Edward Latimer pauses mid-sentence to regain his composure. His black-tinted sunglasses, worn during a brief outbreak of autumnal sunshine in England’s capital, cannot hide his reddening eyes.

Two days into a hunger strike, the 31-year-old software engineer admits he is more emotional than usual. But though tired and hungry, it is the looming environmental catastrophe that’s really affecting his spirit.

One of thousands of Extinction Rebellion activists gathered in the heart of London for a planned two-week shutdown, Latimer has hope, but is also terrified of ecological breakdown and what has been described as the Sixth Great Extinction.

“I’m not here on a jolly,” he says, standing a few meters away from a tented kitchen feeding the cold, sleep-deprived protesters occupying London’s Trafalgar Square.

“Lots of police officers think we’re here to just have a laugh and a joke,” he continues. “When we’re doing things like dancing around, and when there’s lots of music playing, it can feel that way.

“It changes the conversation a lot when you’re saying to them: this is my time off work, this is a lot of my holiday, it costs a lot of money to be here. Being on hunger strike gives a better sense that this is a sacrifice for a cause.”

The environmental movement Extinction Rebellion recently kicked off a series of coordinated protests called International Rebellion, with demonstrations expected in 60 cities worldwide. In London, protesters have three goals: for the UK government to tell the truth about the climate emergency, for the UK to cut its greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2025, and for citizens’ assemblies to create policy to tackle the crisis.

This is Latimer’s first demonstration. The devout Christian says he grasped the severity of the crisis only recently, and realized that praying for humanity’s future was not enough. Though he loves steak, he became vegan. Though he wants to explore the world, he has vowed never to travel on an aircraft again.

In his collared shirt and sweater, Latimer bears little resemblance to “uncooperative crusties” – a ’90s stereotype of a vagrant youth subculture that UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson used last week to describe the environmental activists.

Johnson’s remarks can now be spotted around the city. ‘We are all Krusty,’ is painted below a drawing of Simpsons character Krusty the Clown, while a London mum pushes her one-year-old son in a pram decorated with a poster that reads: “I’m not Crusty. I just want a future.”

True, there are elements of the festival, of the bohemian, in protest sites dotted around the UK parliament. Flutes are played, drums are banged, some meditate, some perform modern dance on the roundabout – replacing the cars that would be there on any normal London day. When the heavens open, many happily sing and gambol in the rain.

But since first assembling on London’s Parliament Square last October, Extinction Rebellion, with its campaign of peaceful mass civil disobedience, has become one of the UK’s highest-profile environmental campaigns and attracts an assortment of British society to its ranks; from students to pensioners, doctors to farmers, seasoned activists to novices.

The activists have caused considerable disruption in London’s streets this week.

The Met Police has reportedly called on help from every force in England and Wales, arresting more than 1000 people in the past four days as activists pitch tents on the streets and glue themselves to buildings. On Thursday, activist began a planned three-day shutdown of London City airport. A senior officer said this week anyone protesting outside a designated area in Trafalgar Square was committing a criminal offense and liable to arrest.

