Cai Xia is no stranger to defying expectations. During her years at the Chinese Communist Party’s top training center and think tank, the outspoken professor had surprised many with her liberal ideas and support for democratic reform.

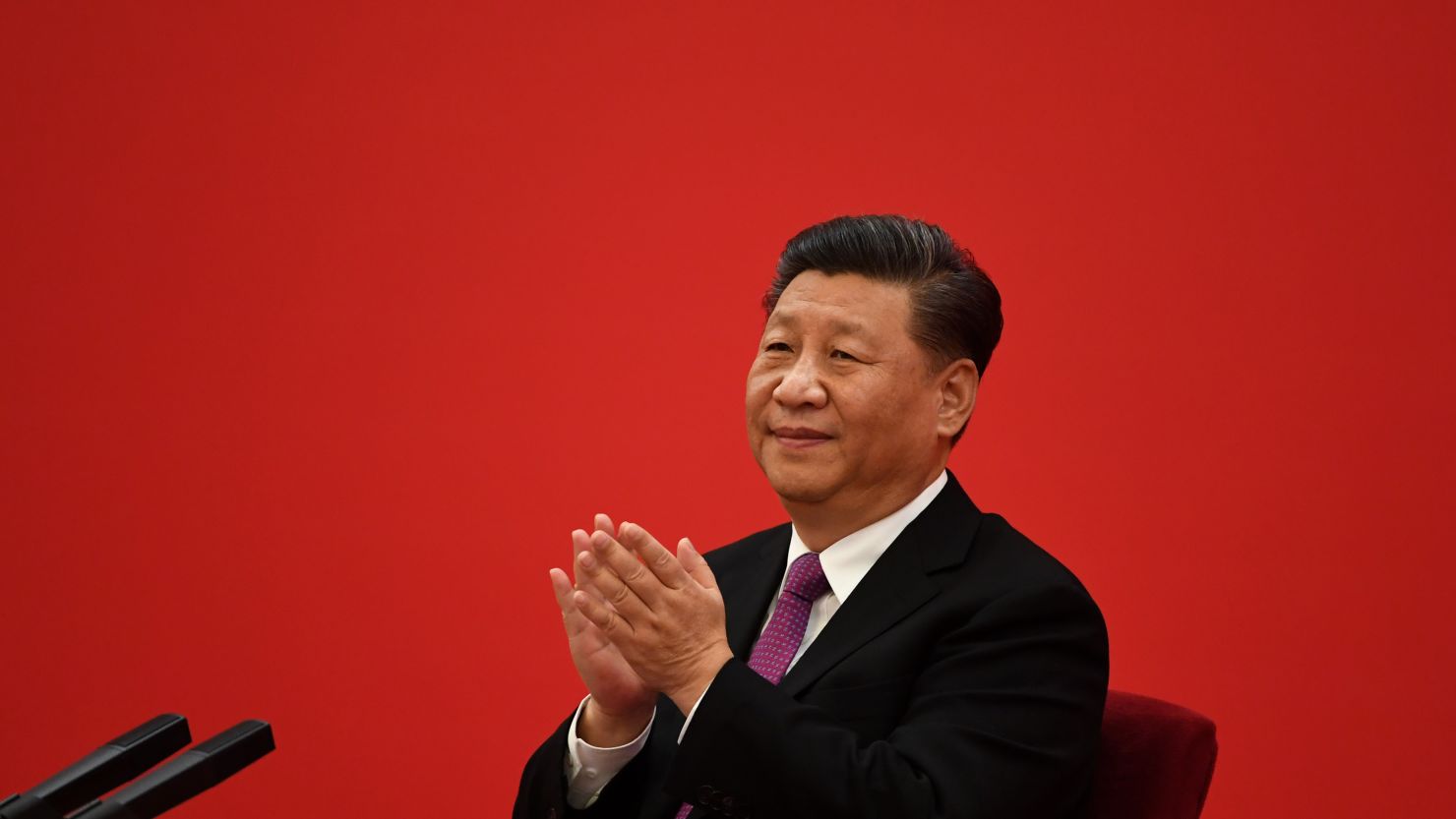

More recently, she caused a stir with a spate of scathing denunciations of China’s ruling elite and the country’s leader Xi Jinping – a rare rebuke from a longtime insider that led to her expulsion from the Party earlier this week.

In an interview with CNN from the United States, where she has lived since last year, Cai went a step further by calling on the US government to double down on its hardline approach towards Beijing. She said she supported the Trump administration’s ban on telecommunications giant Huawei, which Washington claims is a national security risk due to its alleged connection to the Chinese government – an allegation Huawei has repeatedly denied.

