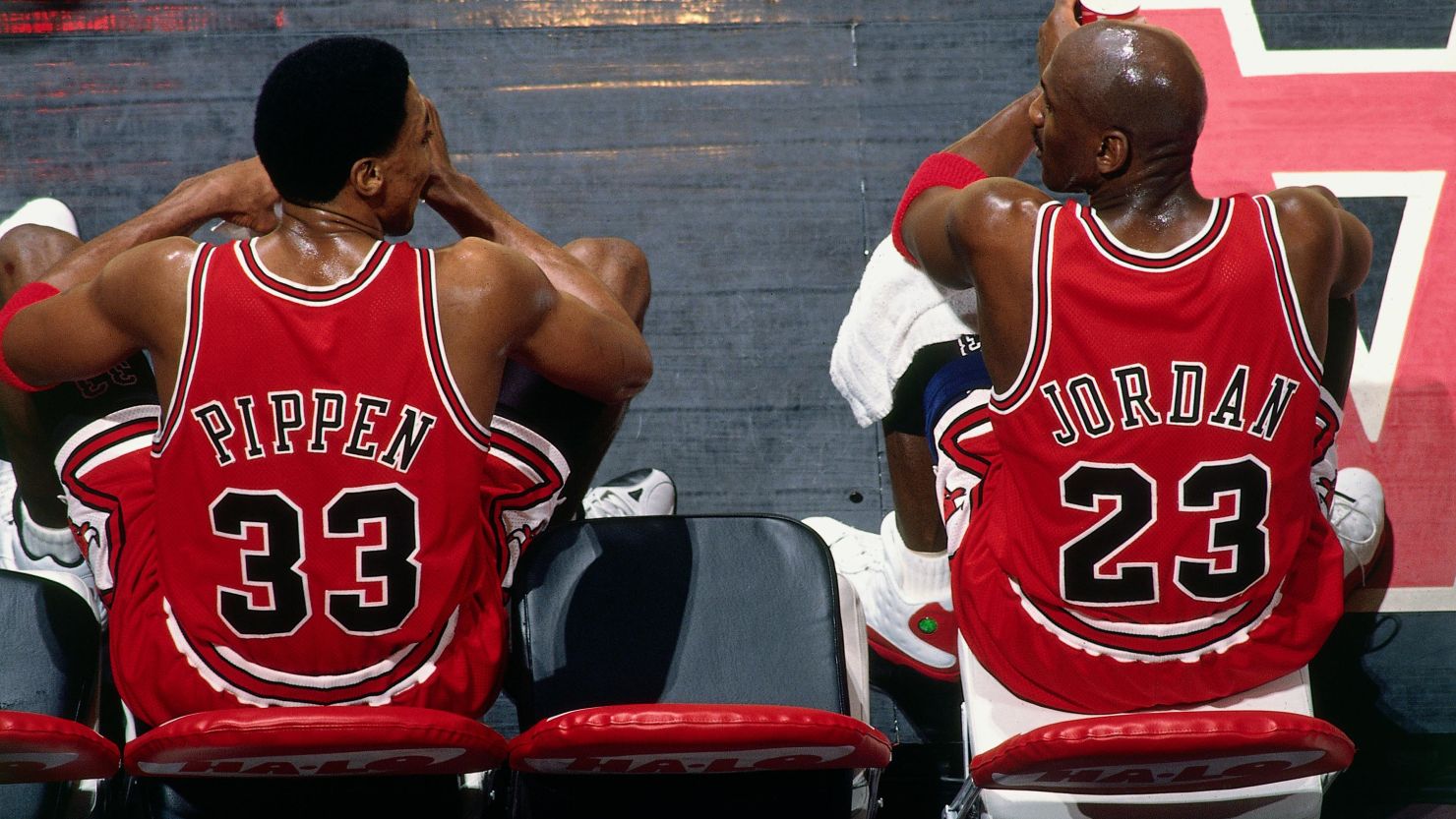

“Whenever they speak Michael Jordan, they should speak Scottie Pippen,” the basketball icon Michael “Air” Jordan says, reverently, of his former teammate in “The Last Dance,” the new 10-part docuseries from ESPN and Netflix about the 1997-98 Chicago Bulls season.

