For the whale hunters, the inaugural expedition was a big success.

Hours after heading out to sea, their ships returned with the carcasses of two freshly harpooned minke whales, their huge, gaping maws draped off the sterns of the vessels.

“The catch was much bigger than expected,” said Yoshifumi Kai, chairman of the Japan Small-Type Whaling Association. “I’m very happy.”

At a ceremony before the fleet went out on July 1, Kai had given an emotional speech to an assembly of whalers, law-makers and the mayor of the northern Japanese port city of Kushiro.

“I’m so moved my heart is shaking,” he said.

This was an important day. Japan was lifting a 30-year ban on commercial whaling in its waters.

In 1986, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) announced a worldwide moratorium on commercial whaling. In late 2018, however, Japan decided to withdraw from the IWC – a move welcomed by its whale industry but condemned by environmental campaigners who believed it would threaten endangered species of whale.

But with Japan’s appetite for whale meat in decline, why is the country so committed to killing whales?

Whale experts

The septuagenarian Maeda brothers have decades of experience in pursuing whales.

These days, they run whale spotting trips on the frigid waters of the Sea of Okhotsk. But long ago, they used to hunt them.

Mitsuhiko Maeda, 73, and his younger brother Saburo, 71, worked in an eight-man team, harpooning and killing around 40 whales a year.

“Finding whales is a part of my life,” the elder Maeda said, as he steered his boat towards a minke whale to give the half a dozen Japanese tourists on board a closer look.

When asked about the resumption of commercial whaling, none of the tourists objected.

“Of course, it should restart,” the elder Maeda said. “Japan has a culinary culture of whales.”

Maeda has no plans to revive his former career, however. He enjoys showing tourists fin whales, the second largest of the world’s whale species.

“I will continue to lead cruises, and the whale hunters can catch the whales,” he said. “I want both to co-exist.”

While the 1986 moratorium brought the Maeda brothers’ whaling careers to a sudden halt, other Japanese hunters continued killing hundreds of whales every year for decades, using a special permit granted by the IWC for “scientific research.”

Japan killed 596 whales in the 2017 and 2018 hunting season, according to the IWC. Most of those were harpooned in the Antarctic, although Japan also hunted in the North Pacific.

Tokyo has defended its right to hunt whales, arguing it is a vital part of Japanese culture and maritime tradition.

“Japan is an island nation surrounded by the ocean and we have been using the whale as food since ancient times,” says Kiyoshi Ejima, a lawmaker from Japan’s ruling Liberal Democrat Party and a staunch supporter of the whaling industry.

Now that Japan has withdrawn from the IWC, whalers will no longer hunt in international waters but will pursue them in an economic exclusion zone, which extends 200 nautical miles from the Japanese coast.

A hunting quota has been set at 227 between now and the end of the year, according to Japan’s Fisheries Agency. That breaks down to 150 bryde’s whales, 52 common minke whales and 25 sei whales.

Of the three, only sei whales are listed as endangered.

But the plan to kill 227 whales in six months is just the beginning, according to whaling industry supporters.

“It’s the start-off,” said Ejima. “A kick-off point.”

That’s got some experts worried.

“There are fragile whale populations around Japan that cannot sustain commercial hunting,” said Patrick Ramage, director for marine conservation at the International Fund for Animal Welfare.

“These populations cannot feed a meaningful Japanese market – even if there were one for whale meat.”

Dying industry?

The Japanese whaling industry still faces one serious problem: appetite for whale meat is declining.

After the ravages of World War II, whale meat became a vital source of protein in Japan. In 1964, Japanese consumed 154,000 tons of whale meat, according to government statistics. And as recently as the 1970s and 1980s, fried whale was a common dish served for lunch to schoolchildren.

But by 2017, Japanese ate only 3,000 tons of whale meat. Per capita, that amounts to roughly two tablespoons of whale meat a year.

“Our immediate issue is how to make financial sense of it (whaling) going forward,” said Kai.

Critics argue that it’s a dying industry that is kept alive only by government subsidies. Japan’s Fisheries Agency has allocated the equivalent of about $463 million to supporting whaling for the 2019 fiscal year.

“If whaling is forced to sink or swim, this industry will drown very quickly,” said Ramage, from the International Fund for Animal Welfare.

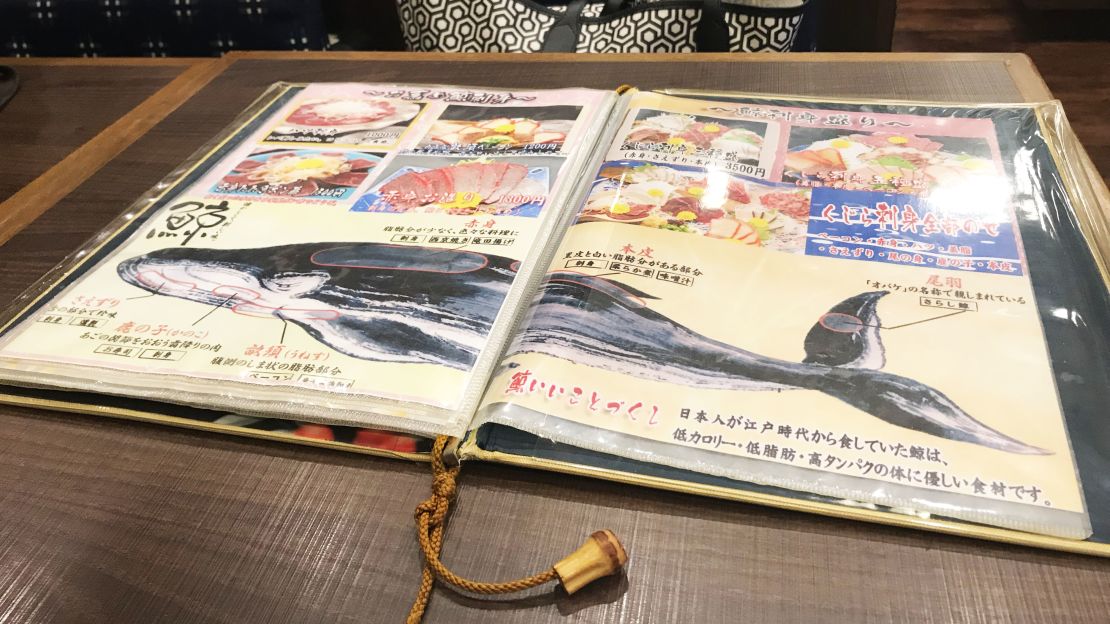

Still, restaurants including Taruichi, in Tokyo, decorate their entrances with paintings of whales at sea and proudly celebrate the culinary tradition of serving this niche meat.

Taruichi’s owner, Shintaro Sato, has printed leaflets celebrating the resumption of commercial whale hunting. “It was a dearest wish for us,” said Sato, who inherited the restaurant from his father. His family has been preparing whale meat for half a century.

In the kitchen, cooks carefully laid out garnished dishes of whale heart sashimi. The fryer bubbled with chunks of breaded whale meat. Waiters on the restaurant floor delivered platters of whale steak marinated in miso.

Sato said he hopes the relaunch of commercial whaling in Japan will help young Japanese rediscover whale meat.

To his critics, he said: “Let’s respect each other’s cultures and eat what each one eats.”