Editor’s Note: Kate Clarke Lemay is a historian with the National Portrait Gallery, where her projects included “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence” (2019). She is the author of “Triumph of the Dead: American WWII Cemeteries, Monuments and Diplomacy in France” and was the founding coordinating curator for the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative. The views expressed here are hers. Read more opinion on CNN.

Today, women are fighting in combat and earning the title of Green Beret alongside men. It is not uncommon to see a woman soldier cited for valor in the military or otherwise recognized as civilians who demonstrated courage by the American government or other organizations. But a century ago, during World War I, women mostly were limited from the theatre of war, even as medical professionals.

Suffragists, however, seized on the war as an opportunity to bolster their cause, and in 1918, organized the Women’s Oversea Hospitals Unit to serve in France. They were responding to the powerful antisuffragist argument that declared that women should not have the right to vote because they could not prove themselves as full citizens – by fighting for their country.

Yet who knows their story? It may surprise many to find out that more than 100 American women during World War I were decorated by foreign governments – yet none were recognized by the United States, even when they were operating within American-sponsored volunteer groups. Why is it that we are still contending with women being left out of American history, especially military history? Historians must remove women’s history from the margins and place it prominently as American history.

As in 2020, the year 1918, was shaped both by global pandemic and protest. As Americans today process a momentous anniversary – the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment recognizing women’s right to vote – against the current backdrop of Covid-19’s devastating effects, the story of the suffragist doctors is a timely reminder of the honor and respect still due to too many forgotten American women.

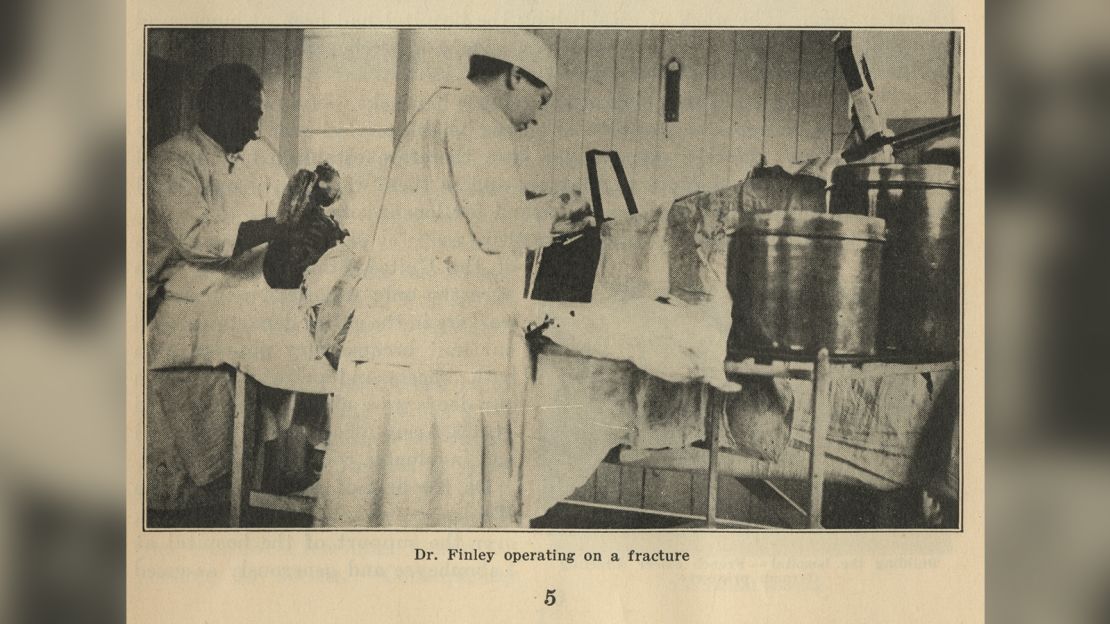

Carrie Chapman Catt, the leader of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), sent the first group of the 78 American women physicians and nurses to France in February 1918. These women, working under the auspices of the newly formed Women’s Oversea Hospitals Unit, were led by Dr. Caroline Sandford Finley. A graduate of Cornell Medical College, Finley was in the top 10 of her class and had worked her way up to lead the department of obstetrics at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Despite having no military training, the suffragist physicians and nurses felt that if they proved themselves in war, it would be impossible to deny women full voting rights back home.

At the end of 1917, suffragists had achieved a few major victories – but not enough. On November 6, 1917, the state of New York passed and signed women’s right to vote in the presidential elections by a surplus of over one hundred thousand “yays.” Other states, including North Dakota, Nebraska, Ohio, Indiana, and Rhode Island each also had secured presidential suffrage for women through state action – but dozens still denied women an electoral voice.

At the federal level, NAWSA and the suffragist doctors and nurses knew how important their war work was; suffrage advocates had been pitching universal suffrage for women as part of the war effort, to show US allies that all Americans were fighting for democracy. One month before they left for France, in January 1918, President Woodrow Wilson announced his support for a women’s suffrage amendment as a war measure. It would take until June 1919, after the war had ended, for Congress to pass it and send it to the states for ratification. The suffrage doctors’ and nurses’ war service occurred during one of the most pivotal moments of the entire decades-long campaign for votes for women.

Suffragists active in NAWSA were almost exclusively white. Black women, although shut out of NAWSA and almost every other organization except for the YWCA and the Red Cross, organized among themselves in order to not be left behind. Rarely were women of color allowed to be sent overseas to offer medical services. Nevertheless, the Red Cross commissioned Dr. Mary L. Brown (1876-1927), a Howard University Medical School graduate, in the spring of 1918. Another Black woman, Dr. Harriet Rice (1866-1958), served with the Service de Santé, the French Medical Corps. Suffragists of all races saw the war as an opportunity to prove their deeply rooted social responsibility as Americans, in ways that could not be ignored.

