Every Sunday since the coronavirus lockdown started, Stephanie Anstey drives 20 minutes from her home in Grottoes, Virginia, to sit in her school’s near-empty parking lot and type away on her laptop.

Anstey, a middle school history teacher, lives in a valley between two mountains, where the only available home internet option is a satellite connection. Her emails can take 30 seconds to load, only to quit mid-message. She can’t even open files on Google Drive, let alone upload lesson modules or get on a Zoom call with colleagues.

“You just have to plan,” Anstey said. “It’s not a Monday through Friday job anymore.”

So Anstey’s new office is in her car in the corner of the parking lot where the WiFi signal is strongest. She comes herewhen she needs to upload instructional videos, answer emails from students and parents or participate in the occasional video conferencing call. It’s not ideal, she says, but using her slow internet at home is even more frustrating.

Anstey’s predicament casts a new light on a longstanding digital divide that is being made even starker by the coronavirus pandemic.

More than 18 million Americans – about 5.6 percent of the US population – lack access to high-speed internet, according to the Federal Communications Commission. (Many technology experts dispute the agency’s figures – the company BroadbandNow says the real number is more than double that.)

Pockets of poor connectivity can be found in both small towns and cities, particularly in low-income urban areas. But those living in rural areas and tribal lands are especially likely to have slower speeds, spottier coverage and fewer internet service providers to choose from – forcing people like Anstey to travel to cafes, libraries and parking lots for a reliable connection.

And now that the pandemic is demanding most Americans do their jobs, complete schoolwork and access healthcare remotely, experts say the internet-access problem has become untenable.

“We are the country that created the internet. We think of ourselves as the most affluent nation on Earth,” said Christopher Mitchell, director of the Community Broadband Networks Initiative at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. “We should be embarrassed that millions of people have to drive to a closed library or a fast food restaurant in order to do their jobs or do their homework.”

For some people, the big issue is slow speeds

Building broadband networks, the best of which require installing fiber-optic cables underground, is expensive regardless of the locale, said Mitchell, whose organization advocates for local solutions in improving broadband infrastructure.

But fewer people in rural areas means fewer potential customers, giving publicly traded companies a lower return on investment. With less incentive to improve infrastructure and scarce competition, these companies leave many rural residents with few, and outdated, options.

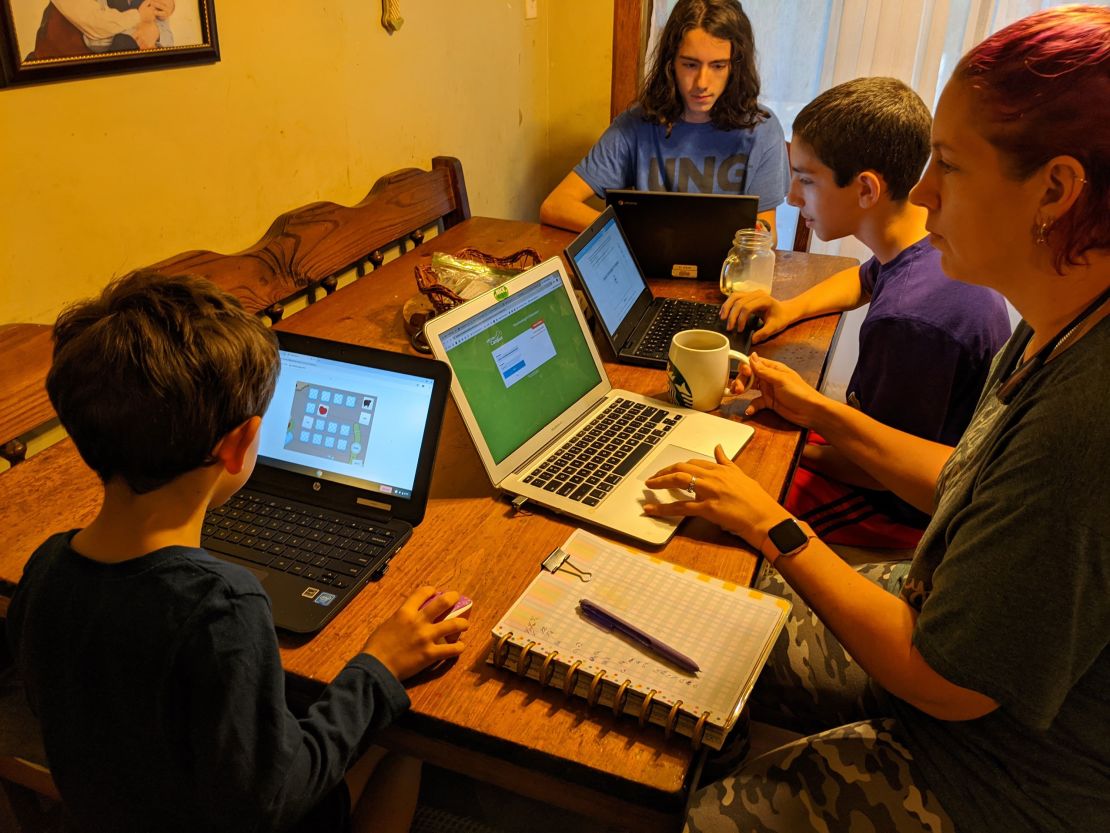

Addie Maiden, a seventh grade special-needs teacher in Dahlonega, Georgia, has DSL internet from a major telecoms company – the only provider available where she lives, she says. While the internet at home has always been slow, now she and her three sons – ages 15, 13 and 5 – are having to share already limited bandwidth as they try to work and learn from home.

