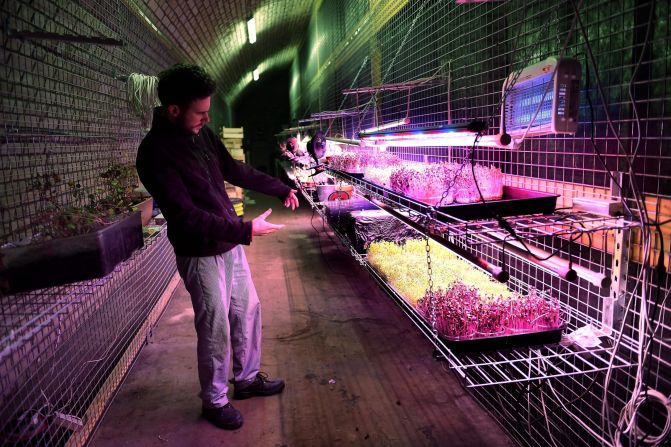

It might seem an unlikely place to be growing fruit, but deep beneath a South Korean mountain, a high-tech farm has been built inside an abandoned tunnel.

Once a functioning highway in the province of North Chungcheong, the tunnel’s sharp curve was deemed dangerous, so in 2002 it was closed and a more gently curved road was constructed nearby. Now this 2,000-feet-long (600 meter) tunnel is being used to grow salads, leafy greens, and strawberries.

It’s an example of “vertical farming” – a method of growing food without soil or natural light, in vertically stacked beds in a controlled environment. With no natural sunlight, here, LED lights are used to grow crops all year round.

They’re also what give the farm its pink glow – they emit only the spectrum of light that plants use to photosynthesize. More unusually, the music of Beethoven and Schubert is piped into the tunnel, because it encourages the produce to grow, according to Choi Jae-bin, CEO of NextOn, the company that created the farm.

Are vertical farms the future of food?

An appealing concept

With the world’s populations predicted to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, and cities predicted to become more crowded, hyperproductive indoor vertical farming built in unused spaces, or close to the consumer, has become an appealing concept.

Global warming, increasing soil erosion and water shortages are leading to declining yields in crops, but it’s hoped new methods of farming can help tackle the challenge of food production.

Traditional farms can take up a huge amount of space, often requiring forests to be cleared, and the vehicles that harvest crops burn even more fossil fuels. Traditional farms also use much more water than vertical farms.

“The world’s population is only going to grow but the environment is only getting worse to grow various vegetables, so I think it [vertical farms] will be the only alternative to provide healthy food to our table in the future,” said Choi.

Dickson Despommier – professor emeritus of public and environmental health at Columbia University, and a pioneer of vertical farming – agrees.

Find out more about Call to Earth and the extraordinary people working for a more sustainable future

Food derived from indoor farming is more nutritious and safer, he told CNN, as there isn’t the same risk of foodborne illnesses, pollution, allergens and pesticides. Plus, if a traditional farmer were to lose a crop they would often have to wait until the following year for a new harvest. With indoor farming, it’s the next week, he said. “The long-term loss is much less.”

Challenges for vertical farms

Critics say one of the biggest drawbacks of vertical farming is that maintaining a controlled environment and providing artificial light uses a lot of energy, which can mean a big carbon footprint. But that can be reduced by powering farms using renewable energy, and by increasing the efficiency of their LED lights.

Choi says his underground tunnel system has a naturally steady temperature, which means it needs less energy for cooling or heating.

Another criticism of vertical farming is that it’s mostly used to produce leafy greens, rather than higher calorie vegetables or crops. But Despommier says that will change, as more people acquire the expertise to grow different foods.

He says training and education is becoming available at institutions in Rotterdam, Shanghai, and in the US. “As soon as universities catch onto this (teaching indoor farming), they can fill it up with applicants faster than you can sit down to eat dinner,” said Despommier.

Read: How old smartphones are being used to find illegal loggers

Other high-profile vertical farms include Berlin-based InFarm, which builds hydroponic modular systems that can be used in supermarkets. California-based Plenty claims for certain crops, it can grow 350-times as much as a field of the same size, while in June, online grocer Ocado announced that it had invested £17 million ($21.5 million) in the nascent industry.

As for NextOn, Choi says his company has plans to build many more farms using the same technology, in urban locations – reducing the cost and carbon footprint of transporting food to shops.

“Plants easily grown at home, at nearby stores, at hamburger restaurants, or even at metro stations,” said Choi. “I think the system to grow crops far away from a city and transporting it will disappear.”