“Father, I wanted to look you in the eye … I wanted to ask you why?” demands Anna Misiewicz as she confronts the parish priest she says abused her when she was just 7 and 8 years old.

“You touched me where you were not supposed to, my private parts,” Misiewicz says, matter-of-factly, telling him that his actions “really scarred my adult life deeply.”

“I still have nightmares … I am unable to sleep at night,” she tells her alleged abuser. “I still carry it inside me.”

The elderly man she is addressing exhales and shifts in his orange-and-brown-striped chair, as a religious service plays out on a TV nearby, in a home for retired priests in Kielce, central Poland.

The priest, identified only as Father Jan A., has never been charged with abuse. He pauses briefly, before saying: “I should never have done it, I should not have touched or kissed you … I know I shouldn’t have.”

“I regret it profoundly,” he says, insisting that he has reformed in the three decades since the alleged episode detailed by Misiewicz. “It was the devil who took his toll.”

The pair’s troubling meeting was captured on secretly filmed footage that is at the heart of “Tell No One,” a new documentary that has sent shockwaves through the Polish Catholic Church and wider society in the deeply religious nation.

Since its release on YouTube on May 11 the film, which details decades of sexual abuse by Catholic priests in Poland and shows victims confronting their alleged abusers, has been viewed more than 20 million times.

‘Erosion’ of Catholic Church

The Catholic Church – and its priests – enjoys a revered status and wields serious influence in Poland, where more than 90% of the country’s population is registered as Catholic.

The Church has long held powerful ties to politics; together with the late Polish Pope John Paul II, it is widely hailed for its opposition to the Communist regime that collapsed in 1989.

Marcin Zaborowski, political analyst at Visegrad Insight, told CNN the Catholic Church has been “fundamental” to Polish society. “The Church is part and parcel of Polish politics,” he said.

“The current government will find it difficult to distance itself from the Catholic Church,” Zaborowski added. Only a week before the film was released, Jaroslaw Kaczynski, leader of the conservative ruling Law and Justice Party, said: “Anyone who raises his hand against the church, wants to destroy it, raises his hand against Poland.” After seeing the documentary, he clarified his remarks at a rally, saying: “That does not mean that we support or tolerate pathology in the Church.”

But Zaborowski said the film “could be a game changer,” adding that it had “started the erosion of the position of the Catholic Church in Poland.”

The case that’s created the biggest outcry since the film’s publication is that of Father Franciszek Cybula, the priest of Lech Walesa, leader of anti-Communist movement Solidarity in the 1980s.

Confronted on the doorstep of a small, white house in Gowidlino, a village in northern Poland, Cybula is accused of abusing a 12-year-old boy, decades earlier. Cybula, who is unaware he is being filmed, admits he touched the boy in a sexual manner but tries to downplay his actions.

“There was a moment of caressing and then we went back to our daily business,” he says, arguing that “it never exceeded any inappropriateness,” and suggesting that the pair had “fondled” each other mutually. Cybula died before the documentary finished production.

Poland’s prosecutor general has issued an investigation into the alleged crimes detailed in the film.

“Tell No One” director Tomasz Sekielski told CNN he felt compelled to bring the sexual abuse to public attention after meeting several victims during his career as a journalist.

“The horror of their stories stayed with me, and I knew that I wanted to do something more on the subject; that’s why my brother and I decided to make the film.”

Taboo subject in Poland

It was difficult to find traditional investors willing to back the film because of its polarizing subject, Sekielski said.

Ultimately, he and his brother raised more than $100,000 to shoot the documentary via crowdfunding websites.

Sekielski says the response to it has far exceeded their expectations: “This film has been like a shock to Polish society and has managed to create real social awareness of a subject that has been very taboo in Poland.”

Sekielski says he does not know if Pope Francis has seen the film, which is available online with Spanish and English subtitles.

When CNN asked the Vatican if they had a comment on the film, they said they “would look into it.”

In response to the film, the Vatican’s ambassador to Poland, Archbishop Salvatore Pennacchio, told CNN: “The Pope is very concerned, and we express sympathy and solidarity.”