To fund the Women’s Oversea Hospitals Unit, powerful allies like Katrina Ely Tiffany helped to raise $200,000 for the effort – just under $3 million by 2020 standards. By the spring of 1918, The New York Tribune was reporting French authorities asked the Women’s Oversea Hospitals Unit to set up a hospital specializing in treating gas victims from the front lines in the eastern and northern parts of France. Suffragist doctors, led by Dr. Nellie Barsness (of Saint Paul, Minnesota) and Dr. Irene May Morse (of Clinton, Connecticut), soon found themselves in northern France, specifically in Cempuis, Reims and Nancy, operating gas recovery units – among the first chemical warfare triage stations ever used. The importance of their work cannot be overstated: Between 15,000 and 20,000 men were reported treated in Reims alone.

The suffragists knew that they would be closely watched. No male physicians built their own hospitals during the war, to my knowledge, but the women proved that they could be self-sufficient. The Woman Citizen, NAWSA’s weekly publication, reported that on June 23, 1918, the Women’s Oversea Hospitals Unit opened a hospital for the refugees of war in Labouheyre, located in southwestern France. For this hospital, the American women built 50 barracks from scratch, only accepting assistance in the framing by German prisoners of war, according to The New York Tribune.

Within a month, Dr. Marie Formad (of Newark, New Jersey) and Dr. Mabel Seagrave (of Seattle, Washington) established 500 beds and were serving 10,000 refugees. Thousands of soldiers came to rely on the American women. Dr. Seagrave wrote to her father about how the soldiers likened the American women doctors to a lucky charm and gave them the nickname, the “million dollars.”

Despite working in hospitals, the suffragists still faced grave dangers of war. Fannie Marion Gregory (of New York, NY), who worked as a nurse in Labouheyre caring for French refugees as well as casualties of the United States Army engineers, described her first experiences under fire: “The night raids were horrible. No words can convey the sickening sensation of hearing the explosion of a bomb. The firing of the defense is nerve-racking but when the horrible bomb comes one’s heart is cold at the thought of what it means.”

The American women physicians and nurses admitted to experiencing shock during traumatic events like bombardment. Their health was also at risk due to the 1918 pandemic: two members of the American unit, Winifred Warder and Eva Emmons, both succumbed to influenza while in Labouheyre. Yet the women were steadfast and forged on, folding themselves into the war effort as best they could, in hopes not only for military victory but also for a suffrage victory in the form of the 19th Amendment.

During World War I, the US Army never sanctioned the enlistment of women, although the US Navy did (approximately 11,000 joined in 1917, but only 11 served overseas) as well as the Marine Corps in 1918. Finley and her group served with the Service de Santé, and Finley, the most senior, was promoted to the equivalent of a French Army Captain. Newspaper reports and correspondence indicate the other physicians and nurses were to be paid the equivalent of a second lieutenant’s salary – approximately $100 a month; and the artisan members were to receive a monthly salary of between $30 and $50.

Serving in France not only made it clear that women deserve the right to vote, but it also provided exceptional opportunities for women in the medical profession. The American suffragist doctors and nurses gained invaluable experience, and they went on to become pioneers in their medical fields. For example, Dr. Morse became the first woman professor employed by the University of Wyoming in 1922 – just before she died from the consequences of the gas exposure she suffered during the war while tending to gassed soldiers.

For their heroism under fire, the American women physicians were recognized by French and British governments, but never by an American organization or by the United States. Dr. Barsness, who continued as director of a gas unit in Nancy after the war, was exposed to hazardous gas and earned one of the highest military recognitions of the French government during World War I, the Légion d’honneur du sous-officier.

Dr. Finley was one of three suffragist doctors given the most esteemed French military medal of valor, the Croix de Guerre, whose citation as quoted in the New York Tribune described her as “distinguished, with all her staff, for her courage and her scorn of danger during a bombardment of the hospital by enemy aviators.” Dr. Seagrave was awarded the Médaille des Services Militaires Volontaires Argent from the French government for her outstanding services in treating patients with influenza. And the Prince of Wales awarded Dr. Finley an MBE on the HMS Renown in recognition of her care in Metz of former British soldiers released from German prison camps suffering from influenza.

American suffragists are only one case study of how women civilians who experienced World War I combat circumstances have been left unrecognized (as opposed to male citizens) exemplifying, as the suffragists pointed out, unequal treatment. Moreover, American professional associations at the time were practically silent; only in one instance, in tiny writing near the end of an issue, did the Journal of the American Medical Association report in 1918 on the valorous medals that Dr. Finley received, outlining her award being for “excellent surgery performed under heavy barrage in France.”

Almost unbelievably, most of these women doctors and their incredible war services have been lost to history. Not a single female physician or nurse described in this article has ever been recognized for valorous service by the American military – because they were not allowed to be part of the military. Yet they have been left out of mainstream history narratives. Practically no information exists about the women doctors and the Women’s Oversea Hospitals Unit outside of the rare mention in an obituary or the self-published pamphlet authored by a NAWSA volunteer.

Get our free weekly newsletter

Yet the wartime accomplishments of the suffragist doctors and nurses leave no question regarding the degree to which their trailblazing actions and experiences merit recognition in American history. If women are not treated equally in the historical account, then we have little hope for equality in the present or in the future.