In January 2019, Nico Yennaris gave back his British passport, moved to Beijing and became a naturalized Chinese citizen. Aged 26, he adopted a new name.

From now on, he would be called Li Ke.

Growing up in east London, Yennaris had perhaps the most British of boyhood dreams: he wanted to become a famous soccer star. Born in David Beckham’s stomping ground of Leytonstone to a Cypriot father and a Chinese mother, Yennaris got off to a good start.

Aged 7, he joined the Arsenal FC Youth Academy, a production line for Premier League talent, and went on to play for the England national side at youth level. But after a series of injuries cost him a prestigious scholarship, relegating him to the lower league dressing rooms, Yennaris opted for another route to stardom.

He looked to China.

Earlier this year, Yennaris signed with Beijing Sinobo Guoan FC, a club that is now worth more than Italy’s AC Milan. Within months, he became the first naturalized player to score in the Chinese Super League (CSL) and to play for China’s national side, in a game against the Philippines.

Yennaris is not alone. In January, John Hou Saeter, who also has a Chinese mother, renounced his Norwegian passport to become Chinese and join Beijing Guoan. And they could soon be joined by other foreign-born players who can’t even claim partial Chinese ancestry. Two Brazilians and one Portuguese transfers are tipped to join the Chinese national squad in time for the Qatar 2022 World Cup. Players who are not ethnically Chinese can play for the Chinese side under FIFA eligibility rules after five years of residency in that country.

Their decision says as much about the rising power of a Chinese passport as it does about the nation’s monied sporting landscape. Perhaps more importantly, though, for a country in the grip of a Han nationalist movement, it also raises important questions around identity.

“China has such a black and white definition of what’s Chinese and what is not,” says Cameron Wilson, a Chinese football writer in Shanghai. “This actually challenges the notion of what being Chinese is in a very public way.”

The first Swedish footballer in China

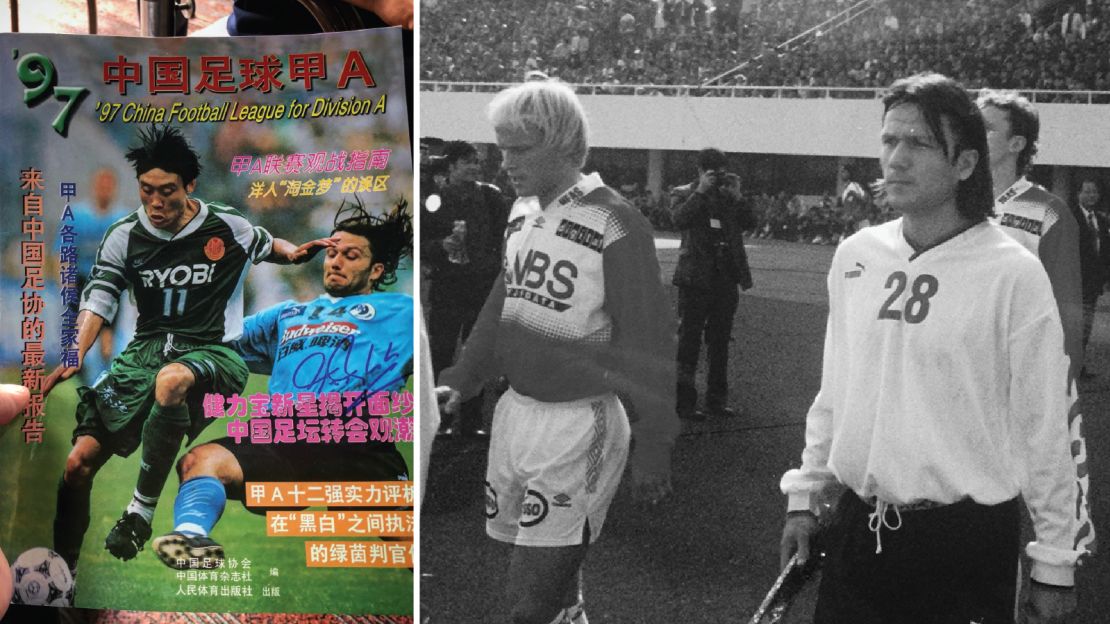

When Swedish midfielder Pelle Blohm arrived in northeast China to play for Dalian Wanda (now Shide) in 1995, the city was gripped by sub-freezing temperatures. “The Siberian wind was coming in from the bay. It was a winter but without snow,” remembers Blohm. “It was not pleasant.”

