New fossil egg discoveries show early dinosaurs and marine reptiles laid soft-shell eggs like those of turtles, snakes and lizards and not the hard shells of bird eggs today, according to a new study.

Over time, dinosaurs likely evolved to lay hard-shelled eggs, according to the study which published Wednesday in the journal Nature. But the lack of eggs in the fossil record of some types of dinosaurs could be due to the fact that they were soft-shelled.

There are no definitive hard shelled dinosaur eggs from the early history of dinosaurs, according to the researchers.

In a second study also published Wednesday, a separate set of researchers reported on the first fossilized remains of an egg found in Antarctica in 2011, which they believe belonged to a now-extinct giant marine reptile. The odd, deflated-football shape revealed that it was also soft-shelled.

These two studies show how discoveries of eggs in the fossil record are changing the way researchers think about the way dinosaurs and ancient reptiles had offspring.

The evolution of dinosaur eggs

“The assumption has always been that the ancestral dinosaur egg was hard-shelled,” said Mark Norell, lead study author, chair and Macaulay Curator in the American Museum of Natural History’s division of paleontology, in a statement.

“Over the last 20 years, we’ve found dinosaur eggs around the world. But for the most part, they only represent three groups — theropod dinosaurs, which includes modern birds, advanced hadrosaurs like the duck-bill dinosaurs, and advanced sauropods, the long-necked dinosaurs.

“At the same time, we’ve found thousands of skeletal remains of ceratopsian dinosaurs, but almost none of their eggs. So why weren’t their eggs preserved? My guess — and what we ended up proving through this study — is that they were soft-shelled,” Norell said.

Norell and his fellow researchers conducted an analysis of eggs belonging to two very different dinosaurs. One was Protoceratops, an herbivorous dinosaur the size of a sheep that lived between 71 and 75 million years ago in present-day Mongolia. The other was Mussaurus, a long-necked herbivorous dinosaur that lived between 208.5 and 227 million years ago in Argentina.

They found at least 12 eggs and embryos that belonged to Protoceratops, and six of them included nearly complete skeletons. Most of the embryo skeletons were flexed, indicating their position while growing inside the egg. They had a “diffuse black-and-white egg-shaped halo” that obscured part of the skeleton. Two of the Protoceratops that had already hatched didn’t include this mineral halo.

Under a microscope, the halos resembled a protein-heavy eggshell membrane that has been found as the innermost layer of crocodile and bird eggs. Birds, mammals and reptiles called amniotes produce eggs that include an amnion, or inner membrane, that keeps the embryo inside from drying out.

The same thing applied to the Mussaurus egg. They compared this with eggshell data from lizards, crocodiles, birds and turtles and found that the dinosaur eggs were likely once leathery and soft. The eggs would have been similar to turtle eggs.

This is surprising because crocodiles and birds, which have hard-shelled eggs, are considered to be “living dinosaurs.” So this suggests that non-avian dinosaurs had soft-shelled eggs.

Using their data of the chemical and mechanical properties of these eggs, compared with eggshells belonging to 112 extinct and living relatives of dinosaurs, the researchers created an analytical tree to see how these eggs evolved over time.

They believed that protective hard-shelled eggs evolved from soft-shelled eggs independently at least three times over the time of the dinosaurs. The soft-shelled eggs were likely buried in sand or soil while plant matter helped incubate them. At most, the parent dinosaurs guarded the nest. This is similar to how some reptiles lay and hatch eggs today.

“From an evolutionary perspective, this makes much more sense than previous hypotheses, since we’ve known for a while that the ancestral egg of all amniotes was soft,” said Matteo Fabbri, study coauthor and a graduate student at Yale University’s department of geology and geophysics, in a statement.

“From our study, we can also now say that the earliest archosaurs — the group that includes dinosaurs, crocodiles, and pterosaurs — had soft eggs. Up to this point, people just got stuck using the extant archosaurs — crocodiles and birds — to understand dinosaurs,” Fabbri said.

