someone will pick up.

“I know they won’t pick up the phone, but I try … nobody picks up,” she told CNN in an interview from her office in Washington.

She doesn’t expect an answer because 23 of her family members – including her aunt, her brothers, her cousins – have disappeared, along with tens of thousands of other ethnic Uyghurs inside enormous state-controlled “re-education camps.”

Hoja, who works as a journalist for US government-funded Radio Free Asia (RFA), says her brother was the first in the family to vanish in September 28, 2017.

“This is my brother and this is me,” she says, holding up a picture. “This was taken in summer 2000, it’s my birthday … this is my last picture with him …. (Now) he is missing. We don’t know where he is now.”

Her aunt, who raised her, and then her cousins vanished into Xinjiang’s vast detention system, without any explanation or trial. She says her parents, last she heard, were under house arrest, unable even to go to a doctor without permission. But even they stopped taking her calls a month ago.

An estimated one million Uyghurs, a predominantly Muslim ethnic minority in western China, are being held in camps across the region, according to a US congressional report.

The Chinese government has never explained the disappearances, which began in 2017, nor said how many people are being held in the camps, which they insist are “vocational training centers” that local “students” are happy to attend.

Defending his country’s human rights record at a United Nations forum in early November, China’s Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Le Yucheng said that his country had made “remarkable progress” in the past four decades, including “lifting more than a billion people out of poverty.”

But many other countries remain harshly critical of Beijing’s record, especially in regards to the Xinjiang camps. More than a dozen states including Australia, Germany and the United States have called on China to dismantle the camps and release those detained.

“They are transformation centers, and they really are aimed at completely altering Uyghur culture and identity. It’s kind of a surreal practice, I would say, that is definitely unprecedented in the 21st century,” Sean Roberts, director of the International Development Studies Program at George Washington University, told CNN.

Hoja goes even further. She describes it as “cultural genocide.”

‘Brainwashed’

Beijing has had a long and fractious history with Xinjiang, a massive, nominally autonomous region in the far west of the country that is home to a relatively small population of around 22 million in a nation of 1.4 billion people.

Although the ruling Communist Party says Xinjiang has been part of China “since ancient times,” it was only officially named and placed under central government control after being conquered by the Qing Dynasty in the 1800s.

The predominately Muslim Uyghurs, who are ethnically distinct from the country’s majority ethnic group, the Han Chinese, form the majority in Xinjiang, where they account for just under half of the total population.

This, however, is changing fast. According to government data, in 1953 Han Chinese accounted for just 6% of Xinjiang’s total population of 4.87 million, while Uyghurs made up 75%. By the year 2000 the Han Chinese population had grown to 40%, while Uyghurs had fallen to 45% of the total population of 18.46 million.

Continued economic development has led to an increase in skilled Han Chinese migrants. The provincial capital Urumqi, Xinjiang’s largest and most prosperous city, is today majority Han Chinese.

“They named our homeland Xinjiang … Uyghurs prefer to call it East Turkistan because our land was called (that) before the Chinese occupied,” Hoja said, looking at the map of her home province. Xinjiang means “new frontier” in Chinese.

In the past decade, perceived “Sinocization” across Xinjiang has led to Uyghur unrest – and bouts of bloody ethnic violence.

The region has also been braced by acts of terrorism, often directed at authorities. In reaction, the provincial government, which blames the terrorist attacks on independence-seeking Uyghur extremists, has greatly expanded its efforts to control the local Uyghur population.

Under direction of Xinjiang’s Communist Party Secretary Chen Quanguo, authorities have cracked down hard on the Muslim beliefs and practices of the Uyghur population, including face coverings and long beards, Quran study groups and preventing government employees from fasting for Ramadan.

Anyone can be sent, under the flimsiest of reasons, to “re-education camps,” according to Hoja. “When my brother was taken … my Mum asked like, ‘Why are you taking my son? What he do?’ And the officer answered back, ‘His sister’s (in the US), is that not enough to take him?’” she said.

But Hoja believes the real reason he was taken was simpler than that. “They are targeted just because they are Uyghurs.”

Hoja claims up to 40% of the province’s Uyghur population, as many as four million people, could currently be held in the “re-education camps.”

“They are ill-treated there. They are tortured there. Even you cannot speak your own language in there, you are brainwashed,” Hoja alleged.

“Every day before your meal you have to sing a ‘red’ (communist) song, and say thank you to (Chinese President) Xi Jinping or the Communist Party.”

In defense of the government’s policy, Chinese state broadcaster CCTV aired footage inside what they term “vocational training camps,” showing smiling Uyghurs learning Chinese and skills such as sewing.

But Hoja challenged the idea that her family was in such desperate need of vocational training that they should be taken to the camps.

“My aunt knows more than three languages, she is also retired from the Xinjiang Museum, so what kind of education does she need to take?” she said.

