Adapted from “The Chief: The Life and Turbulent Times of Chief Justice John Roberts” by Joan Biskupic. Copyright ? 2019. Available from Basic Books.

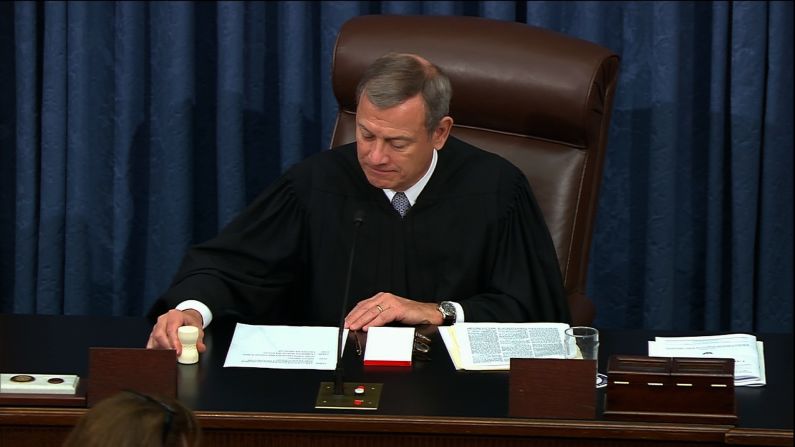

Now that he holds the decisive vote at the center of the US Supreme Court, Chief Justice John Roberts has been moderating positions as he tries to ensure the court does not lunge too far to the right. But there is one area of the law where he is likely to remain uncompromising: race.

“The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” Roberts has insisted, expressing a view that can be documented back to his service in the Ronald Reagan administration in the early 1980s.

His opinion arises from fundamental notions of how individuals succeed in America and reflects his personal experience and understanding of the Constitution.

Government remedies tied to race, whether public school integration plans or university affirmative action, Roberts believes, instead hurt African-Americans, Latinos and other racial minorities.

When Justice Sonia Sotomayor referred in a 2014 case to racial minorities who may think, “I do not belong here,” Roberts responded: “Racial preferences may themselves have the debilitating effect of reinforcing precisely that doubt.”

Roberts’ views, while generating tension with his colleagues, have made a significant difference in the law, particularly in narrowing protections for voting rights. That pattern is likely to continue as the Supreme Court revisits election rules and redistricting, as well as university affirmative action. A case challenging Harvard’s racial admissions policy could soon be headed its way.

The court last week heard a racial gerrymandering dispute from Virginia and, on Tuesday, a related partisan gerrymandering question in cases from Maryland and North Carolina. Additional voting disputes are moving through lower courts toward the justices, including over state voter-identification rules, restrictions on absentee ballots and new limits on voting times.

Other crosscurrents have developed on the nine-member bench: While Roberts has occupied the decisive position along the ideological spectrum since Justice Anthony Kennedy retired, he is a more consistent conservative than Kennedy ever was. Kennedy, for example, became open to racial affirmative action with time, voting in 2016 to uphold a program at the University of Texas at Austin.

Roberts has an institutional interest in ensuring that the court not swing too far to the right and he has already signaled that he might be trying to broker consensus across the ideological divide. But that probably will not happen with the difficult issue of race, where his views are entrenched.

RELATED: The inside story of how John Roberts negotiated to save Obamacare

Racial discord of the day

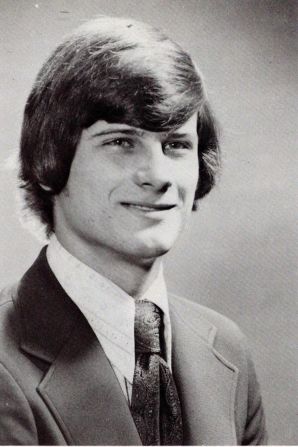

Roberts, now 64 and in his 14th year as chief justice, came of age during the civil rights unrest of the 1960s and ’70s. He grew up in the onetime vacation community of Long Beach, Indiana, about 60 miles from Chicago. He was 13 when riots erupted there after Martin Luther King Jr.’s April 4, 1968, assassination.

But he was insulated from urban strife and other racial discord of the day, living in a nearly all-white community and attending an elite boarding school close to his home.

Roberts’ father was an executive at a Bethlehem Steel plant, witnessing racial tensions growing from the federal government’s efforts to end discrimination after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The Department of Justice targeted major steel companies as well as the United Steelworkers of America, alleging that they conspired to keep blacks in low-level jobs in the mills. A series of lawsuits led to court-supervised pacts under which racial minorities advanced to better jobs.

Roberts’ life in northern Indiana has shaped his outlook.

At the La Lumiere boarding school, amid close-knit, enduring friends, Roberts later said, he learned the value of persistence.

“No quality is more essential to achieving your hopes for the future,” he told the school’s graduates in 2013. “And unlike many other keys to success – intellect, talent, physical ability, health, looks, where you were born, into what sort of family, luck – persistence is entirely, entirely within your control.”

