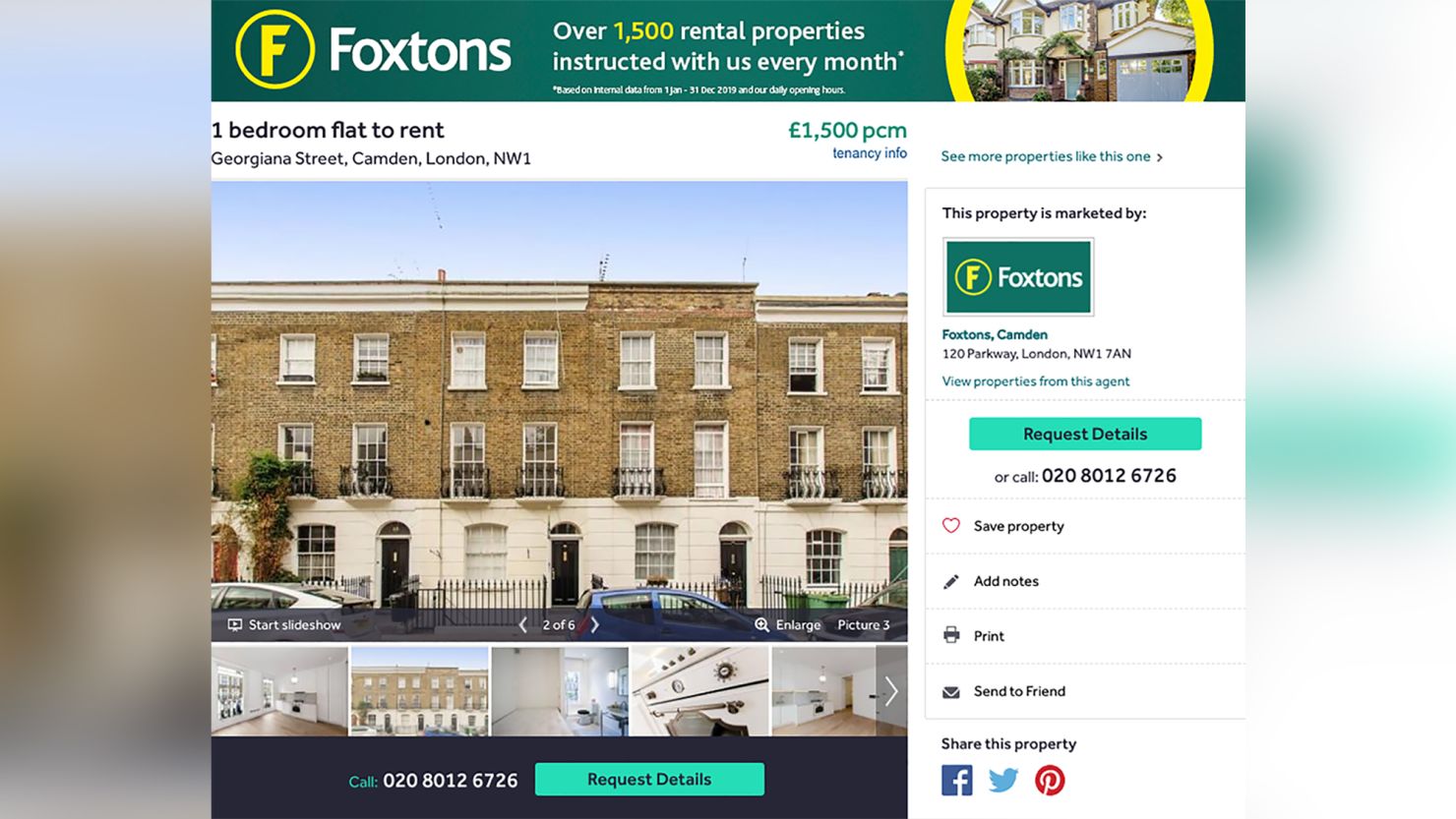

At first glance, the advertisement looks impressive: A one-bedroom flat in London’s trendy Camden Town, situated in a pretty townhouse and boasting “high ceilings” and “designer marble worktops.”