But while both men helped to catapult the once-middling Bulls to international renown – including, between 1991 and 1998, six NBA championships – Pippen’s experience with fame wasn’t as rosy as Jordan’s. The series’ second episode revisits some of the financial pressures that stalked Pippen early on in his career – pressures that, owing to enduring racial inequality in America, still affect young black players today.

In 1991, after the Bulls secured their first title in franchise history, Pippen, in his mid-20s, signed a five-year contract extension with the ascendant team. It was worth $18 million, which was good money – if you weren’t a colossal talent, as Pippen was.

“It was embarrassing because he was maybe the No. 2 player in the NBA,” former Bulls coach Phil Jackson says in “The Last Dance.” “His value was immense.”

Or as the team’s owner Jerry Reinsdorf puts it: “I said to Scottie the same thing I said to Michael: If I were you, I wouldn’t sign this contract. You may be selling yourself too short. It’s too long a contract you’re locking yourself in for.”

And yet, comments of this sort feel unfair at best. They pay virtually no attention to the constraints that shaped Pippen’s actions.

Read more from Brandon Tensley:

One of 12 children, Pippen grew up poor in the small southern city of Hamburg, Arkansas. By the time he was a teenager, his father had suffered a stroke and had to use a wheelchair; one of his brothers had been paralyzed by a classmate’s wrestling move. For Pippen, then, basketball wasn’t merely a pastime – it was a means of staving off financial precarity.

“I felt like I couldn’t afford to gamble myself getting injured and not being able to provide,” Pippen says in the series. “I needed to make sure that people in my corner were taken care of.”

The journalist Jemele Hill, who worked at ESPN for more than a decade, explained further why a young Pippen, already intimately familiar with the realities of the country’s racial wealth gap, would agree to something that in the long run wasn’t good for him.

“While not all black athletes in the NBA come from impoverished backgrounds, for the ones who do, it’s not as smooth a ride as you might think,” Hill told CNN. “Players often lean into their own understanding of things because it’s more comfortable than listening to the interlopers – the agents and other advisers – who are now in their world. … And for Pippen, looked at by his family as the one who made it, the years counted more than the money.”

“We don’t understand that poverty isn’t just a cycle. It’s traumatic,” Hill said, referring to the disorientation of sudden acclaim and wealth. “What Pippen wasn’t taught to think – because if you’re from his background, why would you be taught to think this? – was that he’d be a better player in a few years, and that’s why you don’t sign. He was thinking of all the bad things that might happen if he didn’t sign.”

In other words, when you add a bit of context, you see that there was a certain wisdom, not to mention heart, in Pippen’s decision.

But while the NBA has become more player-friendly since the ’90s – and for years has sought to steer rookies through the rocky waters of fandom – young black players who “make it” today often inherit the same professional and psychological challenges Pippen struggled with.

In fact, these difficulties are the subject of Starz’s “Survivor’s Remorse,” a sitcom that aired from 2014 to 2017. It follows a black basketball player who signs a big-bucks contract and moves from a down-and-out area of Boston to Atlanta; meanwhile, he must learn to deal with the unfamiliar solar system of celebrity.

Though fictional, “Survivor’s Remorse,” in key ways, mirrors the real-life journeys – full of the new stresses of wealth – of the Los Angeles Lakers’ LeBron “King” James (who was a teenager when he joined the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2003) and his manager and childhood friend Maverick Carter, both of whom were executive producers of the show.

“I have (survivor’s remorse) sometimes, because of my family and my neighborhood where I come from. There’s a lot of good people there, and not all of them, to use a phrase, make it out. And I did. But a lot of times I feel bad about making it when they didn’t,” Carter told The New York Times in 2014.

In this light, “The Last Dance” is more than just the story of a legendary basketball team. It’s a broader reminder that, in America, inequality touches everything – including sports.