Editor’s Note: Haley Draznin is an Emmy-nominated reporter and producer for CNN. She works on the daily CNN Newsroom show and launched the CNN Business series “Boss Files.” Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @haleydraz. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely her own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

Before my grandmother was put on a train and taken to Auschwitz, she was alone in an empty apartment, as a teenager in Nazi-occupied Poland after she saw her family reduced by disease and persecution. Today, nearly 80 years later, she finds herself alone again in an apartment, unable to leave for fear of being exposed to the Covid-19 virus.

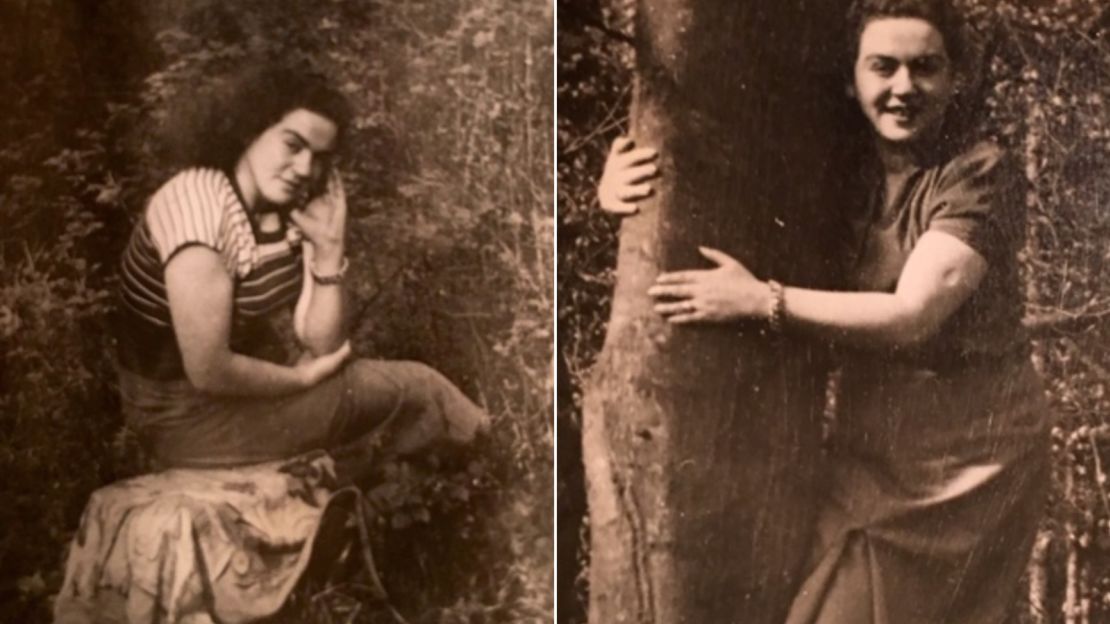

Her name is Genia Draznin. But I call her Bubbe, the Yiddish word for grandmother. At 97 years old, she’s sharp witted with a sense of humor. She’s like a Polish Zsa Zsa Gábor. Her porcelain skin and blonde hair compliment her social, flirtatious persona. Even after living in the United States for more than 65 years, she speaks with a thick accent.

Bubbe is tough as nails. She won’t let you leave the dinner table unless your plate is clean, but will always remind you if you look a pound or two overweight. She loves to talk and won’t let you speak over her, so I often find myself screaming into my phone just so she can hear me.

Every day she tunes in to watch the news and can tell you the top headlines. So, she understands what’s happening right now, recognizes the state of emergency around the world, and she’s scared.

“I want to live as long as my mind is working, but I don’t know what is going to be with the virus,” she told me on one of our daily phone calls.

The stay-at-home order is more than simply locking her door from the spread of Covid-19. But it has awakened her fears of uncertainty and loneliness from decades ago, emotions she has rarely felt since she was a young girl during that dark period.

“I feel very isolated,” she complains. “I am seeing no people at all. I cannot go downstairs. I don’t know, sometimes I feel that it is going to be the end of me.”

It has been 75 years since the liberation of Auschwitz, the biggest Nazi concentration camp, and the Holocaust ended. On April 20, the Jewish calendar marks Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, a day when the world pauses to remember the 6 million Jews who died and the millions more who lived on.

Never forget. It’s the responsibility of the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren to keep their memories alive. And that’s what I am driven to do.

We remember the Holocaust because of our hope that the world will never go through darkness as deep as that.

Of course, the lives we lead now because of social distancing guidelines are nothing compared to what people went through in the Holocaust, but the isolation caused by the health crisis can take a serious emotional toll. The lack of togetherness we are forced to adhere to is certainly felt, especially during the recent Passover Seder.

