On Tuesday night, Aaron Fortner, a high school English teacher in Missoula, Montana, sat at his computer for nearly four hours watching a virtual meeting of Missoula County Public Schools’ board of trustees. Leaders listened as citizens weighed in against starting the school year in person.

“Out of 50 or 60 public comments, only one person supported in-person learning,” he said. “I was hopeful.”

Fortner hoped on behalf of the rattled teachers he advocated for as a member of the local teacher’s union. Those educators were afraid of coronavirus spreading rampantly in schools teeming with crowds of ebullient young people. Without tenure, many teachers didn’t feel confident about speaking out, he said. Nonetheless, the community appeared on their side, arguing for virtual classes.

But then the board voted overwhelmingly to support a hybrid model of both online and in-person learning, to be implemented when students return on August 26. His heart sank.

“I was just blown away,” he said. “It was a jaw-dropping moment after three and a half hours of public comment. It was an avalanche moment for our community.”

Teachers are in the crosshairs of the national reopening debate

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has issued guidelines explaining how schools can potentially return to in-person classes this fall if case counts are low enough. And the American Academy of Pediatrics has urged districts to return to in-person classes, citing potentially devastating social and emotional losses to children that could occur otherwise.

But Fortner is one of countless teachers across the country forced to decide between bringing home a paycheck for their family and potentially entering what feels like a microbial war zone every day, risking constant exposure to hundreds of other teachers and kids.

Fortner plans to keep teaching this year. However, he’s not sure how much he’d be able to accomplish teaching International Baccalaureate courses on novels and poetry to mask-clad students, while trying to monitor who in the back row might be holding back cough symptoms.

“My priorities will shift from self-actualization, learning and knowledge toward policing public health guidelines,” he said. “When anyone doesn’t have their basic needs met, they can’t learn and grow.”

Local school board decisions are affecting more than 50 million students enrolled in K through 12 education, according to US Census data. And the National Center for Education Statistics charts the number of US public school teachers at 3.5 million.

In a normal year, they’d be in classrooms this fall. During the pandemic, the picture is much more complicated.

Of the 15 biggest school districts in the United States, 13 have chosen to begin classes completely online as of August 6. Only Hawaii Public Schools chose a hybrid route, as did the rural Missoula County, in Montana. And New York City, once the US epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak, plans to offer a blended model of virtual and in-person learning, provided the city’s infection rate stays below 3%.

They hail from the big sky country of Montana, the fields of Iowa, the outskirts of our nation’s capital and the streets of Atlanta. America’s teachers are the foot soldiers in our ongoing war with a deadly pandemic.

And not all of them are willing to go along with their leadership’s decisions.

Jami and Drew Cole, two Oklahoma educators who’ve been married for 29 years, are shouldering the burden.

They are both immunocompromised. Jami Cole, who teaches fifth grade, has rheumatoid arthritis, while her husband, a high school art and media production instructor, has leukemia.

They take solace in the fact that their rural county has had significantly lower case counts so far than more densely populated areas of the country. But they keep a close eye on how the virus is spreading in their state.

“It does keep me up at night that we could be exposed anywhere,” Jami said. “That’s the reality that we’re living in a Covid world that I can walk out of my door and my neighbor could have it.”

As they prepare to return to their classrooms, they estimated they’ve spent $500 out of pocket for personal protective equipment and for innovative supplies to help maintain physical distancing. The stress is taking its toll, however.

“I’ve had some pretty severe breakdowns, just crying in my bathtub or crying in my bed like I’m not ready,” Jami said.

And her husband said he “wouldn’t have been brokenhearted” if the school system had held only virtual classes for the first nine weeks.

