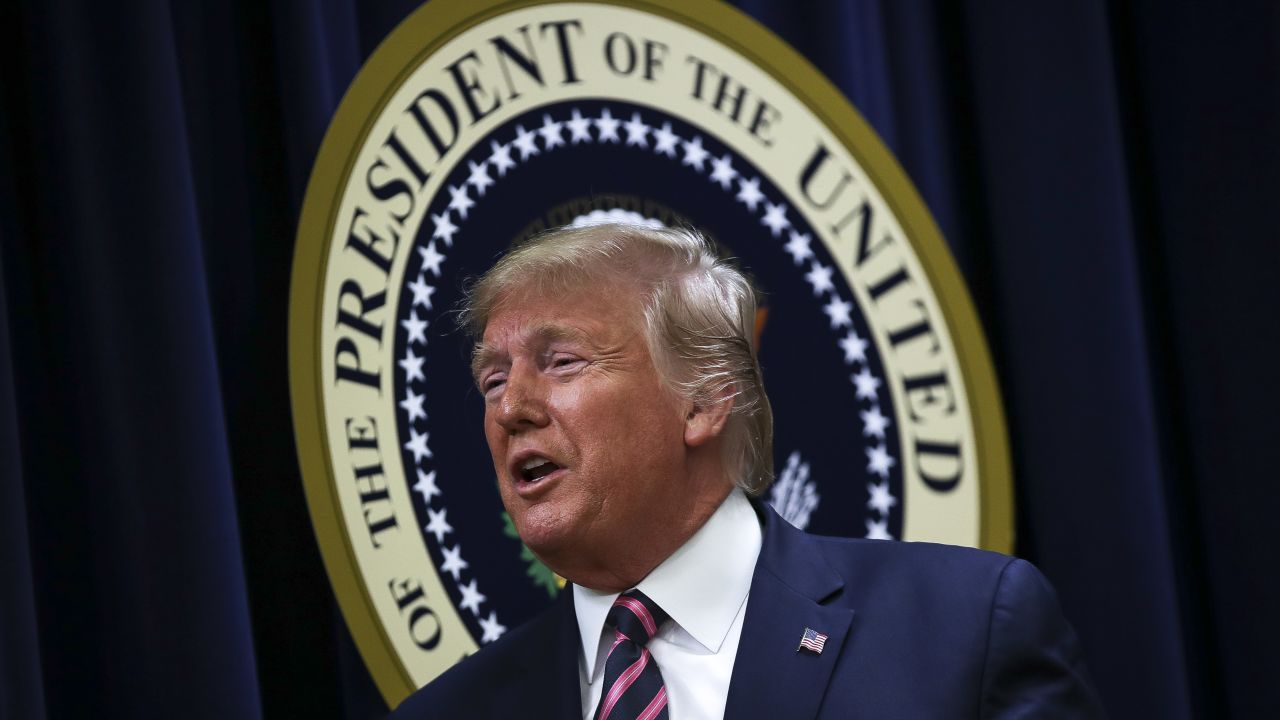

Impeachment proceedings against an American president should be a serious democratic exercise aimed at finding the truth. But remarks from both sides of the aisle suggest the process against Donald Trump will be a futile vote along party lines.

There’s something broken in the system, experts say, and Americans are losing faith in it. Americans’ public trust in governance is at near historic lows and while the public is split on impeachment, a Pew Research poll shows the majority of Americans don’t think either party will be fair or reasonable.

The US is but one on a long list of nations growing frustrated with their democracies. If last century was defined by liberal democracy’s rise, the 21st century is so far defined by its decay.

On paper, there are more democratic countries and elected leaders in the world than ever, yet several indexes show a clear downslide in the practice of democracy overall.

One index, by the Varieties of Democracies Institute (V-Dem), shows either no overall democratic improvement or a backslide in 158 of 179 countries studied between 2008 and 2018.

Twenty-four of those countries, including the US, have experienced such significant setbacks that they are actually “autocratizing,” according to V-Dem, which observes the world as undergoing its third wave of autocratization.

The numbers are more astounding when you take population into account – more than a third of the world is now living in a country undergoing autocratization. That surge has happened remarkably fast, from 415 million people in 2016 to 2.3 billion in 2018, according to V-Dem.

This erosion is happening around the world, and perversely, in many cases the leaders challenging democratic norms were themselves democratically elected. In Latin America, it’s in Brazil and Venezuela. In Europe, it’s Poland, Hungary and Turkey. It’s India and the Philippines in Asia, and Mali and Burundi in Africa, to name a few.

V-Dem also noted for the first time a rapid spread of toxic polarization and hate speech, with more countries regressing than advancing.

This polarization has fractured parliaments across Europe, creating political deadlock in countries like Italy and Spain. British voters were so frustrated that their splintered Parliament could not deliver Brexit that they just elected the biggest Conservative government since the country’s divisive years under Margaret Thatcher.

