At first, she just forgot a name or two. Then, a few meetings on her schedule. A few months later, LuPita Gutierrez-Parker found herself struggling at work to use computer software she knew intimately.

“In the beginning, when I wasn’t sure what was happening to me, I just figured it must be stress because I was doing a lot of work and had too much on my mind,” Gutierrez-Parker said.

Another few months passed, and she found herself re-reading the same passage in documents to comprehend their meaning. When her command of language also began to fail, Gutierrez-Parker, who lives in Yakima, Washington, began to worry.

“Why did I just say that? That’s not grammatically correct,” she would think. ” ‘That wasn’t me. I have a very strong vocabulary.’ I was avery articulate person.”

Yet it took her another year or so to bring up the topic with her primary care physician.

The delay in seeking answers to cognitive decline is not surprising, according to a survey included in the Alzheimer’s Association’s 2019 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures report, released Tuesday.

“We need to increase the confidence and the skills of front-line providers so they can provide more care in this area,” said Joanne Pike, chief program officer at the Alzheimer’s Association.

“And we need to destigmatize the process for seniors, encouraging people to talk to their health-care providers and families about their concerns,” she said.

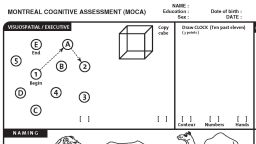

Gutierrez-Parker’s primary care doctor gave her a mini-cognitive assessment, asking her some question verbally and then on paper. It didn’t go well.

“I said, ‘what did I flunk?’ ” Gutierrez-Parker remembered. “And we both laughed because she knew I was an educated woman.”