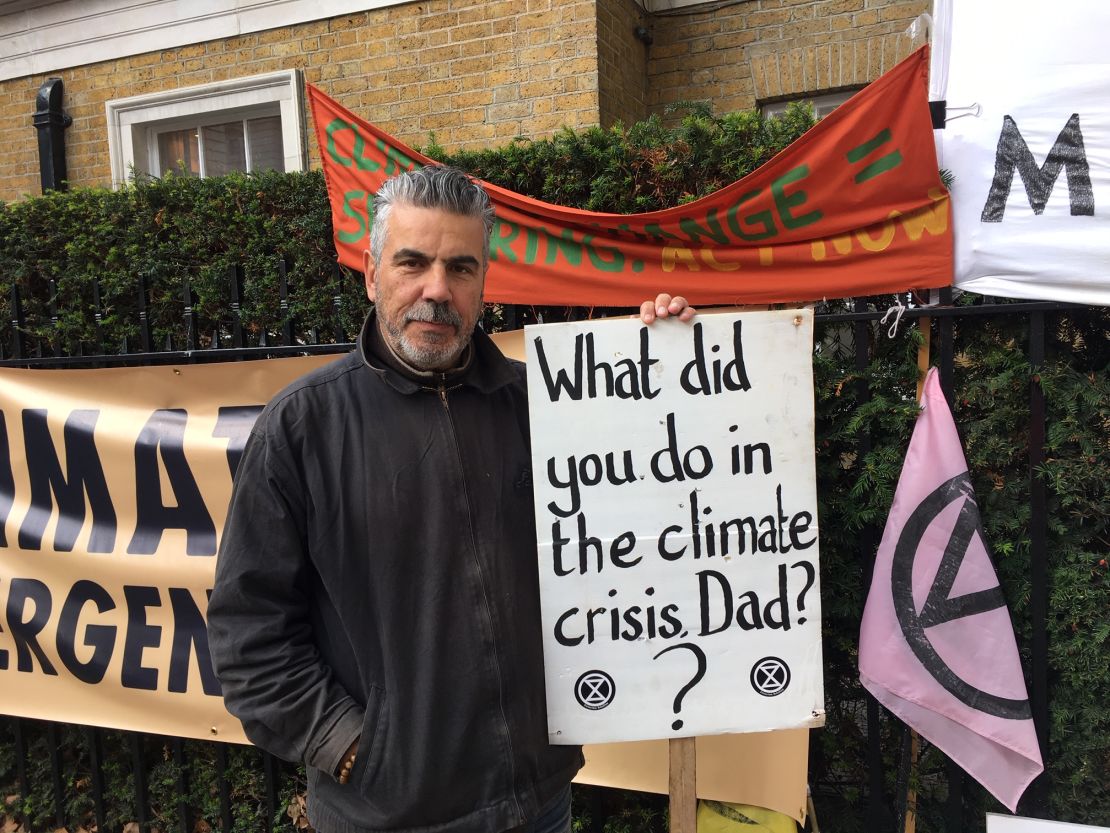

If the Queen were to crane her neck and peek through one of her Buckingham Palace windows, she might see a cluster of tents in St James’s Park. Camped on a nearby street, outside the government’s Treasury building, is 59-year-old Andrew David Peel, a delivery man using his vacation days to protest for the next two weeks.

“My daughter is 18 and she’s just gone to university, my son is 22 and has gone to China to teach English, how can I not tell them the truth? And, the sad truth is, they have no future unless they [governments] do something,” Peel explains.

“This is my duty and my responsibility to my children. The government is not listening, the environment movement has been trying to get them to listen for 30 years and they’ve failed and now it’s time to rebel.” Peel was one of more than 1,000 arrested during April’s climate protests in London.

“If that means breaking the law, then I’ll break the law and I’ll take the consequences, whatever that happens to be,” he says.

A few hundred meters away, in the shadow of Big Ben and Westminster Abbey, is an area occupied by the Scottish branch of the movement.

Edinburgh-based medical student Mikaela Loach has seen friends arrested over the last few days and is prepared to take part in a “lockdown,” attaching herself to something so that it’s harder for police to clear the streets.

“My family are supportive but they’re also quite scared, especially my mum, saying I’m a mixed-race woman on the streets of London interacting with the police force,” says the 21-year-old.

“I’m going to be a doctor one day and obviously I want my patients to trust me and to think I have their best wishes at heart, but this is one of the best things I could do to have that.”

According to Met officials, it takes a minimum of four officers to carry away any activist who refuses to stand when arrested. These last few days, those taken from road to sidewalk under arrest have usually been serenaded to cries of “we love you” by their fellow rebels.

At Whitehall, resting by the side of a government building, surrounded by officers and legal advisers, is a line of arrested activists. Their ages vary, but they are all white.

“It does have a race issue,” says art student Annabelle van Dort of the movement. “As a person of color, I cracked a joke before my first Extinction Rebellion meeting and said, ‘I’ll definitely be one of two’ and I was.”

“The way Extinction Rebellion works is that you rely on the police to treat you within the law and with respect,” she says, “and people of color, they can’t guarantee that so, maybe, they can’t sacrifice themselves for the cause the same way.”

Every activist mentions their privileged position in society, of the advantages bestowed of them by virtue of being well educated and living in a rich country.

On a street near Trafalgar Square, German-born university lecturer Petra Metzger is on lockdown, having attached herself to another protester. “I’m white, middle-class, educated. Who will make that change if not the privileged ones?” she asks, adding that arrest may jeopardise her chances of remaining in the UK after Brexit.

Just after midday on a sidewalk near parliament, half a dozen people had formed a semi-circle around a lady who, for the next 10 hours, would be one of many members of the group 1.5 Degrees reciting an abridged version of a report published last year by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). It said urgent changes were needed to reduce the risk of extreme heat, drought, floods and poverty.

“It’s a line in the sand,” said Debra Robert, co-chair of the working group, at the time. But from the IPCC’s bleak outlook arose a movement filled not only with urgency, but belief that ordinary people – with enough noise and personal sacrifice – can bring about global change.