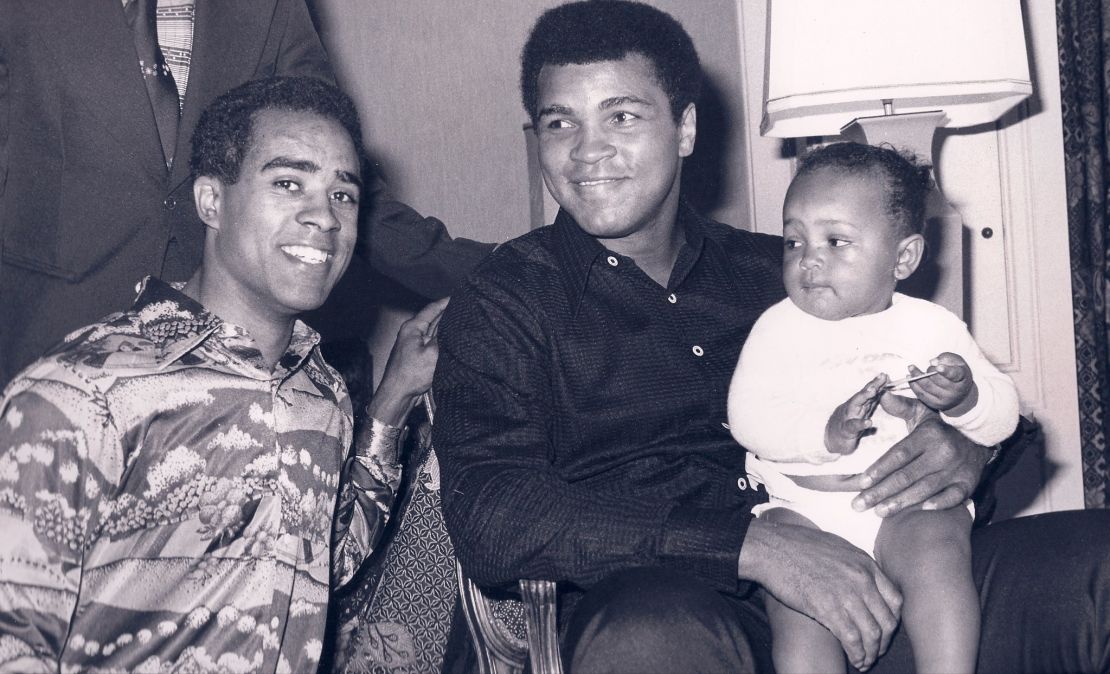

When Willy T. Ribbs speaks his words are packed with punch, power and purpose – verbally mimicking the actions of his sporting hero and former friend, Muhammad Ali.

They are words carved from the experiences of a man who knows what it’s like to stand alone.

A Black driver whose effort to break into motorsport was slowed by several hurdles and stereotyping throughout his career.

But for all the fighting talk his words are undercut with a sense of what could and perhaps should have been.

“I wanted to be like the greats – I wanted to be Formula 1 world champion. My mother always said I was 25 years ahead of my time.”

It was a dream conceived in the Californian mountains.

A dream that would be challenged by politics, personalities and prejudice – but one which would ultimately spark a series of trailblazing moments and in turn spawn motorsport’s original barrier-breaking pioneer.

‘We don’t really want you here’

Speaking from his ranch in Driftwood, Texas, a recurring word emerges throughout – “playbook.”

The “playbook” was Ribbs’ blueprint for success.

In childhood, his father – an amateur sports car racer – planted the motor racing seed.

In adulthood, Emerson Fittipaldi – who would go on to become a two-time Formula 1 Champion – provided a path for him to blossom.

