In 2018, a severe drought brought Cape Town close to “Day Zero,” when it could have become the world’s first major city to run out of water.

Dam levels in South Africa’s Western Cape fell to below a fifth of capacity and the province suffered its worst water crisis in 100 years.

“Supplies were dwindling and it just wasn’t raining,” recalls Thinus Booysen, an associate professor at the University of Stellenbosch’s Faculty of Engineering, who had created a device in 2015 designed to help homeowners cut their power usage.

Seeking to reduce water waste, Booysen figured he could adapt the device to measure household water usage instead of electricity use.

When he found out that his daughter’s school faced a massive water bill each month, though, he realized he could have a much bigger impact by designing the device for schools and other institutions instead of targeting the homeowner market.

While households typically use a few kiloliters of water a month, Booysen says, many schools use 20 to 40 kiloliters in a single day.

“It was mind-blowing,” he says. “A lot of that was waste … [and] there was nobody taking ownership of it.”

How it works

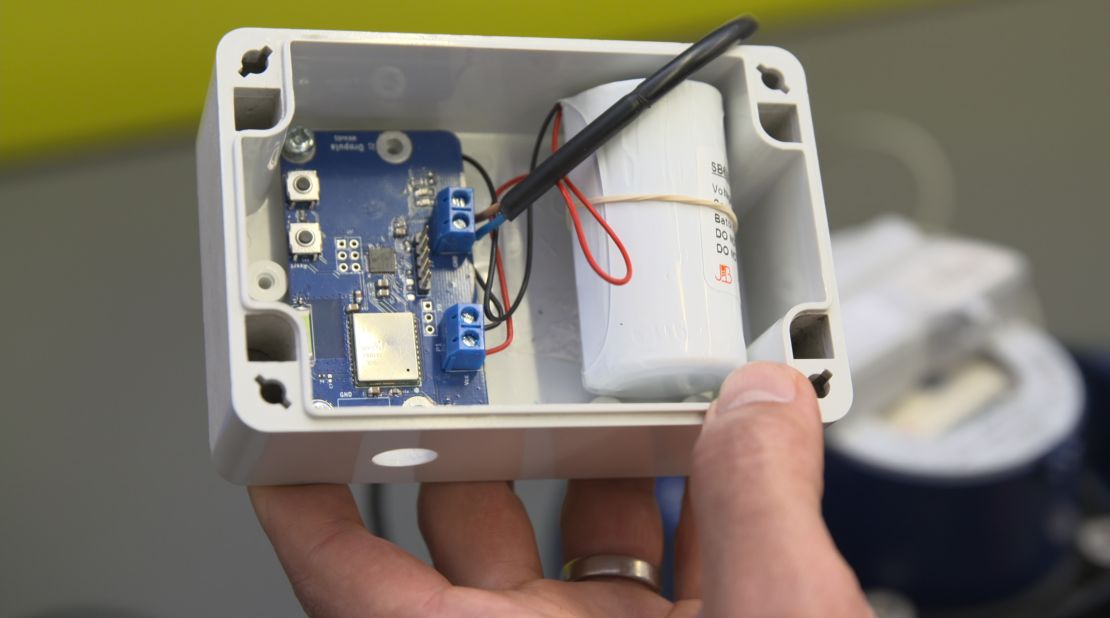

In 2015, Booysen launched a start-up, Bridging the Internet of Things (BridgIoT), to develop his smart water meter idea. Called Count Dropula, the meter reports water use once a minute in real time. Many conventional meters only record data once an hour.

The system uses an app to send the user SMS and email notifications, and can alert users to the exact time and place a spike in usage occurs.

“Within minutes, we would be able to notify the school to say, ‘Something has burst, something is leaking,’” says Booysen.

He soon discovered that a key issue was maintenance, with the poorest schools using by far the most water. Leaking toilets could waste 1,000 liters of water per day.

“We found that the biggest culprits are things like children not closing taps properly, but often that would be because the taps just don’t close,” Booysen explains.

Stopping the taps running dry

During the pilot, the invention saved one school more than three million liters of water in three months. Another reduced its water usage 55 percent in four months.

Businesses including Cape Talk radio station and Africa’s largest food retailer, Shoprite, became sponsors, partnering with the Western Cape Education Department to install the meters in 350 schools.

A Smart Water Challenge encouraged behavioral change among students, including bringing water to school and harvesting rainwater.

The schools saved more than $2.7 million and almost 550 million liters of water in 17 months.

Booysen has looked at expanding to government buildings, hospitals and hotels. There are plans to roll out the water meter across South Africa and Africa.

Getting bigger

Meantime, BridgIoT has branched out to sell a range of smart devices, including flooding sensors, animal trackers and electric water heater controllers designed to help users save money and resources.

The start-up, spun out of Stellenbosch University, is based at the school’s Launchlab incubator.

The incubator “gives us a very nice channel to take many of the ideas and intellectual property concepts that we generate in the university engineering department into the company – and then take them into the real world,” says Booysen.

The company isn’t profitable yet, but Booysen hopes it will be by early 2021.

Crisis averted - for now

At the height of the water crisis, Cape Town introduced restrictions limiting residents to 50 liters per person per day. A combination of interventions led to a citywide water usage reduction of close to 50 percent in less than three years, and Day Zero was avoided.

But water prices increased hugely between 2015 and 2018, and remain high today, with many fearing another crisis. The Western Cape government plans to install the meter in all 1,500 schools in the province, and estimates this could save more than 10 million liters of water, and $68,000, per day.

“The drought has come to an end, and rain has started to fall … we have enough water again to sustain ourselves,” says Booysen. “Now there is an awareness of how important, and how crucial water is in this region.”