Indonesian President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo is on course for a second term in office, early results show, with the incumbent moving comfortably ahead of his longtime rival, former military strongman Prabowo Subianto.

Early “quick counts” of Wednesday’s ballots put Jokowi on around 55% of the vote, with Prabowo winning around 44%. “Quick counts” are conducted by a variety of credible polling agencies and have proved reliable in the past. Final official results will be announced by May 22.

Most pre-election opinion polls had given Jokowi a double-digit lead, despite criticism from analysts and former supporters who claim he has failed to deliver on issues such as human rights – and compromised his values of pluralism to score political points.

In a statement, Wednesday, Jowoki acknowledged he had seen the initial results, but cautioned supporters to “be patient” and wait for the official count.

“Let us reunite as one as brother and sister in the same motherland after this presidency and parliamentary election is over, reuniting and tending to our brotherhood as members of the same nation,” added Jokowi.

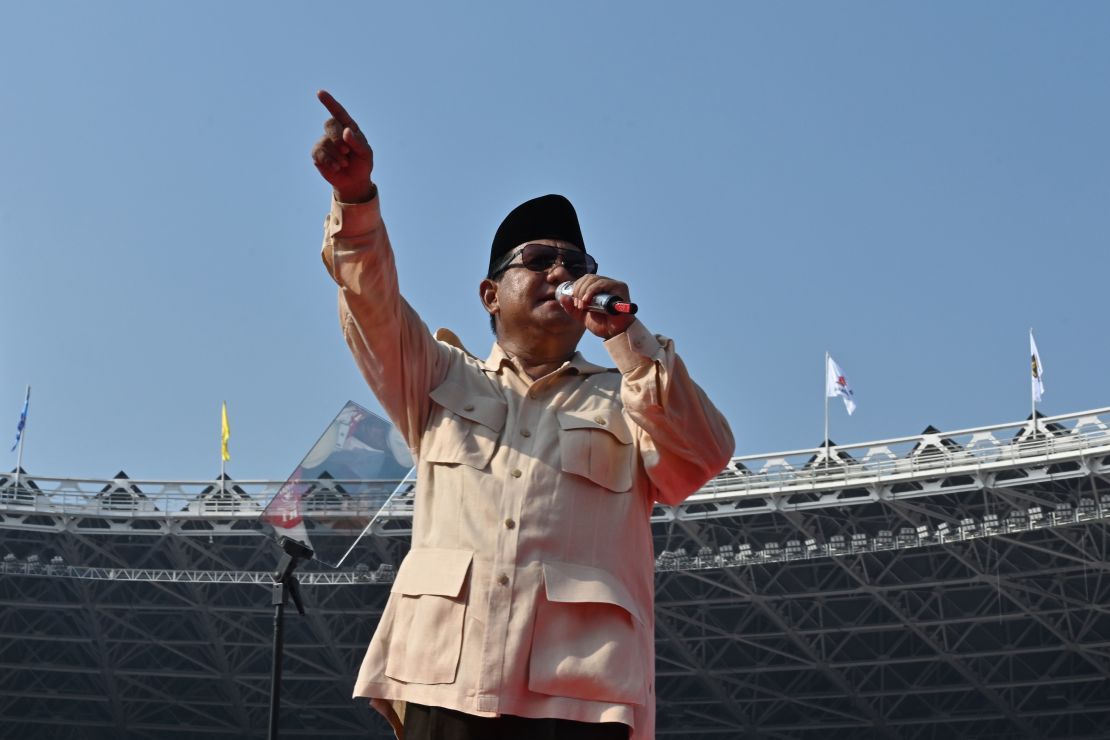

Opposition party leader Prabowo, meanwhile, appeared to dispute the early “quick counts,” arguing that alternative polls conducted by his own team had placed him in the lead.

Addressing supporters Wednesday, the former general asked supporters to “remain calm” and to continue to watch the results emerge.

Some 192.8 million people were eligible to vote across the archipelago’s 17,000 islands in what is the world’s biggest direct presidential election.

It was billed as one of the most complicated single-day ballots ever under taken. For the first time, Indonesia held its presidential and legislative elections on the same day, with more than 245,000 candidates running for over 20,000 seats. More than 800,000 polling stations and six million election workers helped to pull it off.

A logistical feat spanning mountains and jungles

Indonesians were actually asked to cast five ballots – for the president and vice-president, for members of the 575-seat House of Representatives, for the Regional Representative Council (or Senate), provincial legislators, and district and city councils.