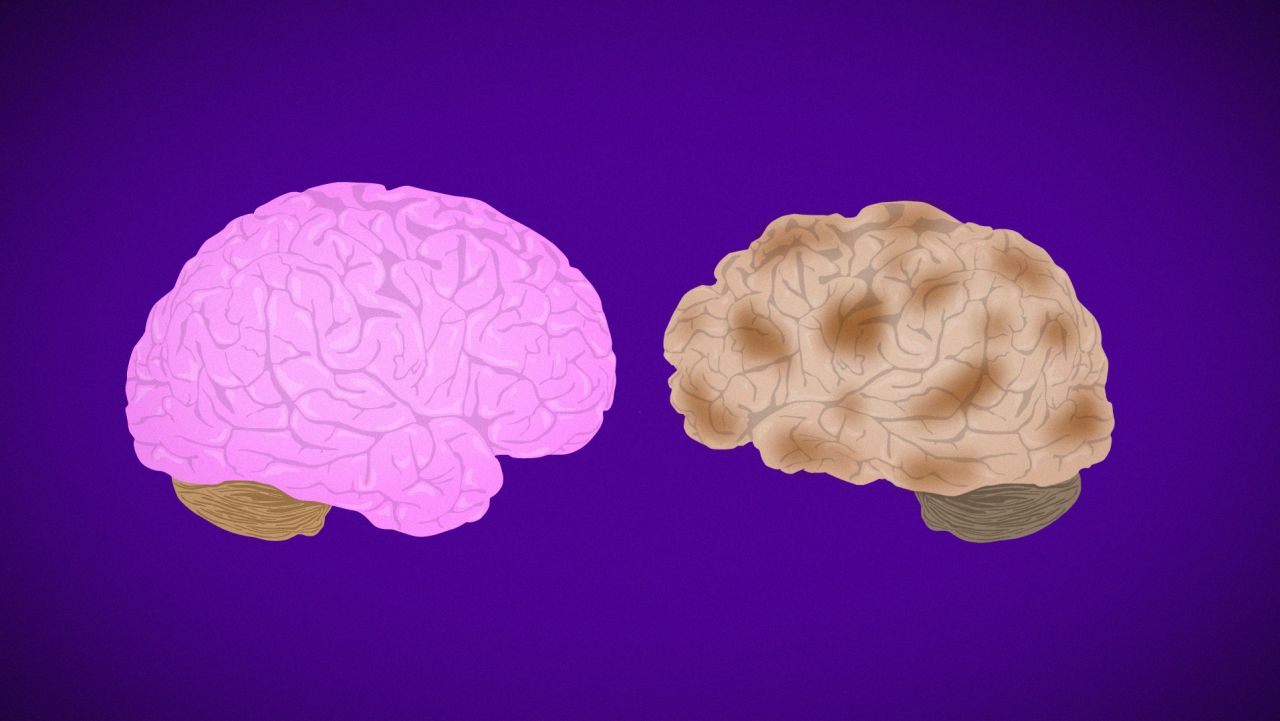

A PET scan and neuropsychological evaluation six months later confirmed her worst fears. In 2016, at the relativelyyoung age of 61, Gutierrez-Parker was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, an early stage of dementia.

Even though she was devastated, she also “felt reassured knowing that they finally put a label on what was wrong with me” and encourages others who are worried about their mental status to reach out to a doctor for help.

A call to action

The Alzheimer’s Association couldn’t agree more. In its annual report, the association includes a call for action to the nation’s primary care physicians. Every senior should receive a brief cognitive assessment at their first Medicare annual wellness visit at age 65, the group says, and the exams should be a regular part of their ongoing annual care.

Yet a survey by the association found that early cognitive assessments were not the norm during most senior doctor visits.

“The survey found a really troubling underuse of cognitive assessments during the annual healthcare checkup,” said Pike. “Despite a strong belief among seniors and physicians that cognitive assessments are important for the early detection of Alzheimer’s, only half of the seniors in the survey were being assessed for cognitive decline. And only 16% [of] seniors received regular followup assessments.”

A comparison of those statistics against those of other wellness checkup items give a clear picture of the disparity, Pike said. In each visit, physicians check cholesterol 83% of the time, vaccinations 80% and blood pressure 91% of the time, she said.

“So while physicians say it’s important to assess all patients age 65 or older, fewer than half are saying that it’s part of their standard protocol,” she said.

A good bit of that might be due to “a strong disconnect between seniors and doctors as to who should initiate the conversation,” Pike said. Over 90% of seniors thought their doctor would recommend testing, so fewer than 1 in 7 brought the topic up on their own, the survey found. Primary care physicians, on the other hand, say they are waiting for senior patients and their families to report symptoms and ask for an assessment.

“We need to increase the confidence and the skills of front-line providers so they can provide more care in this area,” Pike said. “And we need to destigmatize the process for seniors, encouraging people to talk to their health-care providers and families about their concerns.”

Gutierrez-Parker agrees. She’s thankful she has the chance to spend quality time with her family, and volunteer for the Alzheimer’s Association to bring awareness to her community.

“I would say to people who have an opportunity to find out what is wrong with them, to do it,” she said. “It gives you more opportunities to get your house in order: do advance directives, your will, even your funeral. It’s peace of mind, and it takes that load off your family.

“Get it done and then enjoy the rest of your time with your family and loved ones.”

Prevalence of Alzheimer’s

There’s a bit of good news buried in the association’s annual report. A flurry of recent studies show that Alzheimer’s and other dementias in the United States and other higher-income Western countries is on a decline, mostly due to tighter control of cardiovascular risk factors and improved education. But overall, study results are mixed and inconclusive, according to the report, and certainly will have little effect on the current rise in cases in the United States as the baby boomer population continues to age.

With no significant treatment and no cure in sight, the association’s report projects that by 2025, the number of Americans 65 and older with Alzheimer’s will “reach 7.1 million – almost a 27 percent increase from the 5.6 million age 65 and older affected in 2019.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

It’s the “oldest old,” those over 85, who are most at risk for Alzheimer’s, the association says. In 2019, there are just over 2 millionAmericans 85 and older; in 2031, when the first wave of baby boomers hits that age, the number will rise to 3 million. By midcentury, there will be 7 million of the “oldest old” in the United States, accounting for half of all people over 65 with Alzheimer’s.

The cost to society will be substantial, the report says. In 2019 alone, it estimates a $290 billion burden from health care, long-term case and hospice combined. Medicare and Medicaid will cover $195 billion of that, with out-of-pocket costs to caregivers reaching $63 billion.