Recently, the Maidens’ internet service provider has been offering a faster, hybrid fiber-DSL connection in Dahlonega, but the family has the misfortune of living about 100 yards outside the eligible area. That means they have no choice but to continue using DSL.

When internet service relies on DSL networks, there are bound to be problems, said Chip Strange, chief strategy officer at Ookla, the company behind Speedtest.net.

DSL, which transmits data over copper telephone lines, is a step above dial-up internet, though it’s still slower than other high-speed options such as cable and fiber-optic internet. For many rural households that use DSL, the speeds don’t even qualify as broadband.

The FCC defines high-speed internet as having minimum speeds of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) for downloads and 3 mbps for uploads. To put that into context, it takes a minimum of 1 Mbps to check email and social media, 3-4 Mbps to watch Netflix in standard definition and 25 Mbps to work from home, per the FCC’s guidelines.

And that’s just for a single person on one device. Take into account that multiple people in a household are now having to use high-demand functions at the same time, and it’s clear that many Americans aren’t getting the service they need.

Maiden said her current plan offers download speeds of up to 6 Mbps, though she’s looking into upgrading soon.

To make things work, her family disconnects the TV from the internet and turn off the WiFi on their phones. That way two people in the family – three, on a good day – can do their work at the same time.

Still, it’s a hassle.

“It would be nice if we could all get our work done at the same time so that it wasn’t staggered throughout the day,” Maiden said. “But we make do and I’m thankful at least we have internet to do it on.”

For others, it’s unstable connections

The internet infrastructure that does exist in many rural areas has been poorly maintained, making already slow connections unreliable, Mitchell said.

Often, the insulation surrounding the copper wires that DSL and cable networks use to transmit signals is worn out. In some cases, the wires themselves need replacing. Storms and rainy weather can interfere with the signals even more, resulting in a spotty connection.

That’s what Beatrix Gates has found in Brooksville, Maine, which has experienced storms in recent weeks.

Gates says her DSL connection is the best available internet the town has to offer. But some days it doesn’t work that well.

Gates teaches creative writing for a Master of Fine Arts program at Goddard College, and is a writer and editor. Between critiquing students’ manuscripts, submitting her own pieces, writing references and teleconferencing, she needs the internet sometimes more than she would like. Lately, she’s found that her emails and submissions don’t always go through.

So Gates will drive to the town office in Brooksville, about 20 minutes round trip, or the library in the neighboring town of Blue Hill, about 40 minutes round trip. Before the pandemic, she would have gone inside to get work done. With everything closed, she fires up her laptop in the parking lot.

“That’s not that unusual,” Gates said, adding that her fellow residents are working from their cars in parking lots too. “Anyone who lives here would tell you the same thing.”

WiFi networks can sometimes extend 100 feet from a building or more, Mitchell says. So municipalities and community centers in rural areas around the country are trying to bridge the gap by turning their parking lots into WiFi hotspots. Libraries in rural Wisconsin are keeping their WiFi on 24/7 for residents to access from outside. A city in Florida is offering free WiFi in school parking lots. A church in rural Georgia has opened its WiFi, and parking lot, to students.

While such interim measures are critical for some families, advocates say they’re only a Band-Aid solution.

Some say the few available options are expensive

The lack of competition in many rural areas also means that companies can charge more for fewer services, another point of frustration for residents.