The Vatican has announced plans to send Malta’s Archbishop Charles Scicluna, the Vatican’s top sex crimes investigator, to Poland on June 13 to host a “study day” on abuse for Polish bishops on how to protect minors from abuse within the Church.

Archbishop Stanis?aw G?decki, president of the Polish Bishops’ Conference, said he had been “deeply moved and saddened” by the film.

“On behalf of the entire Bishops’ Conference, I would like all the victims to accept my sincere apologies; I realize that nothing can compensate them for the harm they have suffered,” he said in a statement, adding that the film would “definitely contribute to an even more severe condemnation of pedophilia, for which there can be no place in the Church.”

Following the film’s release, the Polish government proposed raising the maximum prison sentence for convicted pedophiles to 30 years.

But that’s insufficient, says Polish foundation Have No Fear, which helps victims of child abuse committed by the Catholic Church. The organization worked with the Sekielski brothers, helping to find victims who were willing to participate in the film.

Anna Frankowska, a board member of the organization, told CNN it had been “completely overwhelmed” by the reaction to the film: “It has generated a tsunami of calls from new victims to our charity.”

Since the film’s release more than 100 new cases have come to light, according to the charity. “On one hand it is wonderful, but on the other it is overwhelming as we do not have the resources to process all the cases,” said Frankowska.

“The government increase in jail time is not an effective tool,” she said, arguing that “it is more symbolic than anything, the courts need to actually start implementing these harsh sentences.”

‘Gesture gave me huge hope’

In February, representatives from Have No Fear delivered a report to Pope Francis in Rome, accusing 26 bishops in the Polish Catholic Church of concealing the perpetrators of sexual abuse of minors.

Marek Lisinski, a co-founder of Have No Fear, was one of those who met the Pontiff.

“The Pope took my hand in his hands and looked at me and … grew sad. It had a huge impact on me. Then … he kissed my hand. That gesture gave me huge hope,” Lisinski said.

