Eight months ago, Meng Hu quit her job as a flight attendant in Guangzhou, China to pursue her dream of becoming an online star.

She gave notice to the airline just before Covid-19 slammed aviation, created a makeshift home studio in her one-bedroom apartment, and started filming herself talking — a lot.

Hu, 27, is an influencer, with a twist. Since January, she’s been working full-time as a live-streaming host on Taobao, Alibaba’s (BABA) eBay-like online marketplace. There, she has built up a following of more than 400,000 fans.

“I’ve been talking nonstop,” Hu said, laughing. “My throat gets really hoarse. [In this job,] you need to talk a lot, because your mood is contagious. You can’t just do things halfway. Only when you talk enthusiastically can you get your audience excited.”

Hu is part of a rising class of creators in China who are racing to get in on live-stream shopping, an emerging form of retail that has grown into an industry worth an estimated $66 billion. Although the trend has been part of Chinese internet culture for years, analysts say the coronavirus pandemic has made it mainstream.

Even the Chinese government has voiced its support, calling the industry the “new engine” of e-commerce growth and encouraging live-streaming as a solution to unemployment, which has risen sharply in China due to the pandemic.

Live-stream shopping is a blend of entertainment and e-commerce. Viewers buy goods online from people who show off their latest finds — from lipsticks to laundry detergent — in real-time videos. Many liken the concept to TV shopping channel QVC, but the Chinese model is distinctly more modern, mobile and interactive. Hosts can give their fans discount coupons and flash deals in real time, while viewers can click to send their favorite stars virtual “gifts.”

But as Hu and other newcomers are discovering, making it in this field is not easy. The industry is tough, and few workers can parlay their skills into a successful career.

The Covid-19 boom

In the first half of this year, ?more than 10 million e-commerce live-streaming sessions were hosted online, according to the government.

As of March, there were 560 million people watching shopping live-streams in China, an increase of 126 million compared to last June, according to a report published by the China Internet Network Information Center. Almost half of them used live-streaming for online shopping, according to the report.

Sandy Shen, a research director of digital commerce at Gartner, said live-stream shopping would have taken two or three years to become a mainstream trend in China prior to the pandemic. Instead, it took two or three months, she said.

Experts project the industry still has a lot of room to grow. In 2019, China’s live-stream shopping market was worth 451.3 billion yuan ($66 billion), according to iResearch, a Shanghai-based market research firm. That could more than double to almost 1.2 trillion yuan (roughly $170 billion) this year, the firm forecast in July.

Analysts predict the trend could catch on overseas, too. In parts of Southeast Asia, for example, Alibaba (BABA)-owned Lazada allows live-streamers to promote merchandise. And Amazon (AMZN) has a home-shopping video-streaming hub for its Western users.

A day in the life

Part of the allure of venturing into this world is the prospect of a big payday. Brands routinely announce tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in sales in a single sitting. Top influencers can earn millions of dollars a year, according to Taobao, which compiles a ranking of the highest paying hosts and their estimated earnings. And even prominent business leaders are getting in on the act.

But experts note that there are also scores of people at home wringing their hands.

“If you are just a normal, ordinary merchant selling on Taobao, and you are just using all your own employees, with no pre-marketing, you’re probably just going to have a couple of hundred people watching. And they will maybe just stop for five or 10 seconds, and if they find it’s not interesting, they’ll just leave,” said Shen.

For people like Hu, the live-stream host in Guangzhou, the ongoing boom presents both “a chance and a challenge.”

“Viewers might have doubled, but there’s probably about seven or eight times more new live-streamers now,” she estimated. “So many people like me have joined live-streaming, and are selling products and doing the [same] thing.”

Hu said she now earns in a month what she used to make in a year. But the hours can be grueling. She typically spends seven hours a day speaking on live-stream to her fans, offering deals on everything from vacation getaways to snacks to skincare products. After that, she spends hours each night reading up on products she plans to sell.

“Every day I wake up, I work, work, eat, work, and sleep,” she said. “It is hard.”

The production takes a village. More than 20 people work behind the scenes to support Hu’s work, directly or indirectly, by her estimate. That includes teams from a local talent agency that help her choose which products to feature, what discounts to offer fans and how to plan her filming schedule. Her husband helps out with odd jobs and occasionally pops up on camera, too.