In the 1990s, the Swedish game was full of part-time professionals, the pay was bad and Blohm says he was yearning for adventure. Professional football was only in its third year in China when Blohm began playing in the Jia-A season – China’s equivalent of the Premier League, which became the CSL in 2004 – but Blohm says the stadiums often attracted 35,000 fans, although that was short of their 55,000 capacity.

The level of professionalism, however, was lacking.

“The players were smoking and drinking a lot … the football field was quite bad and there was never a dressing room. We had to get ready in the hotel,” says Blohm, who was immediately asked to cut his long hair short, to conform with the league’s strict appearance code. The Swede politely refused.

The club didn’t employ an interpreter for two months, and before then “nobody spoke in English or any other language except Chinese, as I can remember,” he adds. Blohm, who was the first Swedish professional soccer star to play in China, was paid in US dollar bills, but for months couldn’t find a bank account that would even take his foreign currency.

Dalian at the time was a city of 5 million people, with scant Western influence – no cafes, international brand-name shops or hamburgers, Blohm says. And few foreigners.

In the mid-1990s, most Chinese hadn’t been abroad. And those who did travel went on group tours run by government-approved operators. Often, travelers had to wait around six months for a passport, says Wolfgang Georg Arlt, who ran a Beijing-based company organizing Chinese tours to Germany throughout the 1990s.

“And at that time it was not really passport, it was a piece of cardboard called an exit visa,” he says. Couples were not often allowed to travel together – “it was either the husband or the wife who could travel. The other was staying behind as a hostage,” Arlt adds.

Rattled by the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union in 1991, China was worried that once holidaymakers saw what was beyond their border, they wouldn’t want to come home, he says.

“When I was in China, people were not even allowed to talk to a foreigner,” Arlt says. “If I asked someone, ‘Where is the railway station?’ he would have to go and report that.”

After one year – which Blohm nostalgically calls the “the most important year in my life” – the Swede left China. “Mentally, I was really tired,” he says.

Certainly, the idea that Blohm would trade his Swedish passport for a Chinese one was out of the question.

A point of national pride

By the summer of 2008, Beijing was dropping an astonishing $40 billion on the most expensive Olympic Games ever held. Its athletes won 51 gold medals at the Games, the most of any nation in the competition. And China was now the world’s third-largest economy, behind Japan and the United States.

The message being sent to the world was clear: with a soaring economy and growing political and cultural clout, China itself was now in the super league. But none of that changed the fact it still struggled at soccer.

China hasn’t been back to the World Cup since its 2002 tournament debut. And by July 2009 its team ranked 108th worldwide, according to FIFA. Furthermore, match-fixing and corruption were considered so rife that an ethics committee was founded to clean up the game.

As vice president in 2011, Chinese President Xi Jinping made getting better at the beautiful game a national goal. As a child, Xi had played football at school. Now he wanted the entire nation to fall in love with the sport.

Businessmen including Alibaba’s Jack Ma were encouraged to invest billions in the CSL, the all-male, 16-side championship. Wang Jianlin’s Dalian Wanda Group (DWG) has also poured hundreds of millions of dollars into the sport. Soccer academies and pitches were planned across the sprawling nation, and an ambitious scheme to hire thousands of foreign coaches offered everyone from professions to gap-year students financial incentives to teach young Chinese how to score.

As the cash came, so did the foreign talent – albeit, mostly fading stars or youngsters with no chance at the big time in their native leagues.

In 2012, former Chelsea striker Didier Drogba signed with Shanghai Shenhua – while this year, Manchester United midfielder Marouane Fellaini moved to Shandong Luneng. Transfer fees are never announced officially, but Fellaini is rumored to have been bought for about $13 million.

That number was eclipsed by reports this week that Welsh star Gareth Bale was leaving Real Madrid for a three-year deal with Chinese club Jiangsu Suning that would see him earn $1.2 million a week, before the Spanish side blocked the deal. Foreign players are not subject to the 10 million RMB ($1.45 million) salary cap that was recently imposed on domestic players, to prevent clubs from running up huge debts.

Homegrown talent

For Xi, however, the goal was not to attract foreign stars. It was to make Chinese ones.

