Editor’s Note: Caroline Polisi is a federal and white collar criminal defense attorney at Pierce Bainbridge in New York City and an adjunct lecturer in law at Columbia Law School. She frequently appears on CNN as a legal analyst. Follow her on Twitter: @CarolinePolisi. The views expressed in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

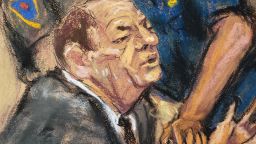

Harvey Weinstein’s conviction is a win for New York state prosecutors and a win for sexual assault survivors throughout the United States. That he was not convicted on two counts of predatory sexual assault does not deter from that reality. After being remanded, he is in custody and facing at least a five-year sentence.

As New York District Attorney Cy Vance noted in a post-verdict news conference, “Rape is rape, whether it is committed by a stranger in a dark alley or by an intimate acquaintance.” Until now, many prosecutors were still extremely reticent to bring charges in certain kinds of so-called “acquaintance rape” incidents, primarily because these cases are among the most difficult to prove.

For too long, prosecutors – and much of society – were influenced by flawed assumptions about the nature of consent, stemming from the very beginnings of our criminal justice system. For example, until quite recently, a husband could legally rape his wife with impunity under exemptions to the criminal code in most states. Shades of this outdated logic colored Weinstein’s defense: The alleged victim willingly went to Weinstein’s hotel room, or she maintained a cordial – and at sometimes intimate – relationship with the movie mogul after her assault. Donna Rotunno, Weinstein’s lead defense attorney, even reiterated these assumptions when she noted in an interview given during the trial that she herself had never been sexually assaulted because, as she put it, “I would never put myself in that position.”

But jurors just shattered a long-entrenched myth by proving that they can understand the nuances of complex relationships and appreciate that victims of sexual assault might behave differently than one might expect, nor is there a predictable pattern for how and when a victim may report abuse.

For example, jurors convicted Weinstein of criminal sexual assault in the first degree in connection with an assault against Mimi Haley, who testified that he raped her after she agreed to meet him at his SoHo apartment. Three weeks later, Haley went to Weinstein’s hotel in Tribeca, where she engaged in sexual contact again with him, which she said she did not consider to be rape at the time. Jurors also convicted Weinstein of rape in the third degree in connection with an assault against Jessica Mann, who described in court the consensual sexual encounters she had had with Weinstein before and after her assault in 2013. In other words, both victims had complicated relationships with Weinstein, thus neither were “ideal” witnesses.

Jurors did not find Weinstein guilty of two counts of predatory sexual assault: They would have had to have believed the testimony of actress Annabella Sciorra, who claimed Weinstein raped her over 30 years ago. That the jury did not convict on these two top charges (which could carry with them life in prison) shows that they considered all of the evidence individually and were not simply bent on finding him guilty because of preconceived prejudices that they had coming into the trial. It shows that the jury process maintained its integrity and that juries are capable of separating their own personal beliefs from the facts presented at trial.

I’ve asked in previous columns whether the #MeToo movement, catalyzed over two years ago by bombshell revelations about Weinstein’s alleged decadeslong sexual predation, would infiltrate our criminal justice system in meaningful ways. It has clearly shattered cultural norms and radically altered our collective understanding of acceptable behavior, but it was unclear early on whether any real change would happen in the criminal justice system. This verdict has solidified #MeToo not just as a social and political movement but as a legal movement too.

The landscape in which law enforcement and prosecutors can investigate and try sexually violent crimes has fundamentally changed, now that there is demonstrative proof that juries can convict even in cases with no physical evidence and even when the victims maintained contact with the accused after the assault.

Weinstein’s lawyers have already asserted their desire to appeal the jury’s decision, although it is unlikely they would win any such claim. Additionally, he’s been charged in Los Angeles with forcible rape and sexual battery, among other serious violent sex crimes, stemming from entirely different alleged incidents than those charged in New York. Weinstein has not yet pleaded in this case, but if convicted of the charges in LA, he faces up to 28 years in prison.

It truly is a “new day” for sexual assault prosecutions throughout the country. #MeToo has left an indelible mark on our criminal justice system and will result in more prosecutions and convictions for sexual violence. Additionally, today’s verdict will encourage more victims of sexual assault to come forward and report their abuse, with the knowledge that although the road to justice will not be easy, it will at least be a possibility. And that is so much more than they ever had before.