North Korean leader Kim Jong Un had nothing but praise for “the compatriots in the south” at the start of 2019, speaking of “the united strength of the fellow countrymen.”

Making predictions about a country as insular and cryptic asNorth Korea is often ill-advised, but it seems likely that such warmth towards South Korea will be absent in Kim’s upcoming New Year’s address.

It’s a dramatic about-face considering just last year, South Korean President Moon Jae-in was driving in an open top car with Kim Jong Un through the streets of Pyongyang, addressing thousands of cheering North Koreans and visiting the sacred Mount Paektu with Kim, realizing a “long unfulfilled dream,” as Moon put it.

But as talks between the North Korea and the United States have faltered, so have inter-Korean relations – a pattern seen repeatedly through the years.

North Korea has stopped talking or even listening to its southern neighbor in recent months. As things stand, the fledgling relationship between Moon and Kim is on ice. According to Cheong Seong-chang, an analyst at the Sejong Institute in Seoul, Moon is just not “pro-North” enough for Kim Jong Un.

A pro-engagement President

Since Moon took office, his administration has embraced a policy of engagement with North Korea, coaxing an initially reticent US President along with him.

Moon and Kim met four times over the past two years, signing agreements, pledging cooperation and demilitarizing parts of the heavily fortified border that divides the two countries.

However, it appears that was not enough for Pyongyang.

Cheong, the Sejong Institute analyst, said that North Korea believes if Moon’s administration was truly pro-North Korea, it “would have stopped the joint US-South Korean military exercises as asked and stopped the import of stealth fighters which can attack North Korea without being detected.”

“So in North Korea’s view, they are not pro-North at all,” he said.

North Korea continuously voiced stern opposition to joint US-South Korean military drills held this year – though some were scaled down and others were canceled – as well as Seoul’s decision to purchase F-35 stealth fighter jets from Washington. Pyongyang argues the moves are impediment to peace effort and responded by cutting off communication with the South and threatening to freeze Seoul out of nuclear talks with the US.

Officials from either side have never publicly confirmed whether a hotline set up between the two leaders has ever been used. The working assumption is, it has not.

Kim’s regime has also rejected offers of humanitarian assistance and refused meet the South Korean Red Cross this year.

“It is very difficult for North Korea to be seen to be cooperative to South Korea or conciliatory,” said a South Korean government official.

‘A door to North Korea’

South Korean Gov. Choi Moon-soon of Gangwon province told CNN that both sides need to buy time, and the key to doing so is simple: reopen Mount Kumgang, a serene tourist destination only a half hour drive from the demilitarized zone (DMZ).