The first fossil egg found in Antarctica

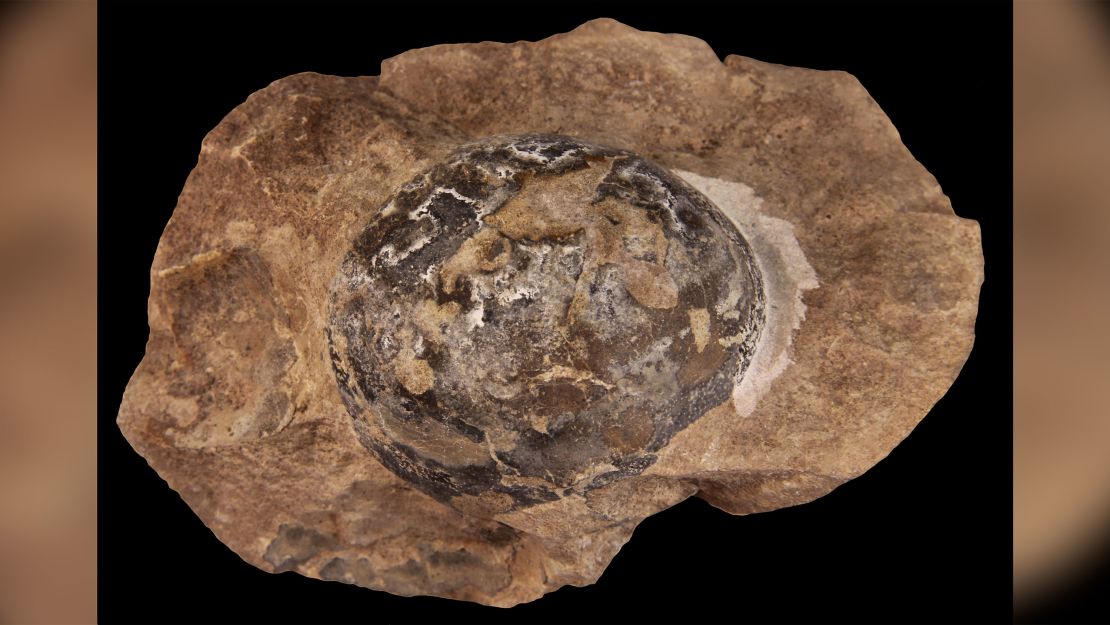

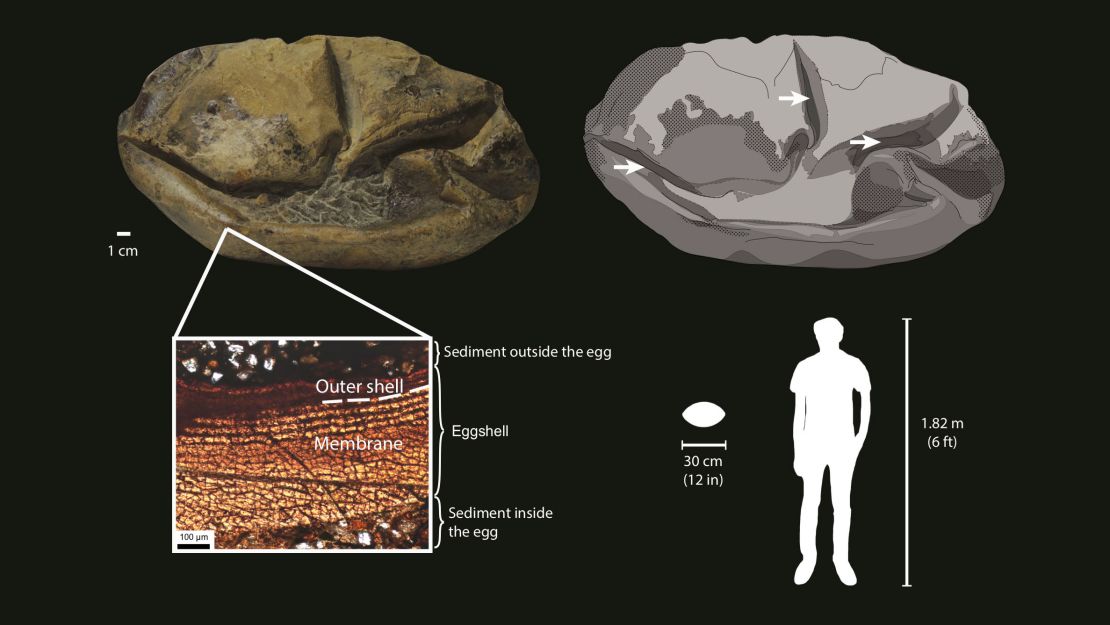

Soft-shell eggs rarely leave behind evidence because they don’t really fossilize — so researchers thought. But then they found something they nicknamed “The Thing” in Antarctica in 2011. It looked like a deflated American football, the researchers said.

It was found in a rock formation on Seymour Island, off the coast of Antarctica, by a team of Chilean researchers during an Antarctic scientific expedition funded and organized by the government of Chile.

The egg was brought back to the National Museum of Natural History, Santiago, and is now part of its collections, said Lucas Legendre, lead study author and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences.

For almost a decade, it sat in the museum’s collections without being labeled or studied. But a new analysis by researchers has determined that it’s a giant soft-shell egg from 66 million years ago. It’s the largest soft-shell egg ever discovered and claims the title of second-largest egg belonging to any known animal — behind the extinct elephant bird.

The egg measures more than 11 inches by 7 inches, and it’s the first fossil egg found in Antarctica. The study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

It’s comparable to eggs laid by snakes and lizards today that are nearly transparent and hatch very quickly.

But what could have an egg this large? There was nothing left inside the egg, like skeletal remains, to prove what kind of animal was once inside of it.

The researchers compared the body sizes of 259 modern reptiles to the sizes of their eggs. In order to lay an egg like this, the creature would need to be more than 200 feet long from snout to the end of its body — not including the tail.

“It is from an animal the size of a large dinosaur, but it is completely unlike a dinosaur egg,” Legendre said. “It is most similar to the eggs of lizards and snakes, but it is from a truly giant relative of these animals.”