Cai also called for sanctions on top Chinese officials and appealed to the international community to join hands in stopping the Communist Party from “infiltrating” global institutions and spreading Xi’s “totalitarian” ideals.

“The relationship between China and the United States is not a conflict between the two peoples, but a contest and confrontation between two systems and two ideologies,” Cai told CNN.

Cai said she had been stranded by the coronavirus pandemic after arriving in the US last year as a tourist. She declined to disclose more details about her current situation or plans for the future, citing fears over her personal safety.

Since coming to power in late 2012, Xi has consolidated his position and authority over the Party, which ranks among the world’s largest political organizations with 90 million members. He has unleashed a sweeping crackdown on political dissent, civil society and the mostly Muslim Uyghur minority in the Xinjiang region, and tightened control over Hong Kong, a former British colony that was promised a high degree of autonomy when it was returned to Chinese rule in 1997.

Now, according to Cai, the Communist Party aims “to replace the free and democratic system of modern mankind represented by the United States, and the values and order of peace, democracy, freedom and justice,” with its own model of governance.

Cai’s comments come as relations between the US and China deteriorate to their lowest point in decades. The world’s two largest economies have sparred in nearly every aspect of their bilateral relationship, including on trade, technology, human rights, and financial flows.

The Trump administration has moved to decouple the two economies, including most recently issuing executive orders that would ban popular Chinese mobile apps from operating in the US. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has portrayed China as an existential threat to the US, giving a speech in July that called for “the free world to triumph over this new tyranny … the old paradigm of blind engagement with China simply won’t get it done. We must not continue it.”

The Chinese government has repeatedly rejected similar accusations. “We have no intention of becoming another United States. China does not export ideology, and never interferes in other countries’ internal affairs,” Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said earlier this month.

Criticism from overseas is of course easier to deflect than criticism at home. Cai, 67, is one of a small but growing number of prominent insider voices who have spoken out against the Party and its authoritarian turn under Xi. But her decades-long career as a Communist Party scholar and adviser has given her criticism a special weight – and dealt an embarrassing blow to the Party.

On Wednesday, the Global Times, a Chinese government-run tabloid, called Cai’s recent public remarks a “blatant betrayal” to China that is “totally indefensible,” and accused her of colluding “with external forces to hurt the interests of the motherland.”?

The Central Party School, where Cai taught for 14 years before retiring in 2012, announced on Monday that she had been expelled from the Party for “making remarks that have serious political problems and damaged the country’s reputation.” It also cut off her pension and other retirement benefits.

The announcement offered scant details, but Cai said the school’s internal statement listed three things that led to her removal: a short essay she wrote in May that decried Beijing’s national security law on Hong Kong as “brutalizing the Hong Kong people,” a leaked audio recording in which she labeled the Party a “political zombie” and referred to Xi as acting like a “mafia boss,” and an online petition she signed in February calling for freedom of speech following the death of Li Wenliang, the Wuhan doctor who was reprimanded by police for attempting to raise the alarm about the country’s coronavirus outbreak. Li later died after catching the virus.

Cai said she shared the essay and speech with friends in private and had not expected her words to make waves online. Both were swiftly censored in China but circulated widely overseas. But now that she no longer belongs to the Party, she said she felt obliged to speak out publicly.

An insider-turned critic

For more than three decades, Cai had closely dissected the Party from within. Throughout her academic career, she examined its internal workings and ideologies. She taught class after class of officials, first at a local Party school in her home province of Jiangsu and later at the Central Party School in Beijing – the elite training ground for China’s most senior cadres and political rising stars.

Her research focus later shifted from ideology to democratic political transition, in the hope that the Party could one day begin to reform itself internally by allowing wider intra-party democracy.

But it was from the inside that Cai watched the Communist Party, which is the sole governing party within mainland China, taking a harder stance on internal debates and dissent. Under former President Hu Jintao, Xi’s predecessor, dissent was still tolerated – although the space was already shrinking, Cai said. Since Xi came to power, however, intra-party democracy has become nothing but an empty name, she added.

“What he emphasized was the concentration of power and the absolute conformity and loyalty to the Party’s central leadership,” she said. “He does not allow dissenting voices from within the Party, punishing those who air a different opinion with Party discipline and corruption charges.”

Last month, the Party expelled Ren Zhiqiang, an influential real estate tycoon and longtime Party member, for “serious violation” of Party discipline and law, after he penned an essay criticizing Xi’s response to the coronavirus epidemic.