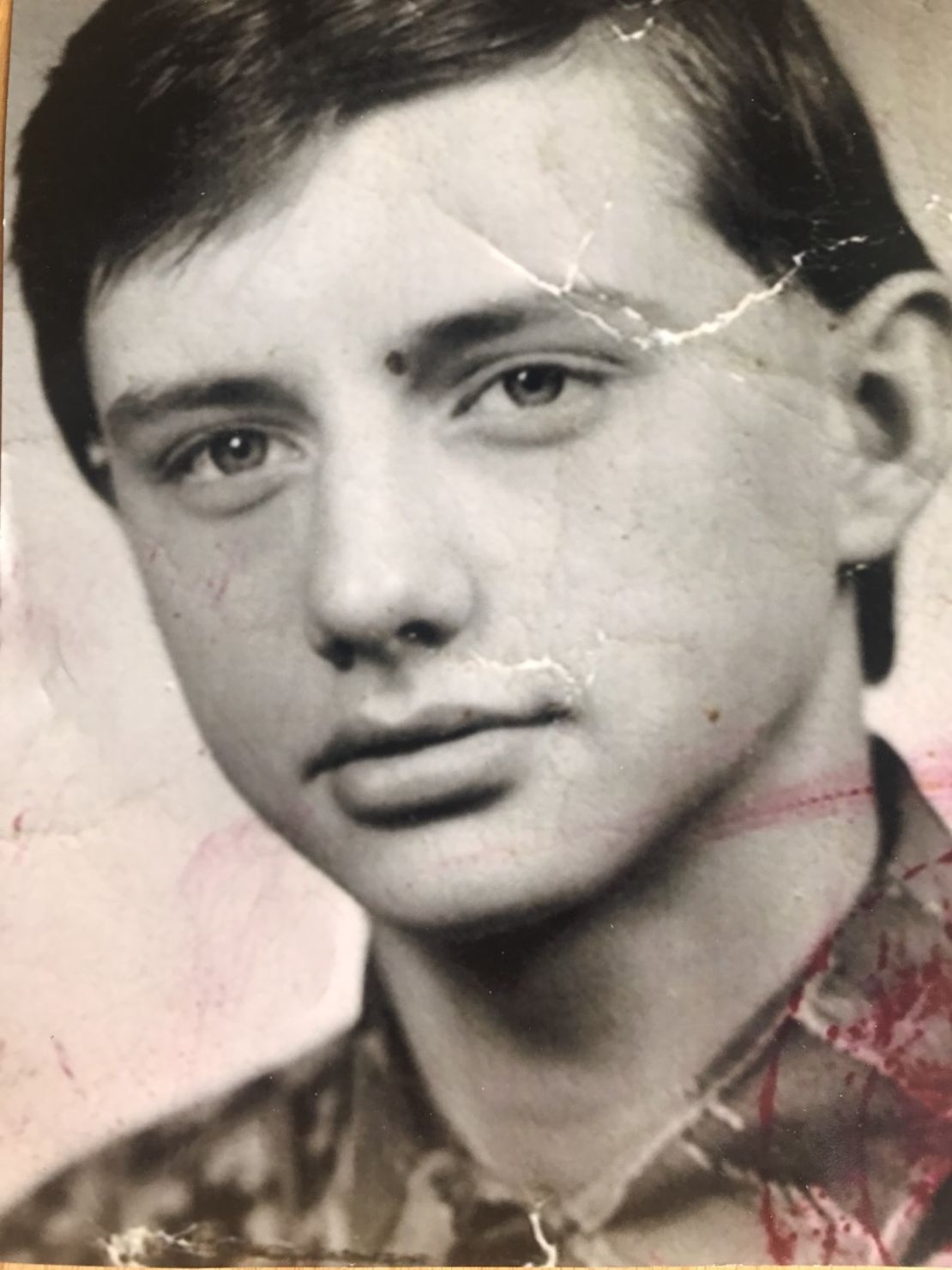

An abuse survivor himself, Lisinski told CNN how he had been groomed by a young vicar when he was a 13-year-old altar boy living in Poniatowo, in central Poland.

“It was in 1981 … You must remember these were totally different times in Poland, there was a shortage of almost everything. But he had everything, sweets, food. It’s important to understand what it meant in those days to get a sweet from someone,” he said, explaining that “times were tough.”

“He followed me into the toilet one day and started doing bad things to me,” Lisinski said.

When he tried to tell his mother about the abuse – on the same day that martial law was declared, in December 1981 – he said she was “more worried about the political situation in Poland rather than me.”

Lisinski said the sexual abuse “really hurt my life” and led him to become an alcoholic. Now sober, he now dedicates his time to helping other victims of abuse.

Have No Fear says it has yet to hear back from the Vatican about the report; its members are extremely frustrated at the way the Polish Catholic Church is dealing with what they see as a huge crisis in the country.

In March, Poland’s Catholic Church released a long-awaited report on the numbers of sexual abuse cases there in the past 28 years – the first time it has presented data on the scale of the problem.

According to data compiled by the church’s statistics institute and child protection center, 382 clergymen were reported for sexual abuse involving 625 minors between January 1990 and June 2018. Of these 58.4% were male, while 41.6% were female; more than half of the victims were under the age of 15, the report said.

Have No Fear says the numbers do not tell the whole story; they want access to church documents detailing the nature of the abuse, and to find out what – if any – punishments the alleged abusers faced.

In the absence of those records, the accounts of victims like Anna Misiewicz, who are willing to speak up about the abuse they say they faced as children, are all-important in helping to raise awareness of the issue.

Standing outside the pretty wooden church she attended as a child, Misiewicz tells the filmmakers about the day of her first communion, pointing out where she stood alongside her alleged abuser for a photograph to mark the occasion.

Dressed all in white, with a lace headdress in her hair and a half-smile on her face, there is little trace of the turmoil she was going through but, she says, “I was under great stress because … as a little girl I feared the photo would show that there was ‘something between us,’ as teenagers say now.”

“He destroyed my life,” Misiewicz says of her alleged abuser. “For me he does not even deserve to be called a priest.”