Editor’s Note: Maurice Hamilton is a Formula One author and journalist and has been covering the sport for more than four decades. He has attended more than 450 grands prix and written 19 books.

It’s been a thrilling Formula One season and as the 2018 campaign reaches its conclusion on Sunday at the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix, CNN Sport takes a look at some of the cars that have defined the sport over the years.

Maserati 250F

As race statistics go, the Maserati 250F barely makes an impression; just eight Grand Prix wins and a single drivers’ title between 1954 and 1959.

Aside from the constructors’ championship not being created until 1958, the paucity of results makes no difference to the 250F’s reputation as one of the finest and most graceful F1 cars ever built.

Having raced before and after World War II, the Italian firm produced the 250F to meet a change to 2.5-litre engines in Formula 1 for 1954.

READ: Robert Kubica returns to Formula One eight years after near-fatal crash

READ: Max Factor – Verstappen’s rise sparks Dutch adoration

From the moment it first appeared, the Maserati satisfied the ideal of what a Grand Prix car should look like; pure of line, the long, gently curved bodywork with its low snout finished off in a rich red, the Italian national racing color.

Not only was the 250F aesthetically satisfying, it was also a pleasure to drive. A finely balanced chassis allowed drivers to use the throttle as a means of powering the 250F through corners with the shapely tail hanging out.

The Argentine maestro, Juan Manuel Fangio, used the 250F to display his thrilling virtuosity as he won the 1957 world championship with ease.

Surviving examples change hands at auction for seven figure sums; an indication of arguably the most iconic F1 car of all time.

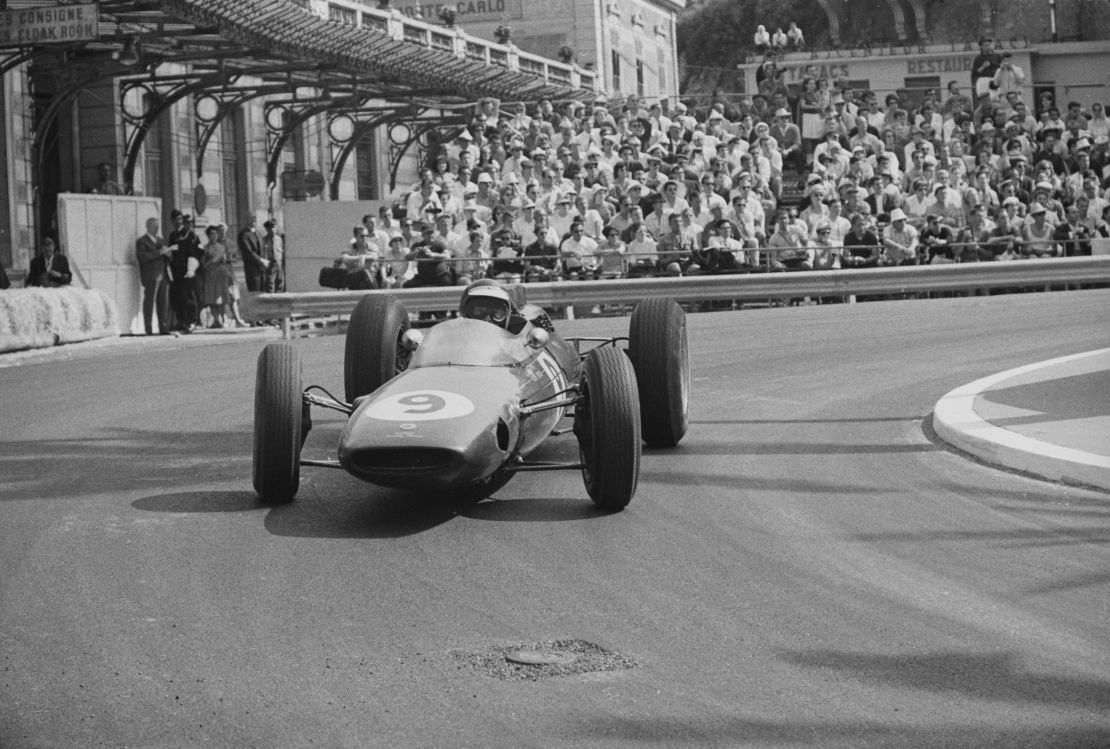

Lotus 25

Colin Chapman, the boss of Lotus and an engineering genius, revolutionized racing car construction by designing the monocoque chassis.

This fully stressed aluminum bathtub shape was three times stiffer and half the weight of the popular structure of welded tubes making up a so-called space frame chassis.