‘The worst feeling in the world’

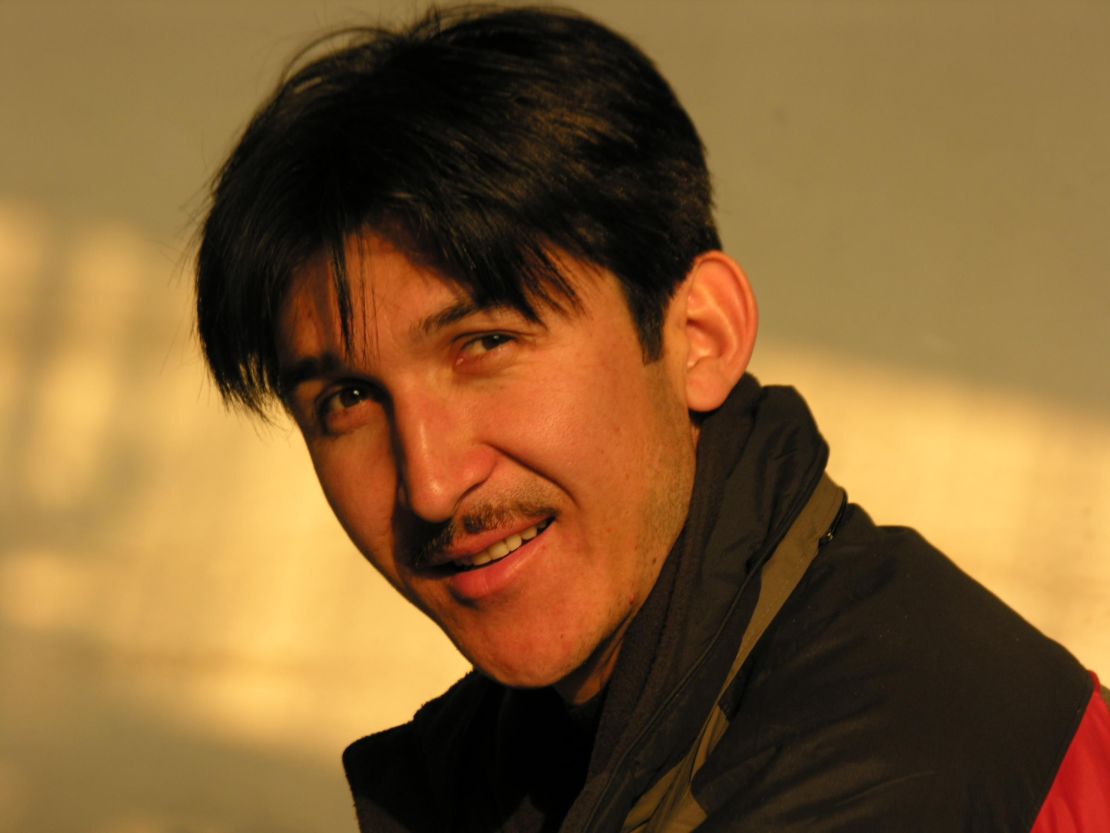

Mamatjan Juma, another Uyghur journalist working for RFA, said not knowing where your family was, or being able to help them, was “the worst feeling in the world.”

“Every day I think of them, the pain is there. Because it’s just like a kind of virus, it’s in your mind, the pain is there every night. They were in my dreams sometimes … You cannot do anything,” he told CNN.

A former teacher from a big family in the Xinjiang city of Kashgar, Juma, said Chinese authorities took away two of his brothers in May 2017.

“My last brother, the third one, the youngest brother was taken away this year, in February. And since then I’ve lost contact with my Mom and two of my younger sisters,” he said.

Like Hoja, Juma feels that working as a journalist in the US has led to negative consequences for his family. From 2010, he began to receive calls from his brother trying to convince him to come home. They only stopped when his brother vanished.

Juma said he is most concerned about his mother, who is severely unwell after suffering multiple heart attacks and being sent to hospital three times. “I don’t know what happened to her, if she’s been taken away, or something has happened to her,” he said.

He worries for those detained. “One Uyghur businessman told me that they were left like animals. They don’t have any facilities … They don’t have enough food,” he said.

The Chinese government claims its actions in Xinjiang, including the mass detentions and forced home stays by Communist Party officials, are designed to make the province more secure and prosperous.

Xinjiang Governor Shohrat Zakir, himself a Uyghur, told the state-run Xinhua news agency in October that since the crackdown “Xinjiang is not only beautiful but also safe and stable.”

But Juma told CNN Beijing is simply trying to “Sinocize” Xinjiang, remove the Uyghurs’ culture and identity and make them more like the Han Chinese majority. “They call it educate and civilize, but that’s not the case,” he said.

‘Critical location’

While a large part of the Chinese government’s crackdown in Xinjiang has centered on efforts to “transform” Uyghurs into model Chinese citizens, Roberts, the associate professor, said there may be ulterior motives for Beijing.

“If you look at the plans for (Chinese President) Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, Xinjiang is a critical location that will serve as the jumping off point for all economic expansion into Central Asia and South West Asia and really into Europe,” he told CNN.

The Belt and Road Initiative, a signature policy of Xi’s, plans to create trade corridors between Beijing and the rest of the world, through international infrastructure spending and diplomatic agreements.

The name references the Maritime Silk Road, which will run to Africa through South East Asia, and the Silk Road Economic Belt, which will connect Xinjiang to important partners such as Pakistan, Turkey and Russia.

“The Belt and Road is part of the reason that there’s such an urgency to clean up the Uyghur population in Xinjiang at the present moment,” Roberts said.

“What really concerns me is that, if it’s really the last chance to try to transform Uyghurs, what’s the next step if they decide that the Uyghurs can’t be transformed into a passive benign minority that’s loyal to the state?” he said.

Despite the threat of violence or abduction for her and her family, Hoja says she feels obligated to keep speaking out and working to raise awareness for the “voiceless” Uyghur.

Even with everything that’s happened, Hoja says, her dearest wish would be to return home, one day, to Xinjiang. “It’s my biggest dream … everybody wants to go back home right?”

CNN’s Rebecca Wright contributed to this article.