In a statement, the Party’s disciplinary watchdog accused Ren of not toeing the Party line on “major matters of principle,” “smearing the Party and country’s image,” and being “disloyal and dishonest with the Party.” It also accused Ren of corruption and handed him to prosecutors for criminal investigation.

Cai had previously voiced support for Ren when the outspoken tycoon was silenced from Chinese social media in 2016 after he questioned Xi’s order that all state-run media must stay loyal to the Party in comments online. This time, she penned an essay in his defense, calling Ren the latest victim of Xi’s “ruthless crackdown” on dissent within the Party.

Speaking to CNN, Cai said Xi’s “reign of terror” did not come from a position of strength – instead, it exposed his deep sense of insecurity. “He’s the one who’s the most scared. That’s why he launched round after round of purges inside the Party,” she said. “The person holding supreme power always feels that others are plotting a power grab.”

In the current political climate, few dare to speak up publicly, Cai said. “When reporting information to their superiors, officials often conceal the truth and only report what they would like to hear. The information conveyed upwards is false, and there is no more scientific, democratic, open and transparent decision making,” she said. “Under such circumstances, major problems will definitely arise in policy making.”

Some critics have blamed China’s slow initial response to the coronavirus outbreak on its political system and culture of discouraging lower-level officials from reporting unpleasant truths.

In the early days of the outbreak in Wuhan, where the virus first emerged, healthcare workers like Doctor Li Wenliang were punished for trying to sound the alarm. Wuhan officials later admitted they had not disclosed information on the coronavirus “in a timely fashion.”

But the Chinese government eventually managed to contain the outbreak, after imposing stringent lockdown measures that brought much of the country to a halt. As the virus spread to other parts of the world, however, many governments, including the United States, have floundered in their own attempts to curb its spread. As of Sunday, the coronavirus has infected more than 23 million people and claimed over 800,000 lives worldwide, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Cai accused the Chinese government of initially covering up the outbreak and causing the virus to wreak havoc across the globe – a claim which Chinese officials have repeatedly and strenuously denied. Propelled by this view and the US-China trade war, Cai said countries are no longer willing to appease China, as they now have a “clear picture of Xi.”

‘Returned to the side of the people’

Cai was born into a so-called “red family” – her grandfather joined the Party in the early years of its founding and her parents fought in the Communist revolution that brought the Party to power. She had a strict upbringing, ingrained with her parents’ revolutionary belief that the people should be freed and empowered to rule the country.