Polling began at 7 a.m. local time and voters had until 1 p.m. to cast their ballots before polls closed and the counting started.

Ensuring this mega-poll in the world’s third largest democracy would go off without a hitch was a logistical feat, with election workers traveling by boat to remote islands, scaling mountains to reach hill-top villages and trekking through jungles – sometimes on horses – to bring ballot boxes within range of every voter.

“The logistics of this election are fiendishly complicated,” said Ben Bland, director of the Southeast Asia Project at the Lowy Institute.

“Indonesians are spread over hundreds if not thousands of islands, many of these places are very remote and mountain villages, you have to access some places by small boats, on foot in some cases. And remember that many different areas have different ballots because they’re voting for different local candidates,” said Bland.

“So for the election commission to get all these thousands of different kinds of ballot paper to 800,000 polling stations across Indonesia is a real geographical and logistical feat.”

But there has also been reported allegations of voting irregularities, with Prabowo and his team claiming there were voter lists that included names of the dead and those not eligible to vote and vowing to take action if their concerns were ignored. The Election Commission is investigating the claims.

Indonesia’s election watchdog has called for a revote for more than 300,000 Indonesians living in neighboring Malaysia because officials discovered invalid ballots, which were punched by non-voters, and other uncast ballots.

“There is convincing proof that the Overseas Election Committee in Kuala Lumpur did not carry out its task of conducting the 2019 election objectively, transparently and professionally,” the election committee said in a statement.

It comes after video purportedly showed pre-marked ballot papers for Jokowi in Malaysia.

While Indonesia is a relatively new democracy following the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998, Bland said the nation has a “pretty good track record” of keeping the election free and fair.

“Its important to understand just how hard it is for countries transitioning from authoritarianism to democracy to do so successfully, and how hard it is in a big developing country to hold successful elections,” he said, citing Nigeria and Afghanistan which have delayed their elections because of logistical problems.

“Meanwhile in Thailand there’s an impasse at the moment because of uncertainties of the counting process and the role of the military government in that so I think Indonesia deserves credit for the way its built up a pretty resilient election system,” he said.

The challengers

A former furniture salesman, Jokowi became mayor of Surakarta in 2005 and then Jakarta governor in 2012.

In 2014, he campaigned on a promise of creating jobs, bolstering human rights and cracking down on corruption. The public was sold and swept in the self-styled man-of-the-people over his military strongman opponent, Prabowo, now 67.

Once again, Jokowi was competing against Prabowo, a retired army general and son-in-law of former president and authoritarian dictator Suharto. His running mate is Sandiaga Uno, a businessman and vice governor of Jakarta who was named by Forbes in 2013 as Indonesia’s 47th richest man, with an estimated net worth of $460 million.

During campaigning, Prabowo seized on his rival’s economic failings, slamming Jokowi for allowing food prices to rise and calling for better quality jobs.

Jokowi’s choice of Ma’ruf Amin, a hardline Muslim cleric for his running mate, may have bolstered his religious credentials by appealing to Islamic hardliners that have traditionally supported Prabowo. But it could have also turn off some those who voted for him in 2014 for his commitment to religious freedom.

Youth vote

Some 80 million 18-35 year-olds – about 40% of the electorate – were eligible to cast a ballot this year and both candidates have made efforts to appeal to them.

Jokowi beamed a hologram of himself around the nation, featured his pet goat on social media, and made references to the television show “Game of Thrones.”

Prabowo, meanwhile, focused on issues such as unemployment which are likely to appeal to younger voters who are struggling with an unemployment rate of about 15.8%, according to World Bank figures.

“Millennials are very important to the two candidates,” said Hasanuddin Ali, chief executive of research company Alvara Research Center. “Millennial voters are also a key success factor in the Indonesian election.”

But analysts say there is widespread disengagement from young people towards politics and they are put off by high levels of corruption and distrust in the system.

“Some don’t feel like they’re being equally represented,” said Ella Prihatini, an academic with the Center for Muslim States and Societies at the University of Western Australia.

Others are concerned that minority rights continue to be eroded – over the past few years police raids and vigilante attacks on members of the LGBT community have increased and last year the country made moves to criminalize homosexual sex.

“I think it’s unfair to expect LGBT Indonesians to vote when we’re not even considered a part of this nation,” said Amahl Sharif Azwar, a 32-year-old gay Indonesian freelance writer who lives in Thailand.