Hearts thumping under thin race suits, eyes wide beneath goggles, they edge their skis under the starting wand and let out one big, final breath.

Below, the hard, icy track, smeared blue by the course markings, plunges away. In the distance, on a clear day, the Kitzbuheler Horn pierces the Austrian sky. The ancient spires and roofs of historic Kitzbuhel nestle in the valley.

But these helmeted daredevils can only focus on the first few feet of the beckoning course – a sharp right and left turn, and then the lip of the infamous Mausfalle jump, an elevator drop of 60 meters. When they explode from the gate, they’ll rocket from 0-60mph in about three seconds.

Kitzbuhel’s revered downhill, raced on a snaking, tree-lined ribbon of sheet ice known as the Streif off the Hahnenkamm peak above town is ski racing at its most raw.

READ: Why even Arnold Schwarzenegger can’t resist skiing’s bucket-list party

Wengen’s classic Lauberhorn downhill might be longer and clock a faster top speed, but for sheer pedal-to-the-metal rock ‘n’ roll racing, Kitzbuhel is the one.

The danger, drama and derring-do attracts tens of thousands of fans for the biggest cow bell-clanging, schnapps-infused party in the Alps with the A-list regularly headed up by Austrian megastar Arnold Schwarzenegger. And this year marks the 80th anniversary of the legend race.

“It’s skiing at its best, skiing on the edge, the ultimate test of a ski racer,” said 1980 champion Ken Read of Canada, recalling his glory days to CNN while gazing back up the course in 2019.

“The Streif is without question the most challenging downhill in the world.”

Visit CNN.com/Sport for more news, features and video

Suppress fear

Launching off the Mausfalle, racers are fully committed and swoop quickly towards the Karusell, a tight right hander where forces of 3G are generated on the body. Next up the Steilhang, a slick, bumpy, steep wall followed by a narrow right-hand exit with two rows of safety nets beckoning those who overcook it.

American Bode Miller did once, but rode the netting on two skis and raced on. The features come quickly, the names dripping with legend built up over the years since the Kitzbuheler Ski Club (KSC) organized the first race in 1931.

“You have 35 seconds of absolutely the most intense ski racing you can imagine,” adds Read. “No other downhill has such a long, intense period with one thing after another. You have no time to think, you just do it.”

Austrian great Franz Klammer, who won the race four times, likened it to “jumping into cold water without knowing how to swim.”

The ability to suppress fear and bury bad thoughts is key at Kitzbuhel. Some embrace the challenge and attack it, others are overwhelmed by it.

“My first time I braked twice before the Mausefalle,” two-time champion Dominik Paris told CNN’s Alpine Edge.

Only once you’re in a settled tuck position on the gliding Bruckenschuss can you take brief stock.

READ: How getting fit to ski can help tap into your sixth sense

READ: How to hit 100mph in skiing’s oldest, longest, fastest race

Guts for glory

Read, who was one of the group of pioneering Canadian racers known as the “Crazy Canucks,” faced fear head on at Kitzbuhel and scored three thirds to go with his victory.

“For me fear was never a factor,” adds Read, who won in Wengen the week after his Hahnenkamm heroics. “Nervousness, yes, because you’re pushing yourself to the limit and it’s a competition and you want to pull out an exceptional performance.”

His face lights up: “For me it was the most exciting thing one could imagine. For a young downhiller it was like being let loose in a candy shop.”

Klammer, the 1976 Olympic champion, says the defining features of a great downhiller are “guts” and the willingness to “take a risk.”

“Downhill racing is freedom,” he told CNN. “That’s the special part, so you have to be ready, even though it’s very risky, and go for it.”

READ: How Special Forces training is speeding up US ski team

Kitzbuhel: Former silver mining town to Tyrolean treasure and ski racing mecca

But Klammer insists it’s not all about brazen bravado. The Streif has a number of gliding sections in which aerodynamic position, feel for your skis and carrying your speed are a”big part” of being successful, he says.

The midway point of the course is the fall away jump above the Seidlalm chalet, but the cruising straight of the Larchenschuss below offers only brief respite before racers have to think about the perils of the Hausberg jump.

“The fatigue factor is starting to come in, but not so much physical as mental because you’ve been so on it and so focused,” says Read, who like all winners has his name on one of the Hahnenkamm gondola cabins.

Into the red room

Taking air off the Hausbergkante, the racers must land and quickly absorb a compression before standing hard on the right ski to make a left turn.

