The video showed a police officer from Austin, Texas, yanking a Black elementary school teacher out of her car and slamming her to the ground for an alleged speeding violation.

The dashboard-cam footage went viral in 2016, and local activists that year demanded the officer be fired. When it didn’t happen, Austin police reformers clamored for stronger oversight of the police, and rejoiced when the city unveiled a beefed-up independent watchdog office in 2018.

Called the Office of Police Oversight, the new city department operates independently of the police department and aims to not only hold individual officers accountable, but also make policy recommendations that focus on systemic issues, such as racial profiling. Even so, it hasn’t been enough to eliminate the types of incidents that result in allegations of police brutality and racial bias.

Since the city began revamping its oversight arm in January of 2018, Austin police have tased a Black man on his knees with his hands in the air; fatally shot an unarmed Black man in his car in a parking lot; and fired “less-lethal” bean-bag projectiles into the crowd at rallies honoring George Floyd – sending a 16-year-old Latino boy and a 20-year-old Black college student to the hospital with head injuries, the latter a skull fracture.

“There is so much work left to do,” said Austin City Council member Greg Casar, who is a vocal advocate of stronger police reforms. “Policy change alone isn’t going to solely do the trick. We need a culture change within policing.”

In addition to touching off a worldwide movement, the police killing of Floyd in Minneapolis has provoked a flurry of interest in police accountability, which often takes the form of police oversight agencies.

In recent weeks, at least a dozen cities have reached out to the National Association for Civilian Oversight of Law Enforcement (NACOLE) to either launch some form of new oversight agency or expand on existing ones, said its director of operations, Liana Perez.

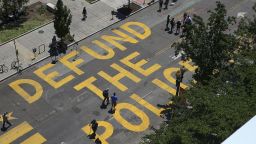

But at a time when “defund the police” has become a rallying cry for some activists, the notion of an oversight agency holds little appeal for those who want fundamental change.

Even the strongest proponents of the civilian oversight model say it, alone, isn’t enough to reform policing in America.

“This whole discussion is about policy and culture,” said Robin Kniech, a City Council member in Denver, whose system of oversight has been praised as a model by experts. “You can have a great use-of-force policy, but if you have a culture of impunity, it doesn’t work.”

Craig Futterman, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, said civilian police watchdogs can – in theory – be effective. However, he said, most of them are hamstrung by a lack or shortage of four things: independence from police departments or city hall, transparency, funding and authority.

“The answer to me isn’t that there is something fundamentally wrong with the premise of civilian oversight,” he said. “The problem is, in America we still have not really tried.”

Watchdogs are few and their authority runs the gamut

About 165 of the nation’s 18,000 police departments are subject to some form of police oversight – meaning the vast majority of law enforcement agencies across America are left to police themselves, said Perez of NACOLE.

They come in a dizzying constellation of formats with varying levels of authority, but in general consist of either appointed volunteers or paid non-law enforcement professionals who are tapped to police the police.

Usually, the bodies lack the power to impose discipline directly, acting instead as advisory panels for police chiefs, internal police department investigators or city managers. ?Some of the bigger agencies possess the authority to conduct their own investigations.

Their effectiveness – and power – runs the gamut.

In Los Angeles County, it was the FBI – not its civilian watchdog – that was investigating allegations of abuse of jail inmates at the hands of deputies that led to a coverup and criminal convictions of the former sheriff and some of his top officials.

In Inglewood – a city in Los Angeles County with a high rate of violent crime – the citizen oversight panel’s meetings have been canceled each month since June 2018, according to the city website. Emails from CNN asking the committee members about this dynamic were not returned, but a 2016 story in the Los Angeles Times quotes a city official saying the commission has “no authority” to “discuss or oversee or even hear any cases of [or] related to officer involved shootings.”

By contrast, one of the nation’s strongest civilian oversight boards is located in the northern half of California – the Oakland Police Commission.

This February, in an extremely rare move, the panel of civilian appointees voted unanimously to fire without cause Oakland’s police chief, who had clashed with the commission over police shootings and diversity on the force, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. Their action required mayoral approval, which was granted.

But the commission – which says it was founded to oversee policies in the wake of “a sex scandal involving multiple officers with a minor” in May 2016 – was dinged in an audit earlier this month for failing to review the department’s budget, comply with the state’s open meetings law and hire an inspector general, among other things.

In response, police commission Chair Regina Jackson said the “auditor’s criticisms fail to account for the full span of the commission’s work or the full scope of the commission’s authority.”