Introduced halfway through 1962, the Lotus 25 was instantly competitive and would have won the championship but for an engine failure at the final race.

Coupled with driving brilliance of Jim Clark, however, the Lotus 25 totally dominated the 1963 championship with seven wins.

The monocoque construction would become the standard for F1 design, spreading eventually to every racing formula.

Clark would also have won the 1964 world title but for an engine failure on the last lap of the final race – a development of the concept, the Lotus 33, easily took Clark to his second championship the following year.

A major change of formula for 1966 gave Chapman the opportunity to advance his thinking further with the Lotus 49 by attaching the engine directly to the monocoque (as opposed to supporting it in a separate frame).

The 49 went on to win the championship with Graham Hill in 1968 (the year Clark was killed in a Formula 2 race).

Brabham BT20

The Brabham BT20 (and its BT19 predecessor) is unusual among F1 engineering icons because of its relative simplicity.

Having won world championships driving for Cooper in 1959 and 1960, Jack Braham decided to run a team and build his own grand prix car.

Brabham had moderate success in 1964 and 1965 but a change of engine formula for 1966 provided the perfect opportunity for the wily and pragmatic Australian.

While major manufacturers such as Ferrari and BRM chose to build complex engines specifically for the new 3-litre formula, Brabham figured that a known and uncomplicated power unit would bring immediate results while rivals found their feet.

Accordingly, he took an American Oldsmobile V8 to Repco and had the Australian engineering firm develop what had been a production unit. It may not have been as powerful as some, but it was reliable.

Initially using a BT19 (almost identical to the BT20), Brabham won four grands prix to take his third title and become the first – and in all probability – the only man to win a championship in a car bearing his own name.

Brabham’s clever strategy continued when the Brabham-Repco BT24 of his team-mate, Denny Hulme, was good enough to win the 1967 world championship.

Lotus 72

The basic profile of F1 cars was altered forever in 1970 when Chapman produced the Lotus 72.

The most striking change involved side-mounted radiators, thus making way for a wedge shape, starting with a broad chisel nose. This optimized the car’s aerodynamics; a rich, new territory for F1 designers.

Unsatisfactory handling delayed the debut and prompted a major redesign of the suspension. Proof that a cure had been found came when Jochen Rindt won the car’s first grand prix in Holland.

Victories at three more races put Rindt in line for the championship but the Austrian was killed when a brake shaft snapped and sent the Lotus into the crash barrier during practice for the Italian Grand Prix.

Rindt would become the sport’s first posthumous world champion. Development of the Lotus 72 proved unsuccessful in 1971 but a further iteration brought Emerson Fittipaldi his first world title the following year.

Such was the fundamental sophistication of the car that continuing improvements ensured Lotus won the 1973 constructors’ championship, the drivers’ title being compromised by championship points split between Fittipaldi and Ronnie Peterson.

Amazingly, the Lotus 72 continued to be raced by the works team and privateers into 1975, five years after its conception.

McLaren M23

Reacting to a new rule in 1973 demanding F1 cars to have side-impact structures, McLaren chose to fully integrate these into the design rather than follow the popular trend of adding crushproof pads to the sides.

The resulting McLaren M23 had strength, simplicity and integrity throughout its wedge-shape design, although teething problems would affect the early races.

Three wins were no match for Tyrrell and Lotus in 1973 but the incorporation of lessons learned brought the drivers’ (Emerson Fittipaldi) and constructors’ titles with four victories the following year.

The M23 was substantially unaltered for 1975 when consistent finishes and three wins were not enough to beat the faster Ferraris.

McLaren continued to have faith in the design, reducing its weight and revising the suspension along with small but significant changes in readiness for 1976.

Fittipaldi’s eleventh hour departure left an opening for James Hunt, the Englishman seizing his chance with such a well-developed car.

Overcoming an early technical glitch, McLaren won six races during an epic season than ran to the wire, Hunt taking the title by a single point from Ferrari’s Niki Lauda.

The M23 had been developed through five specifications to ensure its front-line competitiveness across four seasons, making it one of F1’s most successful cars.

Lotus 79

Christened “Black Beauty” because of its elegant lines and black and gold colours, the Lotus 79 redefined F1 car design and performance. It was arguably the best of Chapman’s many flashes of genius.

Searching for another unexplored advantage, the head of Lotus applied his fertile mind to harnessing the passage of air through and under the car.

The initial concept was developed throughout 1977 with the Lotus 78, the unique feature being inverted wings hidden in the sidepods that helped suck the car to the ground.

Lotus won five grands prix that year and would have been in the championship reckoning but for a number of mainly engine-related failures.