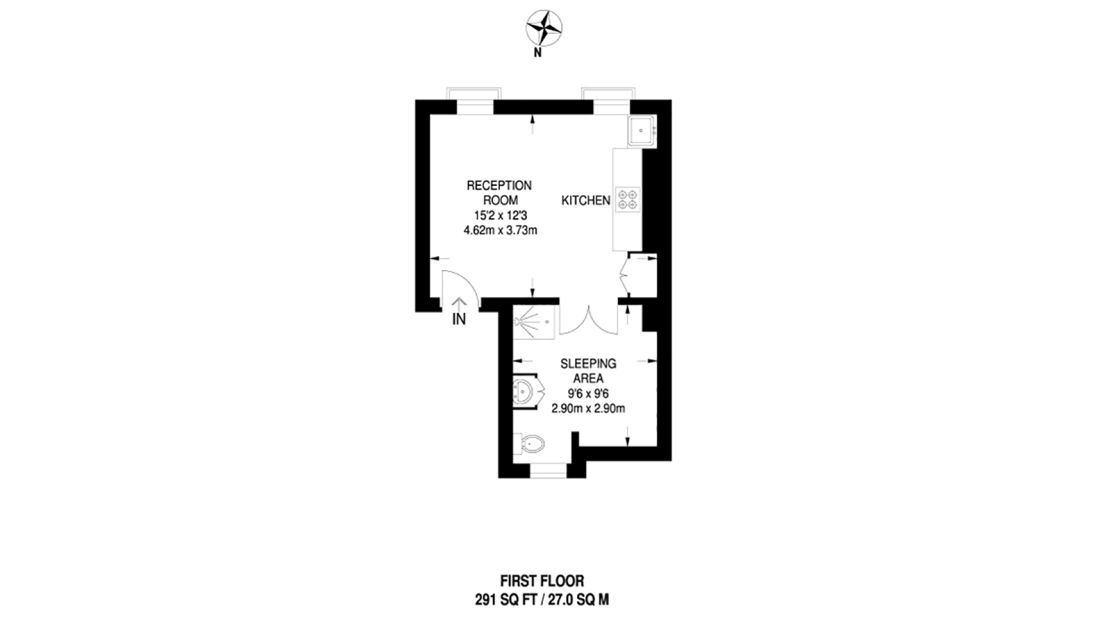

Flicking through the pictures, there are smart wooden floorboards, a Smeg oven and … Oh wait. Here’s the catch: The bed is in the bathroom.

Yes, if you were to roll out of bed you’d find yourself almost smacking into either the toilet or the basin.

And the asking price? £1,500 (US$1,940) per month for the 27-square-meter flat, according to estate agent Foxtons. CNN contacted the company – one of London’s leading realtors – but it declined to comment on the price or how much interest the ad had generated.

What’s most shocking, though, is that such a sizable price tag for a less-than-ideal living arrangement is by no means out of the ordinary in London’s rental market.

Experts say the British capital is experiencing a housing crisis. A shortage of affordable homes is pricing people out, impacting Londoners’ mental health, and – in extreme cases – driving up homelessness.

As in many major cities around the world, London is feeling the strain of changing demographics. Young people are moving into urban areas rather than out to suburbs, there’s an aging population to house, and an increase in single residents, according to analysts.

Meanwhile, wages haven’t kept up with rent increases, and the price of land for building new homes has leapt.

All of which has created a “perfect storm,” said Paul Hackett, director of London think tank the Smith Institute, whose research includes housing policy in both the UK and Europe.

Elsewhere in Europe, Berlin renters are also feeling the squeeze. But in stark contrast to London, the German capital has implemented a drastic new measure to halt skyrocketing prices.

‘We don’t want to end up like London’

This week, Berlin became the first city in Germany to freeze rent prices for the next five years. The price cap will affect around 1.5 million rented homes – 90% of all rental households in the capital, Berlin’s Department for Urban Development and Housing told CNN.

The cap doesn’t apply to social housing or homes built from 2014 onwards.

Unlike London, where 62% of people own their own homes, Berlin has long been a city of renters. Its large, empty buildings and traditionally cheap prices have long attracted arty types from across the continent. It’s not unusual for a Berlin family to live their entire lives in a rented home.