“I haven’t left the apartment in maybe four or five weeks,” Bubbe told me. “I’m pushing and trying that God will give me another year or something.”

Growing up as the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, I am compelled to listen closely and share their stories.

“I have nightmares almost every night. I see my mother and sister,” she said. “But I wake up and life goes on. When I hear your voice, I feel much better.”

There are about 400,000 Holocaust survivors still alive, with 85,000 living in the US, according to the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany.

For Auschwitz survivors like my Bubbe, the amount of survivors are fewer than 2,000.

Holocaust survivors are among the most vulnerable to the coronavirus. Many suffered from illness, malnutrition, mental health and other deprivations in their youth, factors which continue to affect them today.

“I fell a few weeks ago and I will never be the same. I was thinking to go to a doctor or to do something, but I think I will have more pain if I leave the apartment because of the virus,” she told me.

Millions of dollars are being poured into social service agencies around the world that provide aid to Holocaust survivors. Just last week, the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany announced $4.3 million in initial funding, “which may be increased as needed, will be available to many of the Claims Conference grantees around the world that already provide life-saving services to 120,000 Holocaust survivors.”

Each week my Bubbe gets food delivered from the Jewish Federation.

“My meals are simple. A little meat, some chicken, cereals, a few oranges, a dozen of eggs and milk,” she told me. “Enough to keep me from not going hungry.”

The psychological pain of the Holocaust still haunts her. Then, as now, there is fear of the unknown.

“I’m afraid to go to a hospital if I don’t feel well because I may never come out,” she said.

Renewed survival

She was born Genia Dichterman and grew up in Lodz, Poland, southwest of Warsaw, which was considered the second largest city in the Eastern European country before World War II. Her teenage years were forced into the Lodz Ghetto, where she lived in a crowded apartment with her parents, brothers, sister and niece.

She had several jobs in the ghetto years. She worked in a rope factory making straw shoes for German soldiers and recalls how her hands would become red and raw from the manufacturing. She also worked in a nearby farm within the ghetto. She has told me that job sustained her hunger during an era of malnourishment, as she would eat the potatoes and peas she picked in the field.

Within a year of ghetto living, her sister and niece became sick with typhus and died shortly after.

Her two brothers were able to escape the ghetto and were promised shelter, but after the war she learned they were deceived, betrayed and murdered when an acquaintance’s family revealed their Jewish identity to the Nazis. Her father was lured to a wartime job outside of the ghetto but never returned. Instead of a job he thought he may get, he was likely in an early transport to the concentration camps and swiftly murdered.

With her father and brothers gone, and the death of her sister and niece, my grandmother and her mother were hanging on by a thread. Her mother accepted a half-loaf of bread and cup of sugar that was given to her to leave the ghetto for “work” on July 7, 1944. That day is recorded with her name on a transport list to a concentration camp.

At nearly 20 years old, my Bubbe found herself alone in an empty apartment.

Bubbe’s life in Auschwitz: 1944 – 1945

Soon after her mother’s disappearance, the Lodz Ghetto was completely liquidated, and my grandmother was put on a train and taken to Auschwitz. She was deemed labor worthy and sent to a sub-camp of Buchenwald, a German concentration camp, where she was then placed in forced labor.

Her job was to transport munitions in the coldest months of winter. She had to use a wheelbarrow to bring heavy explosives and bombs to the train station which was over two miles away. Many girls died and were injured while doing this work when munitions exploded. Bubbe recalls that too often she was last to get soup and there was never any left after her long, cold and hard-slaving day.

As the war’s end neared, the Nazis rounded up the remaining Jews into freight cars, hoping American and allied bomb raids would finish them off. My grandmother was rescued by an unknown person and was saved while unconscious. She awoke to find herself in an abandoned home with bountiful food, and over a couple of days regained awareness.

She had made a firm promise to her father that after the war, if anyone were to survive, they would immediately return home to Lodz. With this message, she was determined to see her family again.

Alone, my grandmother spent many treacherous and dangerous weeks traveling, often on foot, the 250 miles across from outside of Berlin to Lodz.

Painfully, there was no one to greet my Bubbe when she arrived back home to Lodz. She learned she was all alone in the world, the sole survivor of her family.

Her Holocaust survival story is a testament to her strength, resilience and independence. And those traits again, at 97 years old, will allow her to persevere through the coronavirus pandemic.

Her hope, like that of us all, is that these “war-like” conditions will come to an end soon, and she can return to her family, who this time will all be waiting for her.

“Darling, I love you very much. Thank you for calling me. I will see you soon,” she says as she hangs up the phone.