Editor’s Note: Marcus Mabry is the vice president of global programming for CNN digital. He covered the presidency of Nelson Mandela as the Africa bureau chief for Newsweek. He is the author of Twice as Good: Condoleezza Rice and Her Path to Power and White Bucks and Black-eyed Peas: Coming of Age Black in White America. The views in this commentary are his own. View more opinion columns at CNN.

Remember when “Black Lives Matter” was still considered a controversial thing to say?

On Friday, Roger Goodell, the commissioner of the National Football League responded to the demands of black NFL players and spoke out against racism. “We, the National Football League, admit we were wrong for not listening to NFL players earlier and encourage all to speak out and peacefully protest,” Goodell said. “We, the NFL, believe Black lives matter.”

It may be mind-boggling to think that that was once a controversial phrase. But it was, just two weeks ago.

What changed?

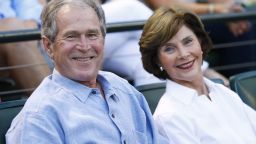

That’s what one of my 10-year-olds asked when I explained what all the press coverage was about. In the two weeks since George Floyd died at the hands of the Minneapolis police, white people have joined swelling protests across the country, demanding an end to systemic racism. Former President George W. Bush issued a statement acknowledging that white supremacy is alive and well in America, and we need to kill it. “The doctrine and habits of racial superiority, which once nearly split our country, still threaten our Union.” Symbols that have been the source of racial pain for generations and of intense debate for decades are suddenly being removed: Confederate statues, Confederate flags, and Sambo’s restaurant.

I told my son that I thought technology made a difference; now that there are cell phone videos of African Americans being senselessly killed by the police, more white people seem to believe it happens. People around the world have watched the graphic video that showed a white police officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck as Floyd said, “I can’t breathe.” Millions witnessed his body going limp as bystanders urged the police to stop pinning Floyd to the ground.

Floyd’s death was also just one in a string of several others. Ahmaud Arbery was killed while jogging in what his lawyer says is being investigated as a federal hate crime, Breonna Taylor, who would have been 27 on Friday, was an emergency medical technician killed in her own apartment in Louisville, Kentucky, by police officers executing a no-knock search warrant.

These devastating losses came off the back of a global pandemic, which disproportionally took black lives. African Americans and other marginalized communities suffer disproportionately from the health conditions that can make a Covid-19 diagnosis fatal and from longtime inequities in healthcare. George Floyd was also one of millions of people who lost their jobs in the economic upheaval caused by the virus.

Still, innocent black people have died at the hands of police before, and countless other videos have gone viral. Even my 10-year-old son, who knew these facts, seemed baffled by the white world suddenly awakening to his reality.

And that is the debate among African Americans: is this a paroxysm of outrage that will fade like so many social trends before it? Or is it really possible that we could be living through a moment of fundamental societal change?

As both former President Barack Obama and Rev. Al Sharpton have noted, things feel different this time around. Why?

White people now seem less inclined to debate whether there is racism in America, as the majority have for most of my life; they are demanding that it end. White people now seem less likely to question whether there is police brutality, as most have my entire life; they are simply demanding it end.

I’m reminded of South Africa in the years leading up to Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990 after serving 27 years. I also see glimmers of the American Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. The abuse of African Americans in the South and the outrage over it led to real change, including the end of Jim Crow and the disenfranchisement of black people, along with the extension of the rule of law to include all Americans.

But the mistreatment and murder of black people had been going on for nearly 200 years of American democracy and centuries before independence. What changed during the Civil Rights Movement was white people’s tolerance of this mistreatment. It was white outrage that led to change.

In the past week, every company that I have a relationship with has sent emails affirming their commitment to the fight against racism: that includes banks, software companies, children’s camps, and appliance stores. Everyone from homemakers to former presidents are saying white supremacy must end. People are marching in the great cities of the United States as well as the tiny towns. And protesters have shown their support from Sydney to Bratislava.

The changes in South Africa and the American South required a change of heart in white people. This new fight against racism will require the support of white people too. If our eyes and ears are to be believed, many are now stepping up to the plate and demanding it of themselves and their neighbors.

Will that demand for change be enduring? Will it sweep away inequities from the classroom to the boardroom to the newsroom?

The first time I told my twins the story of how the United States became a nation, they were five years old. As the three of us sat in a New York playground, I cried as I told them about a rabble of farmers and workers who took on the greatest empire in the world and, against all odds, won.

Years later, I told them the story of slavery. Later still I told them about Jim Crow. They know all that now. The son I was talking to about George Floyd had just finished a fifth-grade paper on the rule of law through US history. He had chosen as his topic sentence: “The rule of law, or equality before the law, is a part of our society; however it is a lie.” He handed in his final draft on May 28, three days after George Floyd had died.

It’s understandable that African Americans – some as young as 10 – are skeptical that our nation will live up to its promise of equality. These are not systems and institutions that are easily changed. And the trauma of 400 years of soul-destroying racism is not easily forgotten – some researchers believe it is imprinted in our very DNA. And we’re all too cognizant of the dashed promises of the past, from liberation to Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement.

But change does come. History teaches us that. It came to South Africa. It came to the American South.

Is this our moment? Dare we believe it?