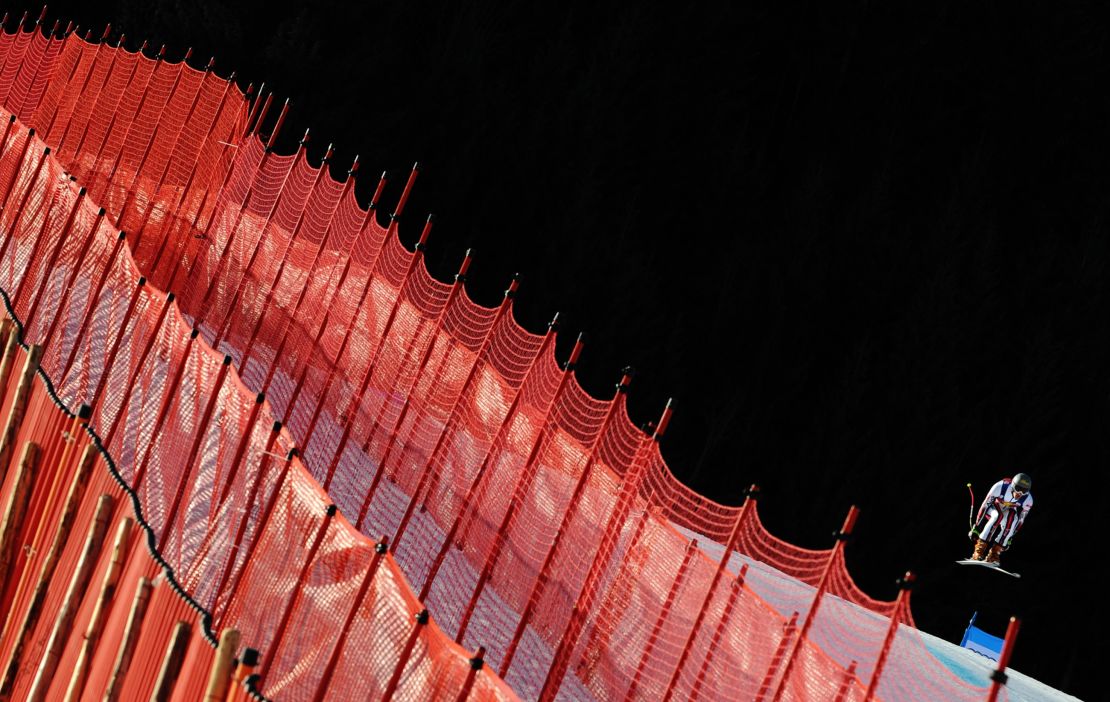

But the Hausberg has caught out some of the biggest names in skiing over the years. In 2016 Aksel Lund Svindal and Hannes Reichelt both suffered spectacular crashes and ended up tangled in the “red room,” as the safety nets are called. For Svindal, the current Olympic champion, it was season over.

“Coming over Hausberg, all hell is breaking loose,” adds Read. “You’re dropping, accelerating, going through a compression turn and into another blind turn where you have to be on line to come across the traverse and into the finish.”

After the bouncing, chattering, icy traverse which tries with all its might to pull you downhill and off line, there’s a final sting in the tail with the Zielsprung, a vicious, high-speed jump into the finish.

It nearly cost Swiss racer Daniel Albrecht his life when he landed on his back and catapulted onto his front in 2009. He was placed in a coma but recovered to race again in December 2010.

Those still on their feet are enveloped into the finish area by a pulsating mass of cheering, beer-swilling, flag-waving fans, pumping beats, a riot of color, noise and smells. For some of the roaring fans the legendary race is an annual fixture on the social calendar, for others a cherished one-off pilgrimage.

“I had to see the race live,” says Norwegian Sture Norevik, clutching a plastic cup of beer. “It’s one of those things I wanted to feel live – not sitting back home on my sofa.”

The party is in full swing and will continue long into the night on Kitzbuhel’s cobbled streets.

For Paris, winning for the first time at Kitzbuhel was “the greatest day of my life.” Last year, he clinched his third Hahnenkamm title. “I’ve no words to describe this emotion, it’s very special,” he told reporters. “It’s not normal to win on this hill three times. It’s just amazing.”

Paris injured his knee in training this year and is out for the season, offering a better chance for someone else to carve their name in legend.

“When you cross the finish line and you the have good fortune of being in first place and you hear the reaction of about 40,000 people screaming and yelling, it’s the best moment in sport,” says Read.

“If you’re Austrian, you’re God.”