A young teacher resigns to keep her grandmother safe

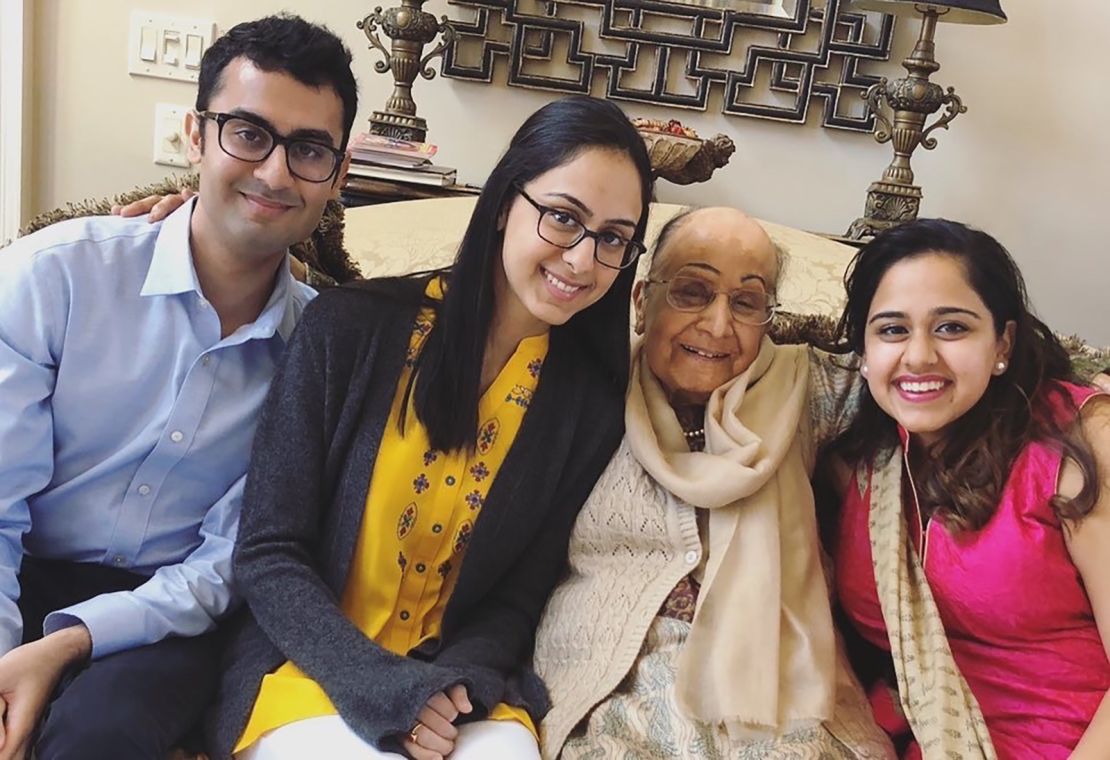

Ashima Gauba, is a 23-year-old Georgia Tech graduate and Teach for America corps member who spent the summer following the news and preparing for her second year of teaching computer science at Benjamin Banneker High School in Atlanta.

She lives with her parents, 26-year-old sister, brother-in-law and 84-year-old grandmother. Both Gauba and her sister are immunocompromised because of gut conditions, so the family orders all its groceries online and avoids contact with the outside world.

“If one of us is going to the dentist, they call ahead and wait in the car,” she said.

Over the summer, she started a petition to encourage Fulton County Schools to have a virtual start to the fall semester. The system did eventually opt toward starting online for the first few weeks but has plans to return to in-person classes.

Gauba took issue with several policies she saw in the employee handbook, including mask mandates for teachers but not students, and the fact there wasn’t a requirement for someone who tested positive to furnish evidence of a negative Covid-19 test before returning to school after two weeks of quarantine.

Given her family’s health needs, she felt as though the district’s precautions weren’t adequate. Not only did she want to quit: She was also willing to pay $1,000 to break her contract to be able to avoid crowds.

“It felt like neglect. It felt like my family is being undervalued. It felt like I was being undervalued,” she said. “It feels like your life or the life of people you love doesn’t matter in the grand scheme of things.”

Gauba resigned from her teaching job on July 29, announcing her decision on Instagram and Remind, a platform that teachers use to communicate with students.

“I had imagined that my students might be angry,” she said, recounting her emotions as she debated how to deliver the message. She had worried they would see her as choosing her family over them.

Instead she was met by heart emojis, well wishes toward her family and encouragement to “Stay safe, Ms. Gauba.”

“It was heartwarming and heartbreaking,” she said. “My students are more caring than many of our world leaders and school district officials are.”

This week she started a new job in which she can safely work from home, landing a program analyst role with Flockjay, a company that works to train groups traditionally underrepresented in tech and place them into tech sales roles at companies.

“It really feels like a continuation of what I was trying to do with teaching,” she said. “As my students get older, I want for them to be able to have the same opportunities in the tech industry.”

Making the best of it

More than 600 miles away in Riverdale, Maryland, Jeselle Percel has a considerably different outlook on the year.