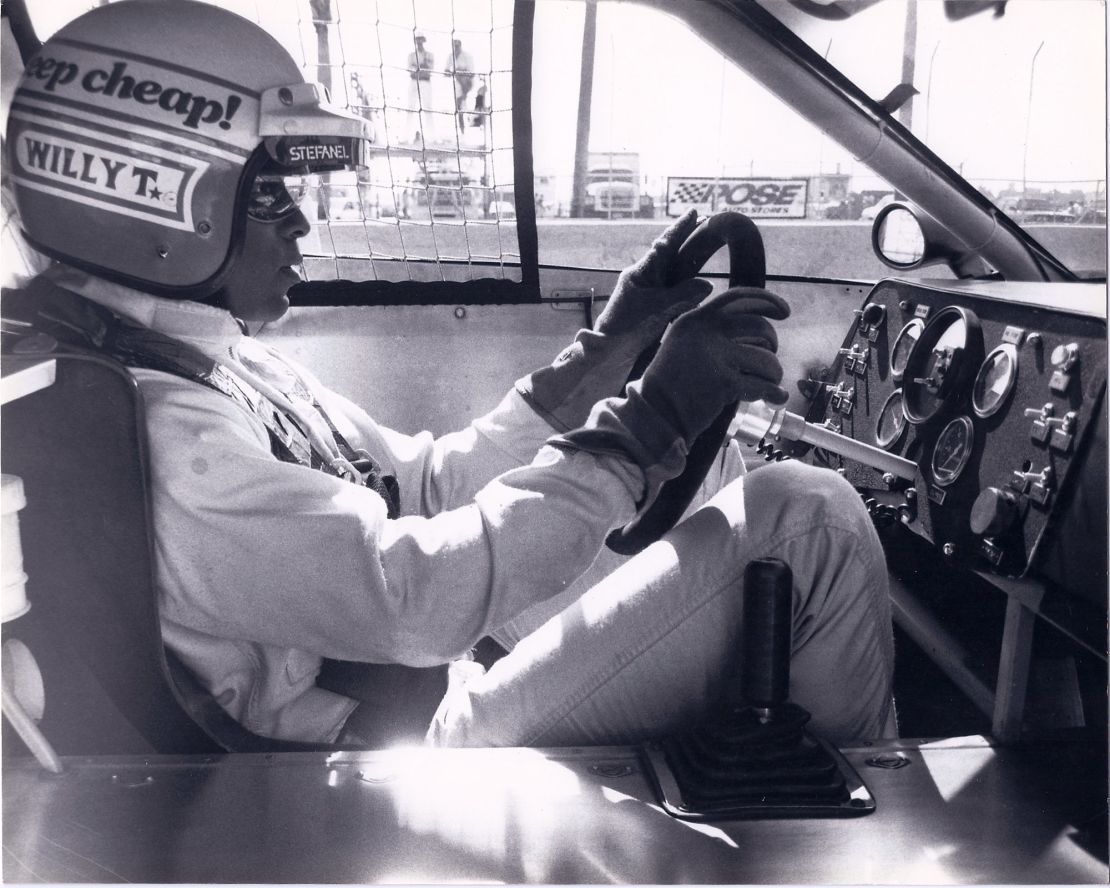

Like Fittipaldi, Ribbs’ early career took him to England to compete in the single-seater British Formula Ford Championship. He took to racing like a duck to water – winning six of eleven races and with it the “Star of Tomorrow” title in 1977.

“They saw Willy T. as a fast driver and a winning race driver,” Ribbs fondly recalls.

The following year he returned to the US with his sights set on competing in IndyCar – the contrast in reception in the pitlane, though, couldn’t have been greater.

But his reception in the pit lane at a NASCAR race was a shock.

“All it took was the N-word. When you get addressed by that name you know what it’s about,” he vividly remembers of his preparation to race at the Alabama International Motor Speedway in Talladega, Alabama.

“They made it clear: ‘We really don’t want you here. Why are coming to our sport? Can’t you play basketball or football?”

Humpy Wheeler, who at the time was president of Charlotte Motor Speedway, wanted to try to run Ribbs in NASCAR later that year – his effort, though, was in vain.

Ribbs was charged with a traffic violation in Charlotte – Wheeler had to bail him out of police custody. The next day, Wheeler and Ribbs went their separate ways.

Death threats followed, Ribbs says.

“I didn’t give a damn about it at all. I know one thing – You weren’t going to do it to my face. I considered it very exciting […] You got letters or a phone call. I would sort of invite it: ‘Okay, start killing.’”

NASCAR did not immediately respond to CNN’s request for comment about the way Ribbs says he had been treated by the sport.

One pioneer inspires another

It’s this bullishness, bravado and bravery that is captured in a single word emblazoned on the front of Ribbs’ hat – “UPPITY” – the title for a recent Netflix documentary charting his remarkable life story.

And yet it’s a word which represents much more – a racially charged term often aimed at Ribbs to imply he was acting above his station.

“They just thought I should walk 10 paces behind them. That wasn’t happening.”

“(For me) It wasn’t about color. It was about being a race driver. Race drivers have no color either you can get it on or you can’t.”