But in recent years the city has faced rapid price hikes, prompting mass protests from angry tenants.

While the rent freeze is a win for activists, it was opposed by many in the real estate industry and Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrat party, who warned it would likely deter urgently-needed construction work and modernization.

Some German politicians are adamant about what kind of city they don’t want Berlin to turn into. “We don’t want to end up like London,” finance minister Olaf Scholz told local media as he threw his support behind the proposed rent freeze last year.

Scholz described the horror of a British capital “where even lawyers and doctors have to live with flatmates, because they can’t afford their own apartment.”

Just over a quarter of Londoners – around 2.4 million people – rent privately. And they’re spending an average 37% of their income doing so, a spokesman from the Mayor of London’s office told CNN.

The knock-on effects of paying “ridiculous amounts of money” on rent mean that in some cases, “people are not having children,” said Hackett. They’re “getting stressed,” have “less time to spend with their loved ones,” and “less money available to go on holidays.”

At the more extreme end of the problem, there is the prospect of “homelessness, overcrowding, and council-run temporary accommodation,” he added.

Rent controls in London?

So could a Berlin-style price cap happen in London? The city’s Labour Mayor, Sadiq Khan, seems to think so in his blueprint for reforming the rental sector.

However, it’s unlikely to become a reality any time soon, as the Mayor of London does not have statutory powers to implement such a cap. That’s decided by the national government, currently Boris Johnson’s Conservatives, which largely rejects rent controls on the basis that they deter investors.

It’s a view shared by Britain’s National Landlord Association. “Rent controls don’t work,” said spokeswoman Meera Chindooroy. “Because landlords are disincentivized to invest in the market.”

She added that under rent controls, landlords might not have the money available to improve their properties. There is also the risk of a “gray market” – landlords finding ways to get around the rent controls – Chindooroy said.

But this argument doesn’t wash with Dan Williams Craw, director of campaign group Generation Rent. “Landlords have a legal requirement to keep properties to a certain standard, and that wouldn’t change under a rent control system,” he said.

He added that currently landlords may actually “evade their responsibilities” to fix up properties, because if a tenant asks for improvements the owner “can turn around and say: ‘If I do that, your rent is going up.’” Craw said.

Since the 2016 Brexit referendum, skyrocketing rental prices in London have cooled, largely due to falling demand from EU migrants, said the NLA’s Chindooroy.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean prices will keep going down, said campaigner Craw. He questioned whether tighter immigration rules could impact construction workers coming to London from European countries – currently more than a quarter of the workforce.

Paying for a ‘massive junkyard’

As plenty of people house hunting in London recently will tell you, it can be a disheartening experience.

Almost a quarter of privately rented homes in the British capital fail the Government’s Decent Home Standard, according to the Greater London Authority (GLA).

The GLA said housing laws were not being adequately enforced by local councils, with thousands of homes plagued by exposed wiring, broken boilers and black mold.

It’s a grim scene that 35-year-old freelance photographer, Maja Smiejkowska, knows well. She moved to London from Poland 10 years ago, and has rented rooms in various shared houses in southeast London.

After living in her last place for five years, she said she knew it was time to move when the landlord refused to address a rodent problem, black mold in the bathroom, and a broken oven.

The last straw came when he announced plans to subdivide the house, creating two new bedrooms to shoehorn in additional tenants.

Smiejkowska said she already spends around 40% of her income on rent, and simply can’t afford to live by herself.

During her three-month house hunt, she came across places where eight people were living in five-bedroom homes, houses with no living room, walls “almost black from dirt” and the landlord’s possessions in every room.

“The whole garden was a massive junkyard for his belongings,” she said of one house. “I would have been paying £600 ($780) a month for his storage.”

Eventually Smiejkowska found a suitable five-bedroom sharehouse in the borough of Lewisham. But she doesn’t see herself living in London forever, given that she is unlikely ever to be able to afford a place of her own.

Among the cities Smiejkowska is considering moving to is – you’ve guessed it – Berlin.

“The rent is more affordable compared to what you’re earning,” she said, despite calling London “home” for a decade.