A new study finds personalized lifestyle interventions not only stopped cognitive decline in people at risk for Alzheimer’s, but actually increased their memory and thinking skills within 18 months.

“Our data actually shows cognitive improvement,” said neurologist Dr. Richard Isaacson, founder of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic at NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Medical Center.

“This is the first study in a real-world clinic setting showing individualized clinical management may improve cognitive function and also reduce Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular risk,” Isaacson said.

The study was published Wednesday in the journal “Alzheimer’s and Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association.”

“We need more of exactly this type of clinical trial,” said Harvard professor of neurology Dr. Rudy Tanzi, who co-directs the Henry and Allison McCance Center for Brain Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“We spent so much time waiting for drug trials, but really there’s a lot we can do to maintain brain health with our lifestyle,” said Tanzi, who was not involved in the study.

“But it’s hard to convince the public to do that in the absence of clinical trials to tell us that sleep and diet and exercise and meditation matter,” he said. “The way this study was designed and carried out is a great guide for the future.”

Reducing risk is key

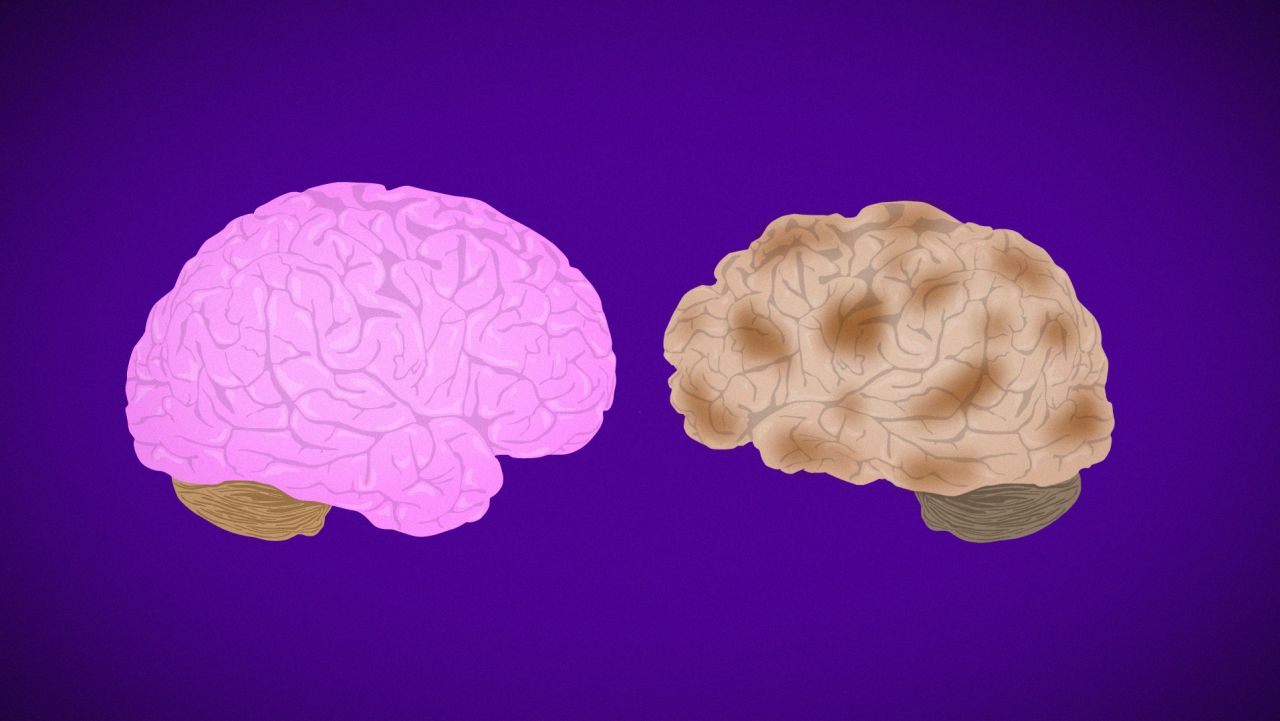

Alzheimer’s disease starts in the brain some 20 to 30 years before symptoms emerge. An estimated 47 million Americans are currently living with this type of preclinical Alzheimer’s. No drug exists to help them.

Some may be experiencing the subtle signs of cognitive loss; others are still blind to growth of the devastating plaques and tangles destined to steal their memories.

Evidence is growing that certain lifestyles changes such as diet, exercise and brain training might slow their mental decline, possibly even protect them from developing full-blown dementia.

But does one size fit all? Or do we each need a unique plan of action tailored to our specific risks factors?

Isaacson bet on the latter. Since 2013, clients at his Alzheimer’s Prevention Clinic undergo batteries of physical and mental tests. MRI scans are run to check for early signs of amyloid plaque buildup. Current and past medical problems, genetics, family history, nutritional patterns, exercise habits, levels of stress and sleep patterns are documented.

They are also asked if they want to participate in a study.

“Our study was designed to look at the effects of lifestyle intervention on cognitive function,” Isaacson said. “Does cognitive function go down? Does it stay the same or could it possibly improve?”

Isaacson and his team were able to enroll 154 patients between 25 and 86, all with a history of Alzheimer’s in their families. Most were not yet experiencing memory loss, but showed worrisome performance on cognitive tests.

A small group of 35 were diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The Alzheimer’s Association defines MCI as “cognitive changes that are serious enough to be noticed by the person affected and by family members and friends, but do not affect the individual’s ability to carry out everyday activities.”

Based on those results, each person was given a personalized prescription plan. Out of nearly 50 evidence-based interventions, on average each person was given 21 lifestyle behaviors to implement.

“Physical activity and nutrition were by far the two most important things on the list, but those were also personalized for each individual,” Isaacson said.

In physical activity, for example, the program might recommend aerobic interval training for one person, while using a balance ball or standing desk weight training might be recommended for another.

“Within dietary, we might say to consume caffeinated coffee only before 2 p.m. to protect sleep. No carbohydrates for 12 or more hours a day – that’s the intermittent fasting protocol,” Isaacson said.

The program looked at alcohol intake, dairy intake, minerals and vitamins, sleep hygiene tips, education to learn something new, listening to music, meditation, mindfulness, and more.

Results were hopeful

Isaacson found people with diagnosed mild cognitive impairment who followed 60%, or on average more than 12 out of 21 behavior changes, had better memory and thinking skills 18 months later.

Those with MCI who did less than 60% of the personalized behaviors showed no improvement. In fact, they continued to decline.

The second group of patients with genetic risk but no current clinical signs of dementia, called the prevention group, were able to get an equally impressive cognitive boost. It didn’t seem to matter if they followed less than 60% of the recommendations.

Isaacson is cautious about overstating the meaning of these results. The study was not designed to prevent Alzheimer’s, only to see if lifestyle changes affected cognitive function.

“We need more research, we need more clinics and more physicians to do it,” he said. “But I think this model is a roadmap for physicians and patients to work together to improve their brain health.

“We envision a day where people can go to their doctor and instead of hearing there’s nothing you can do, the doctor will say, ‘Well, we may not have the perfect answers, but here are 21 different things you can do based on your individual risk to protect your brain health.’”