Chess is brutal. Chess is now cool.

Sitting barely a meter away from each other in a London amphitheater under the intense glare of spotlights and spectators are two twentysomethings who were once both prodigies.

They are competing in a too-close-to-call title fight for the World Chess Championship. They are, it has been said, making being smart “sexy.”

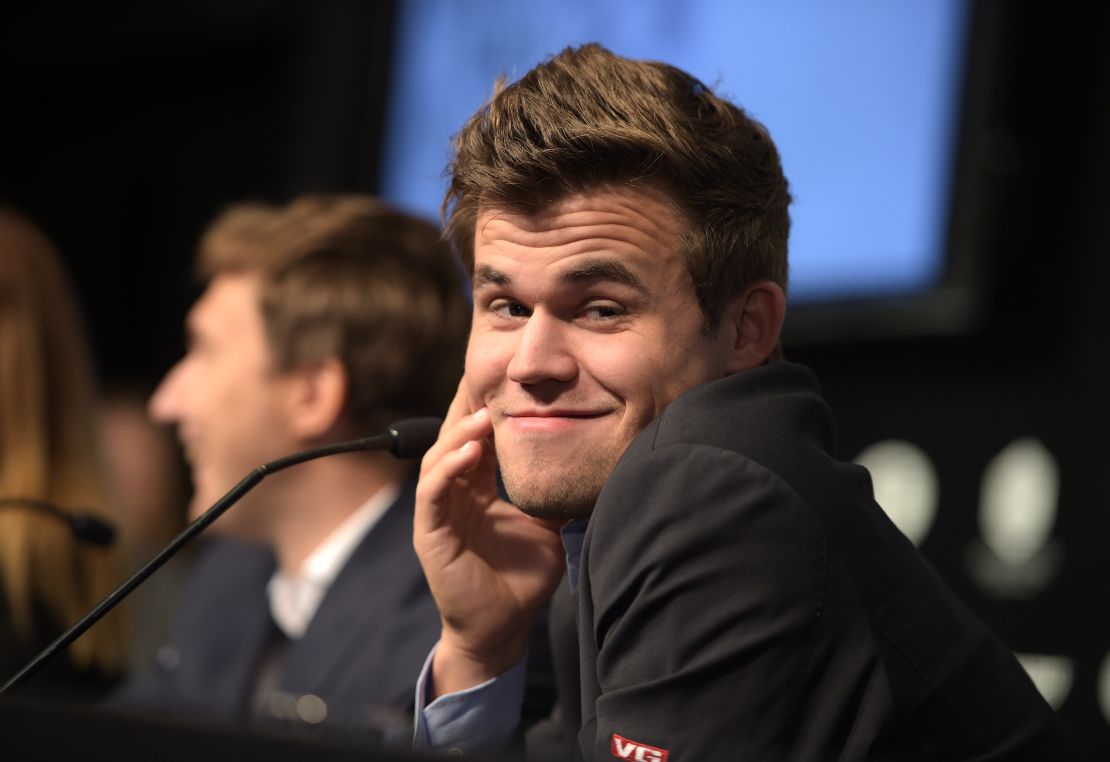

On one side of the board is reigning champion Magnus Carlsen, a 27-year-old Norwegian who, aged 14, was described by the Washington Post as the “Mozart of chess.” He models for G-Star, has endorsed Porsche, beaten Bill Gates in nine moves and 12 seconds, and is the highest-rated chess player in history. Forbes estimates his net worth at more than $8 million.

Aiming to topple one of the greats is challenger Fabiano Caruana – the first American to compete for the world title since Bobby Fischer in 1972. He is the world No.2 and is described as having superhuman powers of concentration. By the end of this month he could be world champion.

Chess has not been this fascinating since Fischer, the first western world champion in the modern era, took on Soviet Boris Spassky at the height of the Cold War in 1972 in what was seen as a clash of east versus west, a battle between capitalism and communism.

There has not been a match between players this closely ranked in almost three decades.

Visit cnn.com/sport for more news and videos

Caruana, one year Carlsen’s junior, has likened chess to MMA and boxing. Those who furrow their brow at such comparisons need only have watched the opening contests of this month’s 12-game title fight in the English capital to perhaps alter their perceptions.

The opening match lasted an agonizing seven hours before ending in a draw. The next day the evenly matched rivals faced up again. There is not much time for rest during 19 days of mental combat. In the second game it was Carlsen, in his own words, who was left to “beg for a draw.” Monday was a third straight tie of the showdown and on Tuesday there was no separating them either.

Four games down and deadlock – 2-2. The tension teeth-clenchingly high. Millions around the globe transfixed.

Under such pressure the pulse quickens, the mind whirrs, which is why Italian-American Caruana has made sure he is in peak mental and physical condition for the tournament. When time allows he will be pounding the treadmill between bouts and searching for Zen-like calm to soothe the mind.

“I have taken a liking to yoga recently, I’ve been practicing quite a lot. It’s important to try to counteract the negative, physical effects of chess – sitting down for so long under a lot of strain and mental stress,” says Caruana, speaking to CNN Sport last week on the eve of the championship.