“The slogan ‘press on’ has solved and will always solve the problems of the human race,” maintained Roberts, who has demonstrated persistence yet was fortunate to have started with other advantages too.

When he graduated in 1973, Roberts was first in his class and La Lumiere’s first Harvard-bound graduate.

Debate over affirmative action – related to student admissions, as well as faculty and staff positions – was roiling Harvard’s campus in the 1970s when he was there. Roberts was not politically active at the time and later said he was turned off by some of the liberalism of the era.

On the national level, the case of Allan Bakke, a 35-year-old white man twice rejected for admission to the University of California at Davis medical school, was moving toward the Supreme Court. That led to the 1978 decision in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, allowing schools to consider race as a factor in admissions but disallowing quotas.

Roberts graduated from Harvard Law School in 1979 and after two judicial clerkships, one for Justice William Rehnquist, began working for Reagan. Documents from those days reveal him to be an aggressive lieutenant for the Republican administration’s efforts to narrow the reach of federal voting rights law and racial remedies.

“This is an exciting time to be at the Justice Department, when so much that has been taken for granted for so long is being seriously reconsidered,” he wrote to Judge Henry Friendly, for whom he had worked before serving as a law clerk to Rehnquist.

Roberts’ memos show that he was often trying to drive the conversation. He was ready to admonish colleagues whom he believed insufficiently committed to the Reagan agenda. Even in his early months in the Department of Justice, he alerted the attorney general to what he believed were inconsistencies in agency practices related to the administration’s new “colorblind” racial policies.

It was in this period that Roberts solidified his view that remedies tied to an individual’s race could be as repellant as racial discrimination in the first instance.

Later, when Roberts was a deputy solicitor general in the George H.W. Bush administration, he developed arguments against school district integration plans and government preference policies for blacks, Hispanics and other minorities. He rejected group-based remedies and believed that individuals who faced bias should be able to sue only for specific instances of discrimination.

“Racial balancing,” as he termed practices that gave preference to blacks and Hispanics to offset past discrimination, was unconstitutional, he believed, even when carried out in the name of diversity.

View of Brown v. Board of Education

Within a year of his appointment as chief justice, Roberts was voicing analogous sentiment. “It is a sordid business, this divvying us up by race,” he wrote in a 2006 voting rights case.

The following year, he elaborated on his views of race in a dispute over school integration involving Louisville and Seattle schools. The paired cases arose from attempts by school districts to counteract the return of school segregation caused by whites and blacks living in separate parts of a city.

Roberts voted to strike down the plans, voicing a clear, if controversial, idea about what the Supreme Court had intended in Brown v. Board of Education. He said the 1954 landmark ruling, invalidating the separate but equal doctrine, extended to any program separating children on the basis of race, including for integration.

Before “Brown, schoolchildren were told where they could and could not go to school based on the color of their skin,” Roberts wrote. “The school districts in these cases have not carried the heavy burden of demonstrating that we should allow this once again – even for very different reasons.”

In that case, and a later one involving affirmative action at the University of Texas at Austin, Roberts questioned the value of diversity in the classroom.

Kennedy, who separated himself from Roberts on this point, believed diversity could be a compelling governmental goal. In the Louisville and Seattle disputes, Kennedy said no proof had been offered that the racial classifications were the only way to achieve that diversity. He voted to invalidate the district programs but without adopting Roberts’ rationale. (The four dissenting justices – all liberals – argued that the two school districts had offered sufficient grounds for the integration plans.)

“Fifty years of experience since Brown v. Board of Education should teach us that the problem before us defies so easy a solution,” Kennedy wrote. “The enduring hope is that race should not matter; the reality is that too often it does.”

Kennedy was among the justices over the years who have challenged Roberts’ approach as impractical in a country still rife with racial divisions.

Voting Rights Act

Roberts more fully revealed his thinking on race in the 2013 case of Shelby County v. Holder curtailing the reach of the milestone 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The dispute arising from Shelby County, Alabama, has been Roberts’ most consequential decision on race to date, forbidding federal officials from screening potentially discriminatory voting rules from states like Alabama with histories of racial bias.

President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act in August 1965 as civil rights demonstrations and police violence plagued the South. One of the most troubling events that forced passage of the law had occurred on March 7, 1965, at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. In what became known as Bloody Sunday, Alabama state troopers wielding clubs and bullwhips had attacked some 600 activists who were marching slowly and silently through the streets of Selma.

The new law addressed discrimination in two main ways: by permitting lawsuits against direct government bias in election practices and by requiring certain states and localities to obtain federal approval before instituting new election procedures.

That latter “preclearance” provision, deriving from a formula that dated to the 1960s, was disputed in the 2013 Shelby County case. Writing for the majority, Roberts said the provision was outdated.

“Our country has changed,” he argued, “and while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions.”

In photos: Chief Justice John Roberts

His ruling echoed views from his early legal career, when as a Reagan administration lawyer he believed federal voting-rights law excessively interfered with activities that the states should be able to regulate.

Roberts concluded that problems the Voting Rights Act was designed to correct no longer existed.