Tom Nolan, an associate professor at Emmanuel College in Boston, said Oakland is an outlier.

“It’s the only city that I’m aware of where it has a police review agency that actually has the authority to terminate the chief for cause, or to recommend to the mayor that the chief be terminated without cause,” he told CNN.

On the opposite coast, it was New York City’s Civilian Complaint Review Board – not the criminal courts – that brought discipline to the officer who placed a chokehold on Eric Garner, who died after uttering the words “I can’t breathe,” wrote the chair of the panel in a 2019 op-ed.

Although no criminal charges were filed against police officer Daniel Pantaleo, the review board – which has the power to investigate claims of wrongdoing, rather than merely review the investigations of internal affairs – acted as the prosecutor. Its findings were presented to an administrative judge, who made the recommendation that prompted the NYPD to terminate Pantaleo without pension.

The watchdog agency last week released all the prior complaints made against Pantaleo after the New York legislature – prompted by public outrage over George Floyd’s death – repealed a law that had shielded the disciplinary files of police officers from public disclosure.

Oversight not ‘the panacea many expected it to be’

Research reveals many police watchdogs remain largely toothless.

NACOLE recently completed a survey of civilian oversight agencies, including 54 that oversee municipal police departments, and provided the unpublished results to CNN.

Twenty-four said they didn’t have the power to issue subpoenas; for five others, their subpoena power excluded sworn officers.

Only two agencies, in Detroit and Chicago, said they had “the authority to implement or impose” new or revised police policies.

Twenty-one agencies said the departments they oversee weren’t even required to formally respond to the recommendations they made – let alone actually make any changes.

All but four of the agencies said that their access to information like use of force records, stop or search reports, body camera footage or personnel files “depends on the cooperation” of the police department they oversee.

“Civilian oversight has not proven to be ‘the panacea many expected it to be,’” wrote Stephen Rushin, a police accountability expert at Loyola University, in a 2017 report for Duke Law School.

Civilian oversight agencies have also been weakened by police unions.

In New Jersey last year, the Newark Fraternal Order of Police won a lawsuit that pulled the fangs out of a civilian review board, stripping it of its subpoena power to investigate complaints against police. The board won an appeal and the matter now is before the state Supreme Court, according to a recent report in the Center for Public Integrity.

Also in 2018, in Tennessee, the Nashville Fraternal Order of Police spent $500,000 on TV ads and other campaign activities calling on voters to oppose a charter amendment to form an oversight panel – a proposal prompted in part by the police killing of two Black men by White officers, according to the Tennessean. Despite the union’s efforts, the initiative prevailed.

What could make oversight more effective?

In recent years, the civilian board model has been losing ground to an emerging model of oversight that now makes up about a quarter of the nation’s oversight agencies, Perez said.

These are often referred to as “auditing” or “monitoring” agencies, and they are composed of paid staff – not appointed volunteers, Perez said. Many of the staffers are “monitors” who are lawyers by trade and report to the city manager.

The idea is to set expectations for officers on the front end, to better avoid disasters on the back end.

“Back ends don’t work without good front ends,” said Barry Friedman, a law professor and director of the Policing Project at New York University School of Law. “Policing desperately needs a front end.”

To that point, Denver has emerged as a model for effective police oversight.

Denver’s Office of the Independent Monitor is a city department with 15 employees – led by mayoral appointee Nicholas Mitchell – who weigh in on “back end” discipline cases and “front end” matters of policy. In late 2013, Mitchell, who like many of his employees is an attorney, uncovered a large backlog of civilian complaints in the sheriff’s department that included accusations by jail inmates that they’d been physically, sexually or verbally abused by deputies.

Kniech, the Denver City Council member, said this led to a series of reviews that culminated with a major structural change: removing the sheriff’s internal review arm and reestablishing it as an independent entity.

“Internal affairs are no longer internal,” said Kniech.

The union representing sheriff’s deputies told the Denver Post they believed the new division would just add unnecessary layers of bureaucracy.

“We’re just very disappointed in how this is going,” Mike Jackson, president of the union, told the newspaper.

Denver’s robust watchdog apparatus hasn’t been enough to change some of the more deeply rooted problems.

“We have not overcome the institutionalized racism that lives in individual officers and in the system,” Kniech said.