Development was helped by a rare driver/engineer empathy between Chapman and Mario Andretti (similar to the relationship with Clark).

The product of their work was the Lotus 79, a car that would refine the so-called ground effect phenomenon from the moment it first appeared in 1978.

Backed up by Ronnie Peterson, Andretti became world champion, Lotus dominating the season with eight wins to walk off with the constructors’ championship.

It was to be the height of Chapman’s ambition – and the start of a terminal decline at Lotus as the next car, the 80, was a complete flop.

McLaren MP4/1

In September 1980, the ailing McLaren team was reformed to become McLaren International.

Technical director John Barnard, always searching for a new direction, was to make one of the biggest breakthroughs in F1 design when he abandoned the now traditional aluminium chassis in favour of one made from molded carbon fiber.

It was complex, but immensely strong and light – the two perpetual overarching aims in racing car design. Barnard also introduced a level precision and perfection hitherto unseen in racing car construction.

The McLaren MP4/1 made its debut in 1981, John Watson winning the British Grand Prix in the same year.

Watson and Niki Lauda used updated versions to win grands prix in 1982 and 1983 but the team’s competitiveness was being increasingly limited by the lack of a turbocharged engine to match those used by the competition.

Refining the same carbon fibre development, Barnard produced the MP4/2 to accept a bespoke TAG-Porsche turbo V6.

This car dominated 1984 with Lauda winning the drivers’ title by half a point from his team-mate Alain Prost in 1984, before Prost took his turn the following year.

Barnard moved to Ferrari but left behind a powerful legacy that would assist McLaren to further championships with the MP4/4.

Ferrari 640

Continuing his quest for substantial innovation following his move to Ferrari, Barnard thought long and hard about how to remove the bulky manual gear lever and rod running through the right-hand side of the cockpit to the gearbox mounted at the rear.

The idea of using a semi-automatic transmission was initially linked to a push-button gear selector on the steering wheel, Barnard eventually settling for paddles behind the wheel to work in tandem with a hydraulically operated clutch.

The associated reduction in cockpit dimensions allowed a narrow chassis, a sharp, slim nose and wide sidepods to house the radiators and maximise aerodynamic efficiency.

At first, the striking appearance of the red car was not matched by reliability, persistent problems with the gearbox delaying the first race until the start of 1989 rather than, as originally planned, during the previous season.

The Ferrari 640 (also known as the F1-89) was fast but no one expected it to finish, least of Nigel Mansell as he took the V12-powered car to a remarkable win on its debut in Brazil.

A failure to finish another race until mid-season wrote off any chance of the championship, but Barnard’s innovation would change F1 transmission design forever.

Williams FW14B

Williams had been working for some time on different avenues of F1 car development; semi-automatic gearboxes, traction control and active suspension.

They all came together in 1992 with the Williams FW14B, one of the most successful and arguably the most sophisticated F1 car of all time before regulatory control banned most of the complex systems involved.

The gearbox had been unreliable in 1991 but, once sorted, the driver could change gear four or five times faster without the risk of over-revving the engine.

Gradual work on active suspension – controlling the car’s ride height at a consistently efficient level – reached fruition with a switch from mechanical to a more effective electronic control, coupled with refinement of traction control.

The entire programme was overseen by technical director Patrick Head, who paid high tribute to the work of Adrian Newey as the designer packaged the multiple components into a workable and aerodynamically efficient form, coupled with a strong and powerful Renault V10 engine.

Mansell wrapped up the drivers’ championship five races before the end of the season thanks to a then record nine wins, Ricciardo Patrese’s victory in Japan and six second places helping Williams crush the opposition in the constructors’ championship.

Mercedes W05

Any major change in the technical rules represents opportunity. There was none bigger in recent times than the switch from normally aspirated to hybrid turbocharged power units for 2014.

Mercedes were better prepared than most for this substantial shift in F1 thinking.

Broadly speaking, in the past a team would receive the completed power plant from a manufacturer (possibly from within their own company), install it in the chassis and go racing.

Mercedes saw the need for detailed integration of the two, the entire package created to deal with the complex requirements of associated energy recovery and its application.

The programme and detailed planning were helped by the race team being 45 minutes down the road from Mercedes High Performance Powertrains in Brixworth, Northamptonshire.

And the final key factor was Lewis Hamilton making the bold decision to leave McLaren and align his future with Mercedes.

Six wins in succession (four for Hamilton and two for Nico Rosberg) at the start of the season set a standard that would continue, not just through 2014, but across five years as the Mercedes W05 template formed the basis for one the most dominant series of cars in the history of F1.