The Trump effect

The erosion of democracy in the US and across the world started well before Trump. Globalization, US wars in the Middle East and the rapid advancement of technology – automation and communications tools – have all contributed to this downslide, according to Larry Diamond, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

But this decay became “dramatically worse” when Trump became president, Diamond said.

Trump has loudly voiced his dislike for democratic norms and institutions, often through his Twitter account, where he has attacked the free media, the judiciary and the electoral process itself. These attacks have had a ripple effect around the world, inspiring “chauvinist politicians” to act more autocratically, Diamond told CNN.

“Democracy was expanding in the 1980s and the early 1990s, and particularly after the fall of Berlin Wall, and then the collapse of the Soviet Union, the US and Europe together were the dominant powers in the world, and democracy normatively and in terms of the global power and energy behind it, was the way the world was going. And there was a lot of money and diplomatic capital and global power and energy being invested in developing democracy – sanctioning, punishing, marginalizing, isolating diplomatically countries that were moving the wrong direction,” Diamond said.

That energy has waned. Diamond believes that the Iraq and Afghanistan wars played a significant part, negatively associating in people’s minds the promotion of democracy and the use of military force.

Then Trump ascended to the presidency, openly praising autocratic politicians, like Russian President Vladimir Putin and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, even meeting and shaking hands with North Korea’s Kim Jong Un.

“He has trashed our allies, and our western democracy alliances, and this happened at the very same time that China and Russia were surging in their global power ambitions, and developed new means, digital and otherwise, new instruments, and made plans to intervene, to roll back democratic gains, to scourge and pre-empt new democratic breakthroughs, because they don’t want any more examples of revolutions that could give their own people ideas,” Diamond said.

As a result, there is much more competition between democracy and authoritarianism than there was last century, according to Diamond, who said the rise of far-right populist parties in Europe were also giving democracy a bad name.

“So people are saying, well, if Europe and the United States don’t look like brilliant generous examples anymore, the illiberal, chauvinistic politicians in emerging or protested democracies like India, you know Modi looks around and sees Trump doing this, and sees Orban doing this, and sees Poland doing this, and he thinks, ‘What the hell, I can do it too,’” he said.

India’s 2019 vote was the world’s biggest exercise in democracy, yet it culminated with the re-election of an increasingly autocratic leader.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s nationalist BJP leads a government that openly favors the country’s upper caste Hindus and shuns India’s nearly 200 million Muslims, most recently through a new citizenship law that critics view as discriminatory towards Muslims. It clamped down on the independent media and dissenting voices ahead of an election this year, and accepts donations from big businesses it no longer has to disclose, thanks to a law it successfully changed.

It’s moving toward a model that V-Dem calls an “elected autocracy.” Instead of dictators, elected “strongmen” continue autocratic rule. They simply make their countries look more democratic than they are.

Russia is a longstanding example. Vladimir Putin has essentially led the nation for two decades by crushing the political opposition and free media, controlling information and manipulating the electoral process.

It’s the same story in Turkey, where President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has taken his leadership style straight from Putin’s playbook, ruling the nation now for more than 15 years. He was re-elected last year after transforming Turkey’s governing executive, granting himself extraordinary power in the process.

Hungary – with its crackdown on the media and civil society, and concentration of power at the top – is beginning to resemble Russia and Turkey under the leadership of Prime Minister Viktor Orban.

Even in bastions of democracy like Britain, people are showing an appetite for a little less voting and a little more action. Before the recent election, the Hansard Society found that 54% of people in the UK said the Britain needed a strong leader “wiling to break the rules,” while 42% thought the country’s problems could be dealt with more effectively “if the government didn’t have to worry so much about votes in parliament.” The number of people who “strongly disagree” that political involvement can change the way the UK is run is at a 15-year high, at 18%.

What’s next?

The future for democracy is not all doom and gloom. As longstanding democracies with large populations lose a little faith, smaller nations are rising. Twenty-one countries showed an improvement in democracy over the past decade, according to V-Dem. It also noted at least seven nations were transitioning to electoral democracies between 2008 and 2018, including Tunisia, the Gambia, Sri Lanka and Fiji.

And the protesters who have demonstrated in Hong Kong for six months against Beijing’s grip on their region show a real hunger for democracy where it’s absent.

In Iran, deadly protests against fuel price hikes expose a bitterness toward an oppressive regime, while protesters in Lebanon and Iraq are demanding cleaner governments that better serve the masses.

Paul Cartledge, a Cambridge University historian and author of “Democracy: A Life,” says that democracy is clearly going through a “bad patch” and is under threat, but the world isn’t on the verge of a new wave of fascism.

“A lot of people have voted in certain ways because they feel that the gap between themselves and those in power is too big, and they want someone to come in from the outside and smash through. It’s just been disastrous,” he told CNN.

“But I think this period will wake people up,” he said. “In 10 years from now, I think we’ll see some change.”