“I’m excited to get back to the job I love so much and that I’m passionate about,” said the first grade teacher at Templeton Elementary School, just outside Washington, DC.

One reason for optimism is that her school has committed to strictly online learning this year.

That decision came following a survey of administrators, teachers and staff, in which a majority favored a virtual format.

“I was concerned because a lot of people think we can have … desks 6 feet apart, masks, gloves and reduced class sizes,” she said. “In practice, that would be very difficult at the elementary level.”

But in avoiding the risk of in-person teaching, Percel knows she has to tackle the socioeconomic divide that makes virtual learning incredibly difficult in a school district populated by a vibrant community of new immigrants to America.

She instructs kids from Central America, the Middle East and Africa, many of whom are in English as a Second Language courses and don’t have access to Wi-Fi at home.

Technology issues were a major hurdle for Percel last spring when her school abruptly pivoted online. Many of her students’ parents were frontline workers and couldn’t easily pick up laptops from the school for their children to use at home. And a rule of one laptop per family created problems teaching students who had other siblings attending the same school.

“There were all these obstacles to even begin learning,” she said.

Percel and her school district have had more time to prepare this year, but she knows her task teaching first graders online will be much more difficult than even in neighboring districts, where families are more affluent and can better endure the upheaval in work routines needed to supervise all the complexities of keeping kids connected and on task.

“It’s really important that leaders keep in mind students coming from low-income communities, who are disabled and who are still learning English,” she said. “The ones that I serve are left behind. Their needs haven’t been met in the current education system that America has.”

Two married teachers prepare totally different classroom designs

With reopening decision being made on a local level, the complexion of the new school year can look very different even in districts near each other.

Kylie Schipper, a kindergarten teacher in a small rural district in central Iowa, is preparing to teach her young students in person while prioritizing social distancing. Meanwhile her husband, Leland Schipper, a high school math teacher in a nearby urban district, will be teaching his next semester of courses virtually.

Usually in late summer, the couple shuttles back and forth between each other’s classrooms preparing each space for the first day of school. That ritual looks a lot different this year, with Kylie’s kindergarten classroom undergoing a coronavirus-related overhaul while Leland’s will remain empty as he teaches students online from a home office.

To space out fidgety kindergarteners, Kylie Schipper is eschewing group desks, which would place students in close quarters in little pods of six. Instead, her classroom layout features yoga mats on the floor, spaced 6 feet apart.

“Their little bodies get so bored of sitting, they just can’t do it. And you lose their attention and you lose your focus,” she said. “And so for me, the most important thing was I needed some some way to be able to have them moving, but then be able to have their own space seated and learning from, too.”

She purchased some of the new classroom fixtures herself, and was supported by friends and families as well, who picked ways to help from an Amazon wish list she posted on Facebook.

Her husband has been on his hands in knees in the classroom slicing out kid-size rectangles from a long foam roll, which the couple position at intervals on the classroom floor next to plastic containers in which kids can store books and belongings.

Both teachers are enacting their specific district’s directives. Divergent as the requirements may be, the couple feel they reflect a democratic consensus.

“Part of that is just the communities that they represent, the polling that both of our school districts did of our communities show different results about what people preferred in returning,” Leland Schipper said.

For many teachers, it’s not possible to quit

Back in Montana, Fortner is feeling boxed in, desperately trying to figure out how to balance his commitment to his family with his lifelong vocation. His school system offered options for teachers to take a leave of absence if they weren’t comfortable with teaching in person, but financially he felt that route was a nonstarter.

The father of two, in his mid-40s, is married to a teacher, and they are paying down hundreds of thousands of dollars in mortgage and student debt.

“If my hands weren’t tied, I’d walk away,” he said. “What teacher can afford that? We can’t afford to stay home even if we want to.”

He worried how these reopening decisions would affect an already severe national teacher shortage, and he lamented the lack of discussion on hazard pay for teachers.

“I question my loyalty to a system that isn’t concerned with people who are high-risk,” he said. “I’m worried some teachers won’t be able to do it. They’ll turn around and walk away.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

For now, he will keep presiding over his classrooms, instilling as much as he can the values he hopes students can take from great literature.

“We need to question our relationship with our own humanity. Not everything has to be data-driven or charts and graphs when it comes to who might live or die.”