As a result, CSL sides are only permitted to register four foreign players – and can only pay three at once – as well as one from a Chinese territory, such as Hong Kong, Taiwan or Macao. All CSL teams have maxed out that quota.

“That’s basically to ensure that Chinese players can get playing time,” said Wilson, the expert on Chinese football.

Some sides have used the Chinese territory rule to get more non-Chinese players on their books. Nigeria-born Alex Akande, for example, lived in Hong Kong long enough to naturalize there and now plays for Dalian as its one allotted player from the semi-autonomous Chinese city.

Foreign goalkeepers, however, have been outright banned from the league since 2001. And in 2017, clubs were hit with a 100% tax, also designed to stem capital flight, on players who cost more than 45 million RMB ($7 million), that levy going into a grassroots development fund for Chinese talent.

But Wilson says that the millions of dollars in investment hasn’t been able to make up for one crucial factor: China doesn’t have a football culture.

“I think they’re just not into football,” he says. “Nobody will tell you that. For a long time, even I was that person who was an advocate, saying: ‘Yeah there’s a lot of potential here, it’s a sleeping giant and it’s a massive goldmine waiting to be discovered.’”

Not a single Super League match sold out in this 2019 season, with stadium capacity averaging at 51% full. Most of the CSL teams make a loss. Manchester United, on the other hand, reported record revenues of £590 million ($730 million) for the year ending June 2018.

“The football culture we have in the UK is so profound and deep that it would take a long time for any country that doesn’t have that to generate it,” says Wilson, who is from Scotland.

Kids in China simply don’t grow up kicking balls around their block dreaming of bending it like Beckham.

Chinese for the long game?

If China lacks football culture, it’s been shooting to win in soft power and economic might.

In a promotional video posted by his club, Yennaris says he has “never questioned” his decision to leave British football, and – in sharp contrast to Blohm’s experience of Dalian in the 1990s – describes Beijing as being very “similar to big cities like London, Paris and New York.”

“Ten years ago, it was absolutely unthinkable that someone would choose a Chinese passport over a British passport,” says Philippe May, managing director of Arton Capital Singapore, which compiles the annual Passport Index.

Chinese nationality back then, May adds, would have severely limited a person’s freedom of movement, but the Chinese passport has gone from strength to strength over the past decade.

Arlt, the German tour operator, who is now a professor in sinology specializing in Chinese tourism, is skeptical. He believes that athletes becoming Chinese are banking on reversing that decision after having lucrative careers that were out of reach in their home nations, either because the market there was too competitive or simply not rich enough.

“I don’t think that these football players plan to spend the rest of their life in China,” he says. “If you earn $25 million playing football for three years in China, then maybe you’ll be happy to say goodbye to a million to get a Canadian or Portuguese passport,” he adds.

Colin Bloomfield, of Hong Kong-based immigration consultancy British Connections, says that reclaiming a British passport is possible, but applicants need to “provide a good reason why they wish to reapply” – and there is “no guarantee the UK will accept.”

On Weibo, the popular Chinese social media app, netizens have generally responded positively to the decision of Yennaris and Hou to naturalize, because of their Chinese roots. But the idea of Elkeson de Oliveira Cardoso, the Brazilian attacking midfielder simply known as Elkeson, becoming Chinese through residency, rather than having Chinese blood, is a more complicated issue.

In March, the Chinese Football Association decreed that all foreign players must be educated on Communist Party values, with clubs filing a written report on their performance each month.

CNN has reached out to China’s General Administration of Sport for comment, but had not heard back at the time of publishing.

For Yennaris, who is learning Mandarin and has memorized the national anthem, becoming Chinese has enabled him to realize that childhood dream of being a famous soccer star – just in a different country. The London-born midfielder looks set to make it onto China’s 2022 Qatar national squad, to be selected by the country’s Italian coach, Marcello Lippi, who won the World Cup for his home nation in 2006.

Yennaris says it’s his dream to help China get to the World Cup. But it’s a tall order – of the 32 teams in the competition, there are only four spots for sides from Asia.

But Yennaris says he has no regrets.

“In 20 years’ time, I’ll be able to tell my kids where I’ve come from and what I’ve done,” he says.

Whether he is Nico Yennaris or Li Ke when that conversation occurs remains to be seen.

Additional reporting by CNN’s Jordan Ashmore in Hong Kong and Serenitie Wang in Beijing.