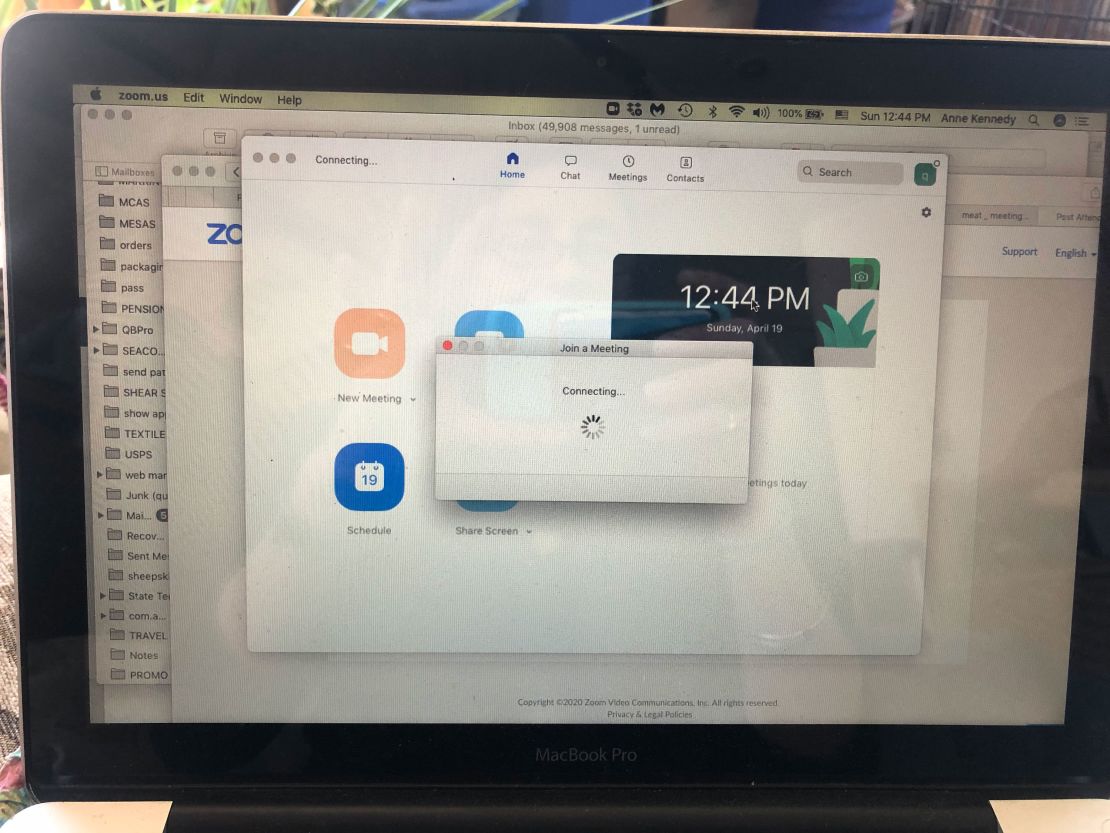

Nanne Kennedy, a farmer in Washington, Maine, says she earns most of her income through farmers’ markets and farm shows. During the pandemic farmers are being encouraged to shift their operations online.

Kennedy also serves as vice president of the Maine Sustainable Agriculture Society. With the pandemic affecting food distribution issues across the state, she’s having to join Zoom calls with industry leaders and other farmers.

“It’s really important that we stay connected and there’s a lot of work I’m trying to do to keep things moving and keep people getting the food products they’re working for,” she said.

All these tasks require technologies her current bandwidth can hardly handle, she added.

Kennedy said that her internet service provider has suggested she upgrade her plan to increase her bandwidth. But she’s already paying about $126 a month for an internet and landline bundle andfeels like she’s getting fewer services than her friends in other parts of the state.

Some families rely on mobile networks

Debbie Hill, who also lives in Grottoes, Virginia, said her area does have cable internet, but the plans are expensive. So she and her family – her 17-year-old daughter, her 11-year-old son and her husband – rely on a mobile hotspot through her cell phone carrier.

Hill and her husband both must report to work during the pandemic. She works the day shift at a food-packaging company, and he works the night shift at a box-making factory.

Their family typically reaches their high-speed data cap with about four or five days left in the month, after which the speeds are reduced until the next billing cycle.

More than 700 broadband and telephone service providers have pledged to maintain connectivity for customers whose lives have been disrupted by the pandemic. Companies are taking steps such as increasing internet speeds, lifting mobile data caps and offering free service for a certain period of time.

The Hill family, however, is still experiencing a data cap. And with both of the kids having to do schoolwork from home, that’s made things difficult when the end of the month approaches.

It was hard enough to get her 11-year-old son to sit still and do schoolwork on a laptop, Hill said. But then the instructional videos he had to watch started buffering more often and the photos he had to take for assignments started taking longer to upload. The issues made the situation unworkable.

Hill’s son has now opted for the paper packets the school district offers for those experiencing connectivity issues. She would rather he receive the dynamic instruction offered online, but in this moment, the written versions will just have to do.

“When you’re fighting an 11-year-old to do schoolwork on a computer when it’s lagging, Mommy loses,” she said.

It could take a while for things to improve

Leaders at the federal, state and local levels have been clamoring for years to expand broadband access. Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama both pushed for nationwide high-speed internet, with little success.

The pandemic has only amplified those calls.

The coronavirus stimulus package passed by Congress last month included hundreds of millions of dollars to expand telehealth services, improve library networks and provide loans and grants to expand broadband access in certain rural areas. President Donald Trump also tweeted recently that investments for broadband would be a part of the next round of relief discussions, though it’s unclear when or whether that would happen.

Even with emergency federal funds to address connectivity issues, many Americans with inadequate internet service likely won’t see any immediate improvements, said Strange of Ookla, the internet testing company.

The roots of the problem run deep, and addressing them will require efforts from state governments, nonprofit organizations and municipalities.

“There’s very little that a government agency can do during this tight timeframe to resolve this issue other than providing more access to existing services.” Strange said. “You’re not going to get networks improved necessarily during a time like this.”

That means that for now, millions of Americans will likely have to continue working in parking lots until the pandemic ends – and maybe even after that.