Out of all the potential parents, they narrowed in on an ancient marine reptile like mosasaurs. It helped that fossil evidence of baby mosasaurs, plesiosaurs and their adult counterparts were found in the same rock formation.

“Many authors have hypothesized that this was sort of a nursery site with shallow protected water, a cove environment where the young ones would have had a quiet setting to grow up,” Legendre said.

Previously, it was believed that mosasaurs had live birth, said Julia Clarke, study coauthor and professor in the University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School’s department of geological sciences. This discovery completely shifts that theory.

“It shows their reproductive mode may have been very similar to that seen in some living lizards and snakes where there is a very thin eggshell present on an egg from which the baby emerges almost immediately,” Clarke said.

As for how this giant reptile laid eggs, the researchers have two different ideas.

Like sea snakes, it could have laid the eggs in the water, which then hatched quickly. Or, it could have left eggs on the beach. Once hatched, the baby mosasaurs would make their way to the ocean — not unlike baby sea turtles.

But giant marine reptiles were so heavy that they wouldn’t have been able to move on land. However, they could have maneuvered their tails on shore as the majority of their bodies stayed in the water.

“We can’t exclude the idea that they shoved their tail end up on shore because nothing like this has ever been discovered,” Clarke said.

The researchers want to return to Antarctica to find new fossils and collect more data.

“There are more and more studies showing that egg structure in reptiles was way more variable than previously thought,” Legendre said. “We are currently expanding our dataset to better understand the evolution of those eggs in reptiles as a whole.”

“These fossils that really change our thinking about all of lifestyles of extinct animals,” Clarke added.