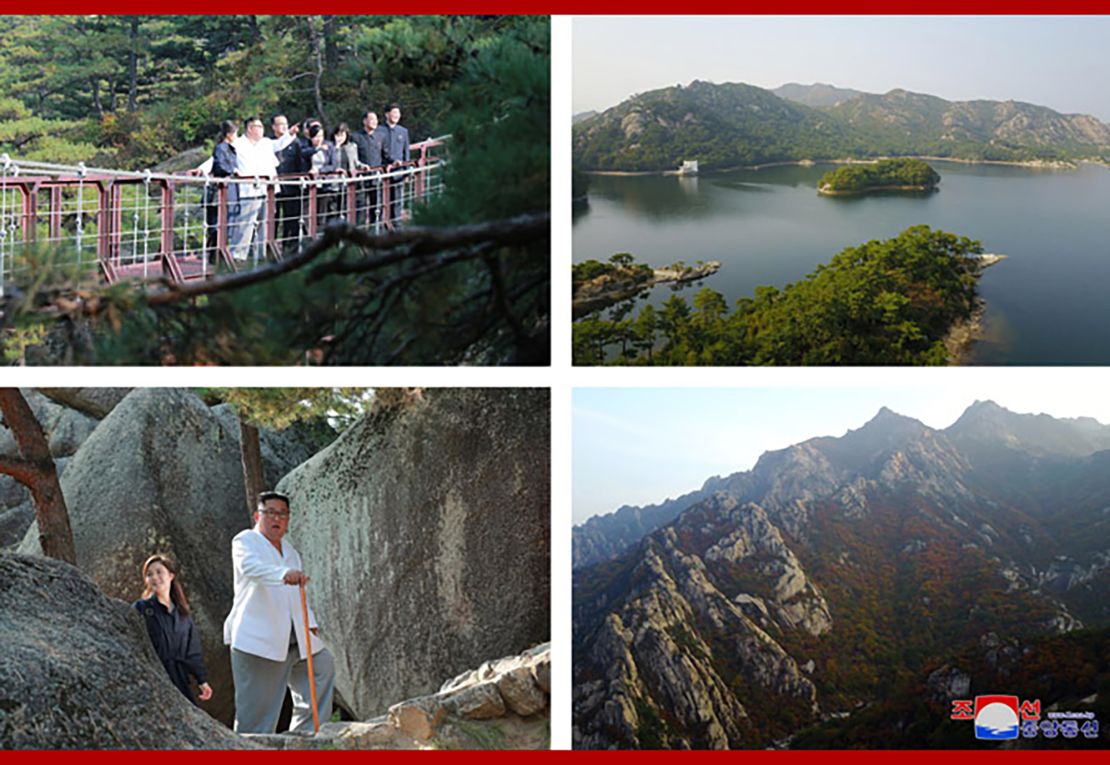

Kumgang was once a bustling joint tourist resort project between the two Koreas. But the dramatic beauty of the area belies the political turmoil that surrounds it.

Tours were suspended in 2008 after a South Korean tourist was shot dead by a North Korean soldier. Pyongyang claimed she had entered an off-limits military area.

Moon and Kim agreed to reopen Kumgang and a joint industrial park in the North’s Kaesong City when they met in Pyongyang in September 2018. Kim even announced it to his people, something he usually only does when confident something will happen.

Choi said the mountain is“a door to North Korea, a key to the solution.”

He and South Korean Minister of Unification Kim Yeon-chul are lobbying for the tours to resume. Both say tourism is exempt from the international sanctions levied against North Korea as punishment for its nuclear weapons and ballistic missile programs. But investing in joint entities that could allow Pyongyang to make foreign income is currently banned.

Choi said he believes Pyongyang is angry with Seoul and that it feels President Moon has not kept his side of the bargain.

“There were six times of summit after Pyeongchang Winter Olympic Games,” Choi said. “Each of them were gorgeous ones … big smiles, big hands, big hugs, and big promises and then nothing.”

“They’re angry about it,” he said.

Kim visited Kumgang in October, and slammed the resort as “shabby” and backward.” He said the South Korean-built buildings had to be torn down.

Seoul’s suggestion that the two sides meet and discuss matters further fell on deaf ears.

Kim’s visit was seen by experts as a way to put pressure on Moon to unilaterally break sanctions, something he has not been willing to do without permission from the US.

US President Donald Trump has not given Moon the green light to reopen Kumgang. In April, he said “this isn’t the right time” to grant North Korea economic concessions. Washington is concerned Pyongyang could use money from the resort to fund its nuclear and missile programs and has pushed for a deal that would see North Korea give up its nuclear weapons and missiles up front.

Choi has appealed to North Korea to allow him to take a delegation of hundreds of potential investors in Mount Kumgang across the border. He’s confident of approval, but not before the end of the year, the deadline North Korea gave the US to change its “current way of calculation” in nuclear negotiations.

Choi has met with Trump administration officials in Washington to make his case for reopening Kumgang. He said they listened, but at this point did not agree.

The clock is ticking

Choi and analysts who study North Korea worry the clock is ticking, whether or not the US believes Pyongyang is serious about its deadline.

The State Departments top official in charge of negotiations with North Korea, Stephen Biegun, has called the deadline “artificial.”

Biegun visited South Korea on Monday in an effort to get the stalled talks back on track as tensions between the two Koreas and the US continue to rise.

“It is time for us to do our jobs. Let’s get this done. We are here and you know how to reach us,” Biegun said at a news conference.

However, there is concern that North Korea has been able to drive a wedge between Moon and Trump’s administration, with Seoul more focused on reconciliation and Washington on nuclear negotiations.

“I think there’s been a missed opportunity here for the US, we never fully committed or backed the inter Korean peace process,” said Adam Mount, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Federation of American Scientists. “There would have been some real benefits for us if we did so but essentially what happened is the North Koreans split negotiations into two separate tracks and kind of played us off each other.”

Now, Choi worries there isn’t enough time for negotiations to succeed. As the head of MBC media in 2008, he helped negotiate the New York Philharmonic Orchestra’s groundbreaking visit to Pyongyang. That trip took two years to negotiate, he said.

“At this stage … the time is too short,” he said.