Two videos of two NFL stars in hotels physically attacking women, four years apart.

Some parallels exist – and if you were discussing the Kareem Hunt incident last week, the name of former Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice may have come up by way of comparing the two. After seeing the video of Hunt, Rice himself told NFL.com that “you look back at it and obviously you see some similarities between what happened in my situation.”

Both men were captured assaulting women on surveillance camera footage that probably would not have seen the light of day if celebrity gossip site TMZ had not released them. In both instances, the release of the videos led the league to implement disciplinary measures.

But experts in the fields of gender-based violence and sports say that’s largely where the similarities end.

The circumstances of the encounters were as different as the men’s relationships to the women. Rice knocked out his then fiancée in an elevator in an Atlantic City casino. Hunt said he had not previously met the woman who appears in the February 10 footage from a Cleveland hotel – and there’s still plenty we don’t know about Hunt’s situation.

Instead of getting mired in details, the conversation around Hunt should turn, they say, not to measuring him against Rice, but to bigger questions. Why is violent off-the-field behavior tolerated again and again? How often is it happening when it’s not caught on video? How can we prevent it?

Here’s what those informed observers say we should be talking about when we discuss former Kansas City Chiefs running back Kareem Hunt.

1. How and when the NFL reacts and acts

Hunt’s friend told police that the woman – who appears to be white – called them both a racist slur before the incident.

“It was just a disagreement, and I honestly wanted her just to leave,” Hunt told ESPN in an interview that aired two days after the video surfaced. “It’s no excuse for me to act that way or to even put myself in that position.”

The Kansas City Chiefs waived Hunt, their star running back, hours after the footage was published. The same day, the NFL placed him on the commissioner’s exempt list, meaning he cannot participate in football activities until the league completes its investigation.

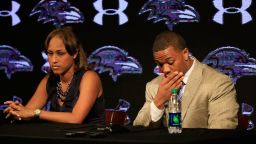

In 2014, two videos emerged of Rice assaulting his then-fiancée, now wife, Janay Palmer. Seven months after the assault, the Ravens released Rice and the NFL suspended him indefinitely.

“I’m not sure comparing the Rice and Kareem Hunt case is productive, but it is illustrative,” said USA Today columnist Kelly Whiteside, an assistant professor of sports media and journalism at Montclair State University in New Jersey. “Something bad happens, we react and then move on.”

“I would not be surprised if Hunt is playing in the NFL next year, given his age and talent. Winning, and the money that follows, means too much.”

After the NFL admitted to mishandling Rice’s case, they asked former FBI director Robert Mueller to look into what went wrong and offer the league recommendations for adjusting its discipline process. Mueller issued a 65-page report in January 2015 with a number of suggested improvements, including that the NFL more actively investigate when players are accused of domestic violence or violence against women.

Rice, who was reinstated by the NFL upon appeal, never played another down in the NFL after his initial suspension – in large part because of the incident, but also because his most productive years were behind him, Whiteside said.

Whiteside believes it’s more illuminating to compare what’s happening with Hunt to the case of Greg Hardy.

Hardy was convicted of assaulting a girlfriend, but then signed to a one-year $11 million contract with the Dallas Cowboys, she said.

“The Hardy case and the Hunt case show that off-the-field violence is tolerated, if an owner thinks that player can help the team win,” she said.

And since Rice, there have been several examples of professional athletes receiving lucrative contracts while charges are pending against them – one of them was just days before TMZ released the Hunt video.

The San Francisco 49ers released linebacker Reuben Foster the morning of November 25, hours after he was arrested on a domestic violence charge at a hotel in Tampa, Florida.

Two days later, the Washington Redskins claimed him off waivers, but he won’t immediately be taking the field. Like Hunt, Foster was placed on the commissioner’s exempt list while the league reviews his arrest on domestic violence charges.

“The Redskins fully understand the severity of the recent allegations made against Reuben,” Doug Williams, the team’s senior vice president of player personnel said in a statement. “If true, you can be sure these allegations are nothing our organization would ever condone.”

2. How video evidence seems to force action

Both cases do have one important thing in common: they reveal instances of violence that were hidden from the public eye – or at the very least, “not searched out diligently” by the NFL or the teams the athletes played for, said Michael Kasdan, director of special projects for The Good Men Project, which collects and publishes stories and research about modern masculinity.

“What if there was no video?” said author and activist Kevin Powell. “Would we be having this conversation right now? No, I don’t think so.”

TMZ released video on February 19, 2014, showing Rice dragging an apparently unconscious woman from an elevator four days earlier. After the early-morning fight, the two were arrested and each was charged with simple assault.

One month later, Rice was indicted on a charge of aggravated assault and the charge against Palmer was dropped. The couple married the next day, on March 28.

Rice pleaded not guilty in May and entered a pretrial intervention program for first-time offenders that would clear him of charges in one year. Amid criticism that the punishments from the NFL and criminal justice system were too light, Rice received a two-game suspension and a fine in July 2014.

More outrage followed when, in September 2014, TMZ released video from inside the elevator showing Rice knocking Palmer to the ground. The same day, the Baltimore Ravens released him and the NFL and suspended him indefinitely – seven months after the incident.