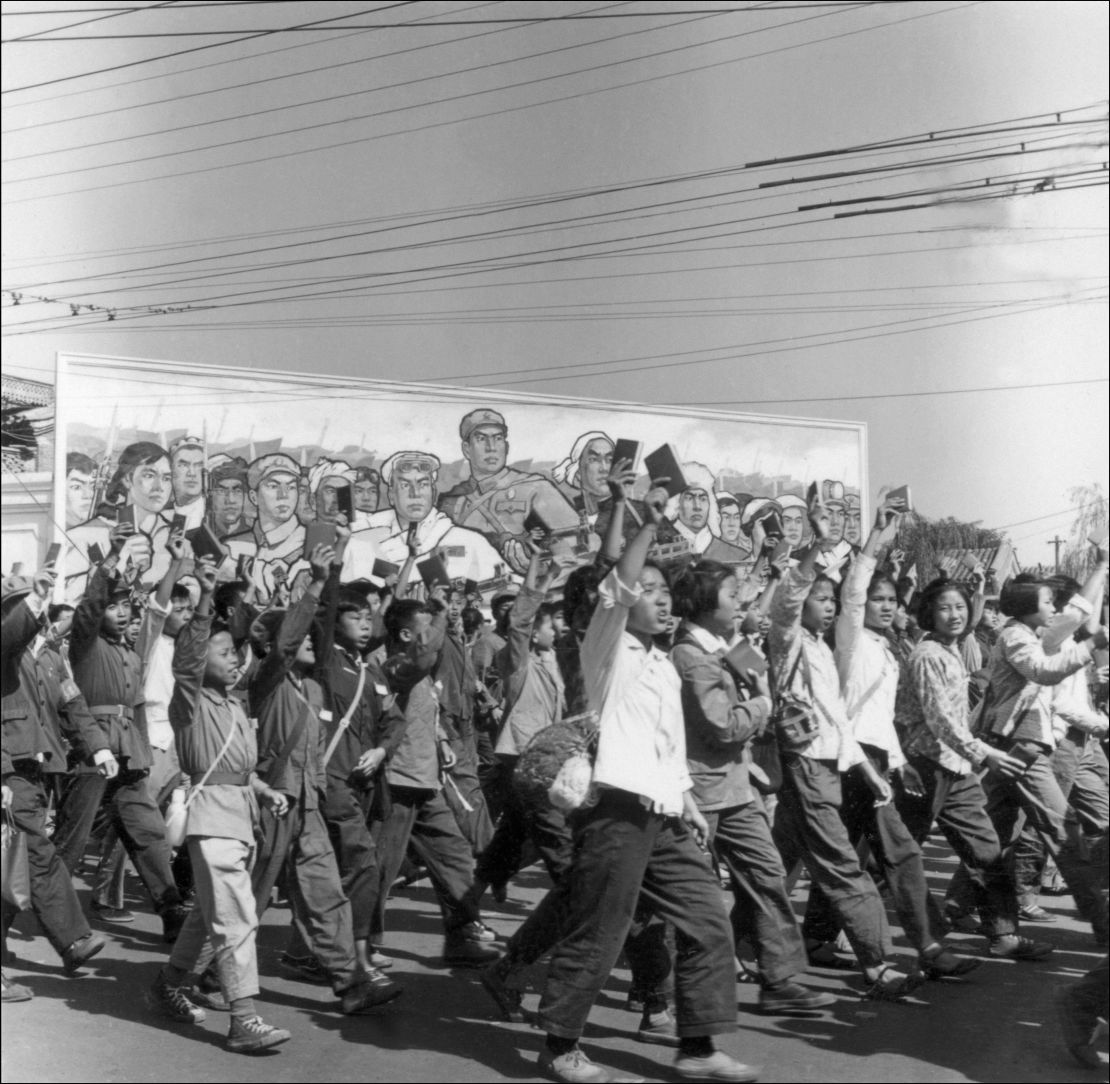

When Cai was a young teenager, Chairman Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution, unleashing ten years of political and social turmoil. In 1966, Cai traveled to Beijing and joined thousands of student paramilitaries, known as the Red Guards, who gathered fervently in a rally in Tiananmen Square to greet Mao. But she said she also witnessed the terror of the movement, including the brutal beatings of teachers.

“I saw how miserable people could be without any rule of law, any protection of rights. It scarred me deeply, and since then I’ve always been on alert that our country cannot return to that era,” she said.

“Since Xi came to power, however, his language, ideas and actions are all harking back to the Cultural Revolution – for us who have been through that period, we’re very sensitive (to that shift).”

Cai said she believes there is widespread discontent within the Party over Xi’s policy directions, especially among the generation of officials who went to college after the Cultural Revolution, rose through the Party ranks during former leader Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening era in the 1980s, and witnessed China’s rapid economic and social development in the ensuing decades. But she said there is little chance for any form of opposition to organize under Xi’s heavy-handed rule.

Cai holds a grim view for the future. Xi is leading the country away from the path of reform and opening, she said. Without internal reforms, conflicts and tensions will build up and one day erupt all at once, causing the sudden collapse of the Party-state system and plunging the country into chaos, according to Cai.

Xi, for his part, has repeatedly said he is committed to reforming China. “What should be and can be reformed, we will resolutely reform. What should not or cannot be reformed, we will resolutely not reform,” he said in a speech commemorating the 40th anniversary of Deng’s policy of reform and opening in 2018.

But according to Cai, the only way to prevent future calamity, is to replace Xi as the top leader, who she accused of “kidnapping” the country.

“China won’t be able to head towards democratic politics under Xi,” she said. “Only by letting Xi step down, can the pro-reform voices arise within the Party and pro-reform forces play their role in adjusting the direction that China is heading in.”

But that might not happen anytime soon. Xi was expected to step down in 2023, but in 2018, he abolished the presidential term limit, clearing the way for him to stay in power indefinitely.

For now, Cai said she was happy to be expelled from the Party, which she said no longer resembled the Party she grew up believing in.

She had already wanted to quit in 2016, when Ren, the property tycoon and fellow Party member, was silenced on social media. Cai spoke out in Ren’s defense, only to be warned herself by the Party to hush up. She argued that she had the right to speak up as a citizen.

“They told me: ‘you’re first a Communist Party member, and your identity as a citizen comes later.’” Cai recalled. “I thought to myself then, I would rather have my rights as a citizen than Party membership.”

“Now, I feel like I’ve finally returned to the side of the people,” she said.