You’ve probably heard of identical and fraternal twins, but a report published Thursday says there’s a third kind – sesquizygous twins or “semi-identical.”

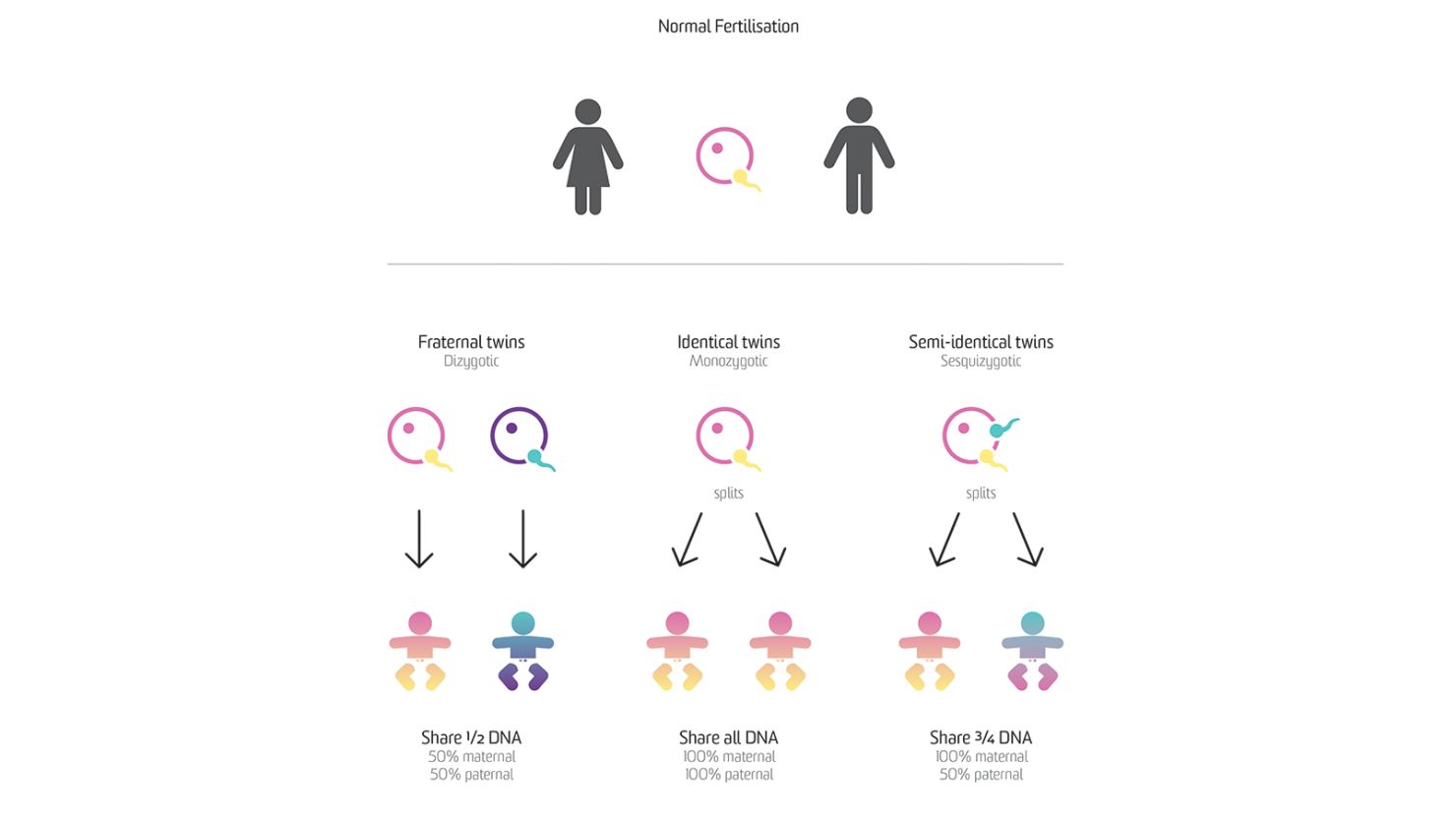

Identical – or monozygotic – twins pop up from a single fertilized egg that eventually splits in two and forms two identical boys or two girls. They share 100% of their DNA.

Fraternal – or dizygotic – twins form from two eggs that have been fertilized by two of the father’s sperm, producing two genetically unique siblings. They share 50% of their DNA.

But “semi-identical” twins are so rare, experts say they have only identified two cases – ever.

Right along that DNA-sharing spectrum, “semi-identical” twins share anywhere from 50% to 100% of their genomes, researchers say.

And they’re extremely, extremely rare. The only other reported case of sesquizygotic twins was reported in the United States in 2007. The recently identified twins from South East Queensland are now 4 years old and healthy.

Details of this second case were published this week in the New England Journal of Medicine. Researchers from the University of New South Wales and the Queensland University of Technology combed through nearly 1,000 cases of twins to confirm their findings.

How were they discovered?

Authors of the study were observing a 28-year-old woman’s pregnancy in 2014 when they noticed her set of twins shared a placenta, appearing to be identical twins.

But the 14-week ultrasound showed they were different genders – making it impossible for them to be monozygotic twins.

These twins were formed when a single egg was fertilized by two sperm – something that shouldn’t happen, Dr. Nicholas Fisk, who participated in the study and serves as the deputy vice chancellor of research at the University of New South Wales, told CNN.

That’s because, he said, once a sperm enters the egg, the egg locks down in order to prevent another sperm – from the thousands swimming around – from entering.

“Even if two got in, an embryo with three rather than the normal two sets of chromosomes won’t survive as a fetus,” he said.

But in this case, Fisk said, when the egg was fertilized by two sperm, it split the three sets of chromosomes into two separate cell sets, thus forming the twins.

“Some of the cells contain the chromosomes from the first sperm while the remaining cells contain chromosomes from the second sperm, resulting in the twins sharing only a proportion rather than 100% of the same paternal DNA,” clinical geneticist Dr. Michael Gabbett, who worked with Fisk, says.

The Australian twins share 89% of their DNA.

How can we be sure?

After their discovery, researchers questioned whether sesquizygotic twins had just been going underreported, or wrongly identified as fraternal twins. So they looked at 968 dizygotic twins to make sure this wasn’t the case.

“We needed to confirm the results with really exhaustive studies in multiple labs (in multiple states/countries), and with tests involving millions of genetic variants,” Fisk said.

So it’s safe to say, they’re sure.

“The paper took two years from submission to publication, as we needed to convince rightly skeptical reviewers that this really was robust,” he said.