Even before the second video came out, though, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell admitted that the two-game suspension was too lenient and created a discipline standard: Any players who violated the league’s personal conduct policy regarding assault, battery, domestic violence or sexual assault with physical force would be suspended six games for a first offense. Despite its discipline policy, the NFL has not held fast to that six-game standard in several incidents of violence against women.

With Hunt, the league and Cleveland police have provided conflicting responses regarding when the league first received or reviewed police reports or the surveillance footage.

The league said it began investigating immediately after the altercation. No arrests were made as a result of the incident and Hunt has not been charged with a crime, according to Cleveland Police.

A police spokesperson said the league didn’t make a formal request for police records or the surveillance video until November 30, the same day TMZ published the surveillance video. An NFL spokesperson disputed the Cleveland Police statement, noting they “had multiple verbal conversations with Cleveland police officers and requested surveillance video immediately upon learning of the incident in February.”

The league said it was unable to get access to the hotel video and was not able to speak with the complainants in the hotel fight. Hunt told ESPN the league did not interview him – but he admitted to lying about the incident to the Chiefs.

When the video surfaced on November 30 through TMZ, the consequences were swift. Now, Hunt is on the defensive as he has been accused of two more violent acts – before and after the Cleveland incident.

An agent representing Hunt did not respond to a CNN request for comment.

3. The larger issue of violence against women

Violence against women is not just an NFL problem, it’s a societal problem, Whiteside points out.

“In many ways, sports are this nation’s front porch,” she said, pointing to how the Rice video put the issue of domestic violence in the headlines.

But when these incidents thrust the issue of off-the-field violence into the spotlight, we have an opportunity for a national reckoning, she said – and that opportunity is too often squandered.

“The discussion of difficult issues in sports raises the public’s consciousness even if a significant portion of America wants its athletes to shut up and dribble … or tackle.”

Sports fans might be tempted to look at high-profile cases of off-the-field violence and rank them in comparison to each other. After all, that’s how the criminal justice system works: it evaluates the severity of a crime and assigns punishment based on numerous factors, including the nature of the offense and the offender, including his background, likelihood of reoffending and amenability to treatment.

But when it comes to empathizing with victims, the same sliding scale should not apply, said Powell, author of “The Education of Kevin Powell: A Boy’s Journey Into Manhood.”

“It’s all bad,” he said of the incidents involving Rice and Hunt. “They’re both women and both human beings, no matter their relationship to them.”

4. What might cause men to be violent

Violence against another person is never excusable, said Lisa Hickey, publisher of The Good Men Project and CEO of Good Men Media Inc.

But violence does not occur in a vacuum, and it’s important to understand how popular culture and society minimizes and normalizes abuse, including in sports, she said.

“The NFL looks for players who are aggressive – and, by definition, that means they have to be OK with harming themselves and others,” Hickey said.

While we don’t know how much this is the case in Rice or Hunt’s private lives, it’s clear football is a violent sport. Research shows that the repeated blows athletes experience can cause brain damage that may develop into Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), which may lead to behaviors such as increased aggression, risk-taking, and loss of executive function, she said.

Systemic racism is also a form of abuse, Hickey said. Using the n-word is a form of racial violence, although “we, as a society, have failed to understand the implications of repetitive racial violence over time and the trauma it causes.”

“Players are also coached to be violent, and then are expected to turn off the violence when they leave the field. The cycle of violence escalates and then we are surprised when violence spills off the field and into other areas,” Hickey said.

“One of those areas it often spills to is violence against women – and violence against women is normalized in our society to such an extent that not only do we fail to do enough to prevent it – we often don’t even see it until there is a video as extreme as the ones with Kareem Hunt or Ray Rice,” she said.

Research shows that, oftentimes, people who are violent were themselves victims of abuse, and it can influence their behavior. Powell says he knows this firsthand as someone who experienced childhood violence and went on to become physically violent toward others, including one instance in which he pushed a girlfriend. His life experiences inform his current work as a speaker and mentor who visits schools and workplaces to discuss toxic masculinity.

“You can’t keep getting in trouble and think there’s no problem,” he said. “You have to be the person to defuse the situation. You have to walk away.”

He points to reports that one month before the Cleveland incident, Hunt was accused in a nightclub brawl in Kansas City, Missouri. The altercation involved six to eight others that left a man with a broken nose and rib, according to police. Three months later, he reportedly punched another man in the face at an Ohio resort. Neither incident led to criminal charges.

“There’s something very jarring about that, when someone’s constantly getting in trouble,” Powell said. “You have to ask, ‘what’s going on? Why is no one intervening here? You need to get some help.’”

Rice told a reporter for NFL’s website that he’d be happy to talk to Hunt about what he’d learned since his suspension.

“I’m never going to call myself an expert. I’ve discussed the remorse I have for survivors of domestic violence,” he said, “but knowing what I know now, the top priority is learning that it comes down to those split-second decisions, which come at the most hostile times. And that’s where this could be a teaching tool.”

Correction: This article has been updated to correct a reference made to Kevin Powell and his past experiences. Powell told CNN he experienced childhood violence and physically abused a partner in the past. The article has been corrected to accurately describe what he said.

CNN’s Eric Levenson, Elizabeth Joseph and Marlena Baldacci contributed to this report.