“In 1965, the States could be divided into two groups: those with a recent history of voting tests and low voter registration and turnout, and those without those characteristics,” he wrote in Shelby County. “Today, the Nation is no longer divided along those lines, yet the Voting Rights Act continues to treat it as if it were.”

Senior liberal Justice Ginsburg wrote for the dissenters. Her 37-page opinion (13 pages longer than Roberts’ for the majority) was so passionate that it spurred the “Notorious RBG” meme on the internet, a play on the late rapper Notorious B.I.G.

“The sad irony of today’s decision lies in its utter failure to grasp why the VRA has proven effective,” Ginsburg wrote. “The Court appears to believe that the VRA’s success in eliminating the specific devices extant in 1965 means that preclearance is no longer needed. … In truth, the evolution of voting discrimination into more subtle second-generation barriers is powerful evidence that a remedy as effective as preclearance remains vital to protect minority voting rights and prevent backsliding.”

Joined by the three other liberals, Ginsburg wrote that “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

The chief justice invoked a different metaphor as he criticized Ginsburg and the other dissenters for pointing to contemporary race discrimination in Alabama.

“The dissent … turns to the record to argue that, in light of voting discrimination in Shelby County, the country cannot complain about the provisions that subject it to preclearance,” Roberts observed. “But that is like saying that a driver pulled over pursuant to a policy of stopping all redheads cannot complain about that policy, if it turns out his license has expired. Shelby County’s claim is that the coverage formula here is unconstitutional in all its applications.”

The conservative-liberal angst on voting is likely to go on as Voting Rights Act disputes continue nationwide. This month, the justices heard a racial gerrymandering case from Virginia in which challengers said black voters were concentrated into districts, diluting their electoral influence.

The justices also are airing two partisan gerrymandering cases, from Maryland and North Carolina. Partisan gerrymanders, which often accompany racial ones, are thornier in the legal realm because while racial bias in redistricting is outright unlawful (racial minorities are specifically protected under the Constitution), the court has never found an unlawful incidence of partisan redistricting.

Overall, Roberts has continued to try to narrow the reach of the Voting Rights Act and has remained steadfast that claims of discrimination must be made by individuals in specific circumstances and not by groups of people based on skin color.

In cases of blatant individual bias, Roberts has taken a conspicuous stand. For example, the 2016 case of Foster v. Chatman involved prosecutors in Georgia who had deliberately kept blacks off a jury, putting “B” next to the name of each potential juror to be struck. The Supreme Court ruled 7-1 for the defendant who had challenged the bias, and Roberts wrote the majority opinion.

A similar case of juror discrimination, arising from a Mississippi prosecutor’s elimination of African-Americans from a murder defendant’s juries, was heard recently, Flowers v. Mississippi.

New test of affirmative action, at Harvard

No ambiguity has surrounded Roberts’ rejection of the affirmative action programs that a narrow majority has upheld since the 1978 case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke. A major test of that landmark, involving Harvard, is now in a lower federal court and likely destined for the high court.

A US district judge in Boston is resolving the case brought by conservative advocates, who argued that Harvard unlawfully stereotypes Asian-American applicants and holds them to higher admissions standards as it favors blacks and Latinos under affirmative action practices.

Once the judge decides the case, which was subject to a three-week trial last year and a final hearing in February, any appeal would go first to the 1st US Circuit Court of Appeals, then to the Supreme Court.

Roberts’ past opinions suggest he would be sympathetic to the challengers’ case. It was controversy over affirmative action that led to one of the most public recent collisions on race at the court, between Roberts and Sotomayor, the first Hispanic justice.

In the 2014 controversy, the majority, including Roberts, voted to uphold an amendment to the Michigan state constitution that forbade using race as a factor in higher education admissions. Sotomayor dissented, using much of her opinion to declare racial discrimination still evident in public policy as well as daily life.

“Race matters to a young man’s view of society when he spends his teenage years watching others tense up as he passes, no matter the neighborhood where he grew up,” she wrote. “Race matters to a young woman’s sense of self when she states her hometown, and then is pressed, ‘No, where are you really from?’, regardless of how many generations her family has been in the country.”

Sotomayor, who early in her tenure spoke publicly about how she sometimes felt she did not fit in at the court, then declared, “Race matters because of the slights, the snickers, the silent judgments that reinforce that most crippling of thoughts: ‘I do not belong here.’”

She turned Roberts’ adage about the best way to stop discrimination on the basis of race (“stop discriminating on the basis of race”) against him by declaring that the best way “is to speak openly and candidly on the subject of race and to apply the Constitution with eyes open to the unfortunate effects of centuries of racial discrimination.”

Roberts took the unusual step of writing a statement, with no other justices joining, to respond to Sotomayor. “People can disagree in good faith on this issue,” he said, asserting that it “does more harm than good to question the openness and candor of those on either side of the debate.”

And as he has since he first began working as a lawyer in Washington, Roberts asserted that racial remedies, too, could “do more harm than good.”

That reinforced the line that can be drawn from Roberts’ position as a young lawyer in the Reagan administration to his views in the court’s center chair.