He eulogizes how Ali provided him with the “playbook” to fight the antagonism – not physically but mentally and emotionally.

“He had great principle, integrity, and he was strong. Mentally he was a very tough man [and] being around him, I learned resolve. What I needed to do to accomplish my goal.”

And accomplish that goal he did.

Ribbs took the Trans-Am series by storm from 1983-85, winning 17 times and establishing himself as the hottest property in sports car racing.

Fittingly his victory celebrations were not low-key. Returning to the pitlane and in an ode to Ali, he would perform the “Ali Shuffle” – feet moving back and forth in quick succession on the hood of his car and hands raised aloft.

His break came in April 1985 when, backed by boxing promoter Don King, he made his first attempt at qualifying for the famed Indy 500.

Mechanical problems ultimately doomed his bid. But a significant landmark was on the horizon – one that was to enshrine him in motorsport folklore.

‘He wanted me in Formula 1’

December 1985. Autódromo do Estoril, Portugal.

Approached by British businessman Bernie Ecclestone, who owned the Brabham team, Ribbs became the first Black driver to test drive a Formula 1 car.

“He wanted me in the car – He wanted me in Formula 1.”

It was both a symbolic yet finite moment – for it was to be as far as he would go in F1.

Brabham’s main sponsor at the time was Italian electronics manufacturer, Olivetti. Ribbs says the company wanted an Italian driver installed. There was no compromise – Italians Riccardo Patrese and Elio de Angelies were to be the drivers for the 1986 Formula 1 season.

“I have no issues with that,” says Ribbs. “I would’ve liked to have had a major multinational sponsor from the United States to support it but it didn’t happen […] My goal was to be in Formula 1 but Bernie had made a statement.”

The groundwork had been laid but it would, though, take another 21 years for a Black driver – Lewis Hamilton – to officially Formula 1.

But Ribbs’ feat would serve to fuel another piece of history.

After several attempts, six years later in May 1991, he qualified for the Indy 500 – becoming the first African American driver to do so.

He would complete five laps of the race before engine failure forced him out but it was unquestionably a significant barrier breaking moment.

Two years later, though, his luck came full circle as he competed again and finished all 200 laps.

And he’s keen to remember those owners who supported him throughout – including Jim Trueman and Dan Gurney.

Fight for equality

Yet almost 30 years on, the landscape is much the same as when Ribbs first broke ground.

In 2020, NASCAR’s top circuit has only one full-time Black driver – Bubba Wallace.

CNN’s interview comes in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and just a day after NASCAR announced it would ban Confederate flags from its events after a vocal campaign led by Wallace.

For some the decision is long-overdue. Ribbs, though, remains skeptical.

“When NASCAR refuses to let Confederate flags fly in their infield: Is that sincere? If George Floyd was alive right now, those flags would still be flying. That’s why I’m saying not much. They’ve got a lot more to do.”

NASCAR didn’t respond to CNN’s request for comment about Ribbs’ assertion.

NASCAR is not the only place where the battle for equality and diversity continues to be fought.

Formula 1 has acted to address its lack of representation and inclusion in the sport by setting up a task force and foundation, alongside its #WeRaceAsOne initiative.

Just as Ecclestone gave Ribbs his shot, Ribbs is quick to praise another “monumental” figure who gave Hamilton his opportunity in the sport – former McLaren CEO and founder, Ron Dennis.

“(He) put Lewis Hamilton in the position to be where he is today. He saw a great talent, mentored him and took Lewis right to the top.”

“Ron has already given everyone the playbook. Get the playbook from Ron.

“If you can put a man into space, this is a piece of cake. It’s not rocket science.”

Lewis ‘is the band leader’

In many ways Ribbs handed Hamilton his own “playbook” – he offered a glimpse into what could be achieved both on and off the track.

Yet pure talent was never enough. Racing necessitates backers and resources – And Ribbs largely never had that.

Hamilton, though, does – and he’s seizing the opportunity both as the dominant racer of his time and an advocate for change.

“(Lewis) is the band leader and he’s not afraid […] He’s broadened the sport worldwide to people of color [and] will be anointed as the greatest of all time in the end,” Ribbs proudly states.

“There’s always going to be that element (that) does not accept purely race […] Just like there’s a lot of people that won’t accept Lewis for race only.”

“They’re not just dumb. They’re scared. They’re cowards […] You don’t judge a man on his skin color. You don’t judge a man on his accent. He’s a man or he’s not a man.”