Members of the ancient Irish elite practiced first-degree incest, archaeologists and geneticists analyzing genetic material from a series of Neolithic tombs have discovered.

Researchers found evidence of inbreeding in the genome of a man buried at Newgrange passage tomb, which was built more than 5,000 years ago, a team from Trinity College Dublin said in a press release.

This suggests the man belonged to a ruling elite that practiced first-degree incest – for example, brother-sister unions – in the same way as the pharaohs in ancient Egypt or Inca god-kings, the researchers said.

“I’d never seen anything like it,” said lead author Lara Cassidy, a geneticist from Trinity College.

“We all inherit two copies of the genome, one from our mother and one from our father; well, this individual’s copies were extremely similar, a tell-tale sign of close inbreeding. In fact, our analyses allowed us to confirm that his parents were first-degree relatives,” she said.

The full paper was published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The discovery was an “unexpected finding” and nobody had any idea about the practice in Neolithic Ireland, paper author Dan Bradley, professor of population genetics at Trinity, told CNN.

“We had no anticipation that it would be the case at Newgrange,” he said.

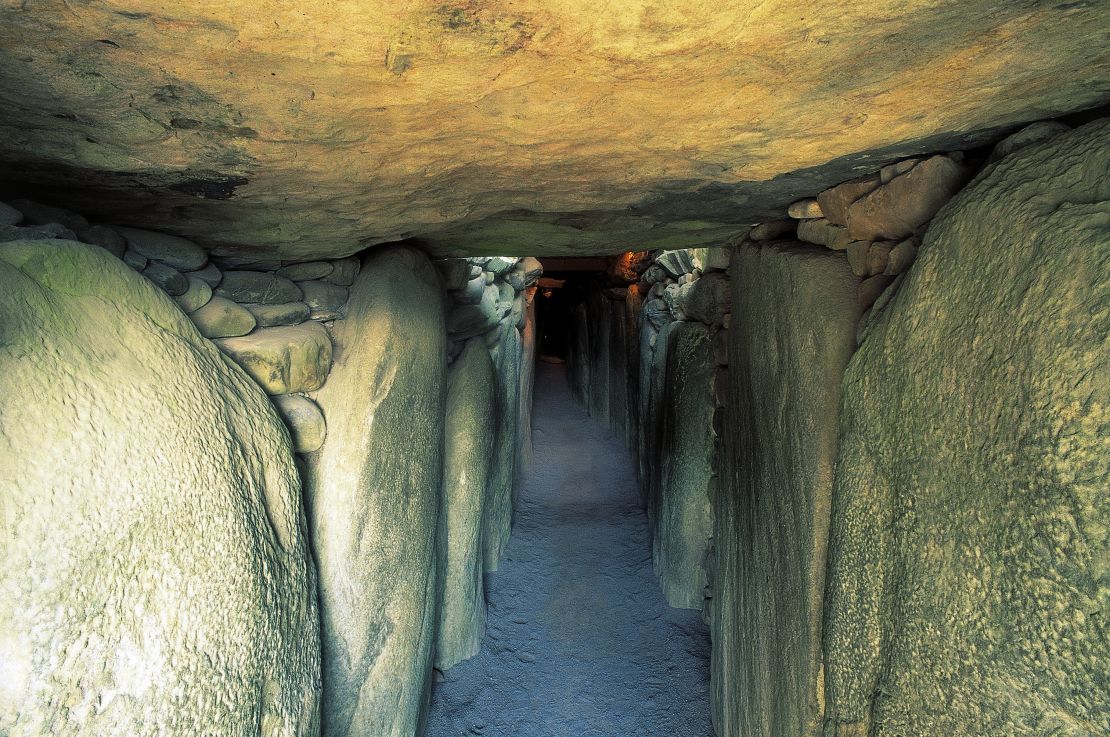

The man was part of a mysterious Neolithic society that built the Newgrange passage tomb in County Meath, eastern Ireland, which is known for the annual solar alignment that sees the sacred inner chamber illuminated by the winter solstice sunrise.

First-degree incest is a near-universal taboo, with the only confirmed social acceptances recorded among elites such as deified royal families, according to the researchers.

The practice is used to distinguish the elite from the rest of the population, reinforcing hierarchy and legitimizing their power.

It often combines with rituals and monumental architecture, such as the Newgrange passage tomb.

“The prestige of the burial makes this very likely a socially sanctioned union and speaks of a hierarchy so extreme that the only partners worthy of the elite were family members,” Bradley said in the press release.

The researchers also found genetic links between the man buried at Newgrange and other individuals buried in passage tombs such as Carrowmore and Carrowkeel in the west of the country.

“It seems what we have here is a powerful extended kin-group, who had access to elite burial sites in many regions of the island for at least half a millennium,” Cassidy added.

The findings also link to a local myth that tells of a builder-king who had sex with his sister in order to restart the daily solar cycle, Bradley said.

Another unusual discovery from the genome survey was the earliest diagnosed case of Down Syndrome, in a young boy buried 5,500 years ago at Poulnabrone portal tomb, the oldest known burial structure on the island of Ireland.

The team said this indicates that being visibly different did not bar people such as this infant from being given prestigious burials.

The researchers also found that the people who built these monumental tombs were early farmers who replaced hunter-gatherers when they migrated to Ireland.

However, Bradley said the small population of hunter-gatherers, who numbered just a few thousand, was swamped by the new arrivals, rather than exterminated.

Bradley said Trinity team were lucky to be able to sequence the genome of two hunter-gatherers, and found their genome marks them out from hunter-gatherers from Britain and continental Europe.

“They’re a bit more differentiated from Britain and the continent than Britain and the continent are from each other,” he said, which points to a prolonged period of isolation on the island at a time when Ireland was separated from Britain by a sea.