Russian President Vladimir Putin has been in power for nearly two decades, but he still has the capacity to surprise: This week, he unexpectedly showed that the Kremlin – on rare occasions – has a reverse gear.

To recap: On Tuesday, Russian authorities dropped a criminal case against a top investigative reporter known for exposing local corruption. The journalist, Ivan Golunov, had been arrested on an attempted drug-distribution charge that he and his colleagues insisted evidence had been planted by police.

As it turns out, the charges indeed had been fabricated. The police officers who arrested Golunov were suspended from active duty, and on Thursday Putin sacked two top interior ministry officials – the chief of internal affairs at the western district of Russia, Andrei Puchkov, and head of the Moscow directorate for drug control at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Yuri Devyatkin – in connection with the case.

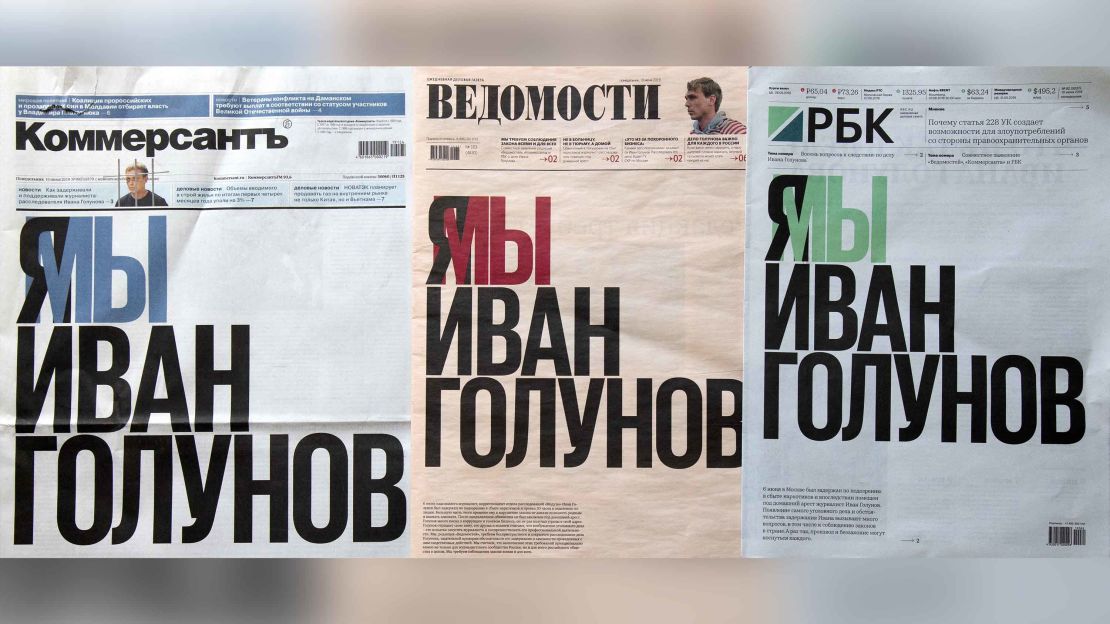

It was an unexpected reversal after an outpouring of solidarity from Russian civil society. Journalists rallied to Golunov’s side, staging rotating, one-person vigils outside of the main building of the Moscow branch of the Ministry of Internal Affairs at 38 Petrovka Street. Three leading newspapers on Monday published identical front pages with the slogan, “I/we are Ivan Golunov.” And campaigners organized a march in his support on Wednesday.

But Putin’s grip on power was never seriously in peril.

For starters, there was the response to Wednesday’s march. Organizers had hoped to build on the momentum of previous days, as thousands expressed interest in turning out for the demonstration. But the unexpected decision to release Golunov from house arrest clearly diminished interest. Golunov himself did not take part, and discussion about whether to proceed with protests sparked internal squabbling among Russia’s already fractured opposition.

And the authorities moved quickly and forcefully to shut down the unsanctioned demonstration that went ahead on Wednesday. When marchers turned out at the Chistye Prudy metro station in downtown Moscow, they were ordered to disperse by police. As they moved in the direction of 38 Petrovka Street, they were met by a cordon of police who effectively dispersed the march, with small squads of riot police collaring individual demonstrators and locking them inside police buses.

Demonstrators chanted, “Shame! Shame!” but it was all over within a few hours.

But while the protest in Moscow was far, far smaller than the wave of demonstrations seen in Hong Kong, the events of the week were still an unusual display of discontent with Putin. And the official climbdown in the face of street demonstrations was the most stunning: Russian authorities, for instance, have continued to hold US investor Michael Calvey, despite both domestic lobbying and diplomatic pressure from the US.

Voices from Moscow

What appeared to have mobilized some to take part in the protests was not necessarily Putin Fatigue, but resentment of local police, whom Russians distrust for corruption and arbitrary arrests.

“What is happening in this country is totally wrong, when drugs are being planted on a person who does not use them,” a young man from a city on the Volga River visiting Moscow told CNN. “The cops usually act like that.”

But his criticism did not extend to Putin.

“As for Putin, I can’t state that he is a bad ‘ruler’ or something like that. As far as we know, he is quite a good man. I think he should deal with this situation and find out why the law-enforcement bodies have got to the point of planting drugs on people who do not use them, while they fail to catch those who sell tons of them.”

Another woman, a Muscovite, said she didn’t watch the march in support of Golunov. But when told of the circumstances of his case, she said, “I stand for him.”

Asked if Putin’s reputation had taken a hit over the whole affair, she said, “I think yes, and we will do nothing about it.”

Such candor has its limits: Both individuals when approached by CNN asked that their names not be used.

Still, many outspoken Russians have taken to social media to opine on the meaning of the week’s events. And the Golunov case started a wider discussion about revising Article 228 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, the portion of the criminal code that covers drug crimes.

Writing on Twitter, Yevgeny Roizman, the opposition former mayor of the city of Yekaterinburg, took it further, saying “the entire Criminal Code of the Russian Federation must be revised, since it is an instrument for political persecution.”

That’s a larger discussion that the Kremlin, most likely, is not ready to entertain.

CNN’s Olga Pavlova in Moscow contributed to this report.