Caruana is nerdy, but stylish, wearing a grey T-shirt and a bomber jacket made by the American designer Thom Browne for an afternoon of answering questions from journalists who have traveled to England from around the world. Though he left New York for Spain aged 12 and has not, he says, returned to the city where he spent much of his childhood for a while, his Brooklyn accent remains strong.

Focusing on the physical as well as the mental is not new for elite players, he says. The answer to the old argument of whether chess is a sport is irrelevant. Playing for such extensive periods takes its toll. After the “Moscow Marathon” between Anatoly Karpov and Garry Kasparov in 2000, which lasted five months and 48 games, Karpov told a Russian magazine he had lost 10kg in weight.

Carlsen is lithe and watches what he eats, while Caruana – who describes himself as a decent runner – is no different.

“When I was a kid I was encouraged by my parents to exercise and stay in shape. It was only more recently that I took it upon myself and became interested and really wanted to take care of myself,” says Caruana, who first played for the land of his Italian mother before switching allegiances to the US.

“I understood that chess can be physically demanding, although it doesn’t seem like it. When you’re under a lot of stress and your heart is racing and you’re just sitting down and there’s no outlet for it you really need to be in good shape to make sure it doesn’t get to your head.

“If you’re crashing at the board you won’t be able to play so I think pretty much all the top players these days are very aware of the necessity to be in good shape.

“I’ve tried to improve my cardio, I’ve done a lot of running and interval training to try to improve my cardiovascular system. I’ve had trainers in the past, but because I travel so much it’s kind of hard to have someone there to monitor what I’m doing so I also have to take it upon myself to make sure I know how to exercise and know what I need to do.”

It was an English journalist who described Caruana as having superhuman powers of concentration. The bespectacled New Yorker, who in 2007 became the youngest American-born grandmaster in history less than two weeks before his 15th birthday – a mark since beaten by Sam Sevian – laughs at such a description.

“At the board, I turn everything off and focus on that. I think that’s years of training, through playing and trying to not let mind wander,” he replies with a smile.

“As a kid, I found myself staring at the ceiling during a game and wouldn’t be thinking about chess at all, but through so many years of playing chess at a high level I’ve learnt to focus. I haven’t really had to consciously try to do it, it’s sort of just happened.”

The American was first introduced to chess aged five in an after-school program to help with his concentration. He lost all four of his first games, but quickly began to show promise by defeating older players and, in 2004, the family relocated to Spain so that the young prodigy could train with better instructors and play higher-quality opponents.

In admitting he was not enthusiastic about moving to Europe, the New Yorker chuckles: “When you’re 12 years old your parents don’t really ask you.”

Home-schooled in Spain, Caruana would practice for 10 hours a day on non-school days, but he does not regard it as a childhood lost.

“I wouldn’t say I’ve made any great sacrifices,” he says.

“When I was a teenager I guess I sacrificed on school and having the normal life of a teenager and having traditional education, but I’ve been quite fortunate. I haven’t had to make big sacrifices for my chess. I’ve had a relatively smooth road with the support of my parents to be able to devote myself to it.”

His parents reportedly estimate they spent as much as $50,000 a year paying for coaches and training before their son started making money in his late teens.

He will leave London considerably richer whatever happens in the final. There is a $677,000 prize for the winner, while the loser will walk away with $451, 000. And there’s sponsorship to boost the coffers, too. For Caruana, plans are afoot to launch a chess board line and apparel, while tech companies, sports brands and start-ups have shown interest in associating with the grandmaster.

In explaining the increasing interest in his client, Caruana’s manager Eric Kuhn tells CNN Sport that chess is at the “center of the zeitgeist” and that the players “represent everything that is now.”

During a press conference comprising about 200 representatives of the media, Caruana was asked last week how he would describe himself, being that he was playing “the Mozart of chess.” “My musical tastes lie more outside classical music, so I’d probably pick someone in the hip-hop or rock genre,” he said.

Both Caruana and Carlsen give chess a modern twist and their rivalry is the sort which elevates a contest to a wider audience. Some report that the pair aren’t fond of each other – In August, Carlsen made a shushing gesture when he played the American. With this world championship being so a close, all the elements are in place for a great spectacle.

The intuitive Carlsen, a grandmaster since 13, a world champion since 2013, is the favorite. But Caruana, described as a brilliant all-rounder, is on a hot streak, having beaten seven other top players to win the Candidates Tournament in Berlin in March. His official rating of 2,838 is just three points behind his opponent.

When asked whether he saw himself as the favorite or underdog, much to the amusement of the assembled journalists, a smiling Carlsen replied: “It has been a while since I have considered myself an underdog, to be honest. If you have been the No.1 ranked player in the world for seven years and have won three world titles in a row and consider yourself an underdog then there is something seriously wrong with your psyche, I think.”

But Caruana is a fighter. “I have the will to fight under any circumstances and it’s served me very well in the past to be able to fight from very bad conditions on the board, from the worst type of position, from a hopeless position, to try to fight back. That’s been my greatest strength,” he says.

Caruana also has belief. Asked if he thinks he can beat Carlsen, the American, regarded as the heir to Fischer, confidently replies: “I do think I’m going to win but it’s probably going to be really tough and harder than I realize.”