Kniech cited the 2015 case of Jessica “Jessie” Hernandez, age 17, who was sleeping in a car that was suspected stolen with four other teens. When police arrived and got out of their cars to talk to the teens, Hernandez, who was behind the wheel, started driving away. Officers fired four shots into the driver’s side window of the car, killing Hernandez.

“Rather than jumping out of the way of the car, the officer shot into the car” and killed Hernandez, she said.

The officers involved with the incident were cleared of criminal wrongdoing by the DA; the officer who shot into the car said he feared for his safety.

Hernandez’s parents later sued the city, which paid the family $1 million in a settlement.

Despite improvements, there’s still more work to do in Austin

Austin city officials boast that their new office of oversight is the strongest in Texas. But while it, like Denver, uses the monitoring and auditing approach, unlike Denver, Austin’s office lacks subpoena power.

It has, however, been credited for its transparency.

New rules enable citizens to file complaints anonymously and easily – by a phone call, for instance. Each complaint is prominently posted online, with the accused officer’s name redacted.

Complaints have skyrocketed. The George Floyd protest alone, in which Austin police fired “less-lethal” beanbag rounds into the crowd, generated more than 200, according to Farah Muscadin, head of Austin’s police oversight agency.

Austin Police Chief Brian Manley said in a Twitter post that officers on one occasion fired into the crowd after a demonstrator hurled a water bottle and bag at the police. He acknowledged that police accidentally hit another man, Justin Howell, a 20-year-old college student who suffered a skull fracture when a beanbag projectile hit the back of his head.

Chas Moore, a local activist who spearheaded the drive for revamping the oversight office, said the resulting reform, to date, has been “very, very, very incremental.”

“The APD has a very long way of going before they begin to regain trust in the communities that they harm the most, which is Black and other communities of color,” he said.

In December, Austin City Council voted unanimously to conduct an audit of the department for racism and bigotry.

Chief Manley, who did not respond to a CNN request for comment, has defended the department against such accusations.

Earlier this month, the City Council grilled him about whether the police response to the Floyd protest is a sign the department is in need of “institutional reform,” with one member pointing out that the police didn’t fire “less lethal” munitions on people protesting the coronavirus shutdown.

“I don’t believe that the occurrences of this weekend should lead people to believe automatically that there’s a culture problem,” he said, according to the local NPR affiliate.

To date, few of the complaints involving excessive use-of-force allegations have resulted in disciplinary action since the oversight office’s official launch in late 2018, said Muscadin, adding that she and the policing community typically don’t see eye-to-eye on use-of-force matters.

“We will watch the same video and see two different things,” said Muscadin, an attorney who, prior to relocating to Austin from Chicago for the position, worked as an assistant public defender for the Cook County Public Defender’s Office.

The office also released a racial profiling report showing that Austin police disproportionately pull over black motorists, who make up 8% of the population but constitute 15% of the stops. Muscadin has recommended a racial-profiling policy for the department, as well as a mandatory class on the history of race and policing.

Austin’s most high-profile open case involves the fatal police shooting in April of Michael Ramos, an unarmed Black man.

The oversight office and the police department are squabbling over how to release the body-cam footage, which shows Ramos getting back into his car in a parking lot of his apartment complex after being shot with a beanbag round. When he pulls the car forward, an officer fires live rounds into it, killing Ramos. The officer believed the vehicle at that point was a weapon, police said.

In late May – a few days after Floyd’s death – the district attorney announced that she would present the Ramos case to a grand jury.

Last summer, the same officer who killed Ramos – Christopher Taylor – was one of the officers involved in the fatal shooting of 46-year-old Mauris DeSilva, who had reportedly been holding a knife to his own throat in his apartment building. Police said DeSilva was experiencing a mental health crisis, and that he walked toward officers while still clutching the knife.

The case touched off an internal investigation, but nearly one year after the incident, all the evidence – including the body-cam footage – remains sealed from the public amid a civil lawsuit pitting DeSilva’s family against the city. (A police spokesperson told CNN the state attorney general has ordered the city to withhold the evidence pending the outcome of the district attorney’s review of the case.)

Ken Casaday, president of the Austin Police Association, said Taylor and the other officer “followed their training” with respect to the DeSilva case.

“That’s all we expect,” he told CNN, saying he is withholding judgment in Ramos case because the investigation is ongoing.

Meanwhile, Ramos’s mother, Brenda Ramos, who has demanded that the officer who killed her son be held accountable, continues to wait.

“I just miss him so much,” she said in a phone interview. “I’m hurting more and more, because that officer is working on the street after what he’s done.”