Hu and her team make money, meanwhile, through a couple of avenues: The companies pay for their products to be featured, and then Hu earns a commission off of each sale she makes. A typical commission rate varies from 6% to 16% depending on the platform, according to the iResearch report.

The new gig economy

Like most of the world, China has been rocked by an economic and jobs crisis this year, although the country has recently shown signs of a rebound. To help keep people afloat, the government has seized on the trend by encouraging people to live-stream.

This February, for example, China’s Ministry of Commerce encouraged e-commerce platforms to help farmers sell their produce online, particularly through live-streaming.

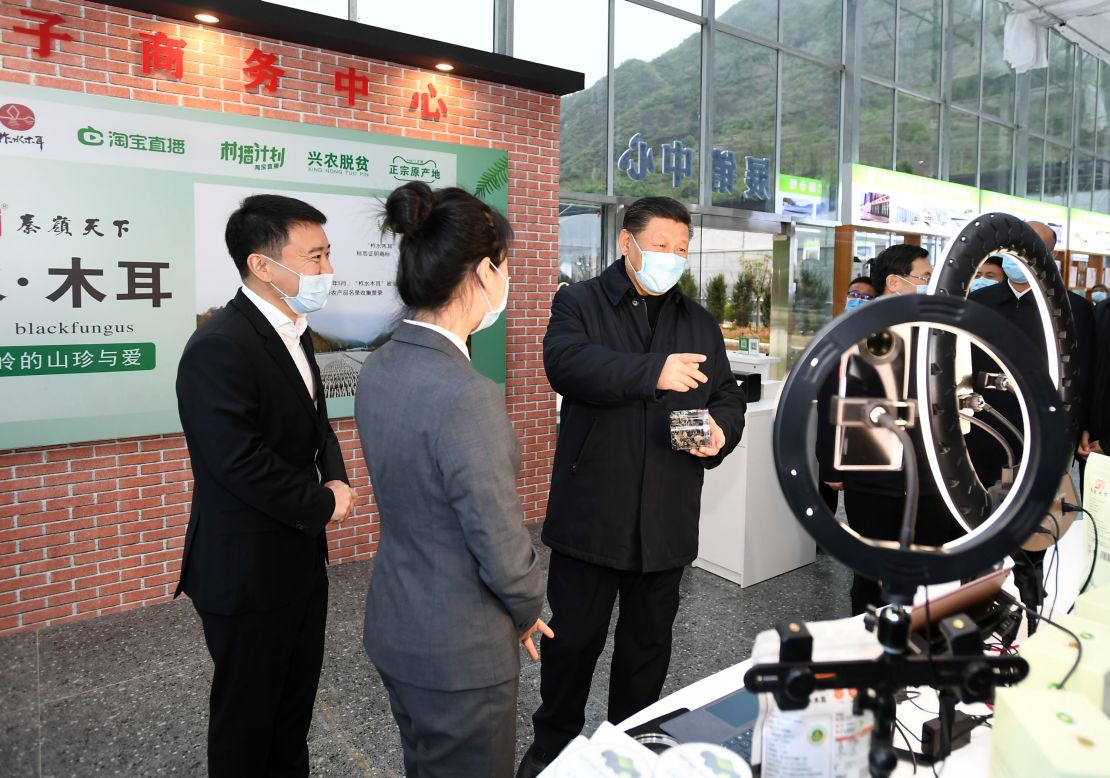

Even Chinese President Xi Jinping has taken notice. In March, he visited a village in northwestern China where he spoke with residents who were selling agricultural goods over live-stream, according to the state-run news agency Xinhua. Xi praised the power of e-commerce, saying it had great potential to help keep people out of poverty.

In May, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security even added “live-streaming host” to its list of recognized professions, meaning the government would start counting those people as officially employed. State media said this would help the country create new “job pools” to balance out the loss of manufacturing jobs that had been wiped out by the pandemic.

Some local governments are even working to transform their towns into live-stream shopping hubs. In Guangzhou, authorities are hoping to turn the city into China’s “live-streaming capital.” To that end, in June they held a three-day live-stream shopping “festival,” where businesses conducted more than 200,000 broadcast sessions, according to state media.

“As the economy recovers, the job market is in fact expanding,” said Fu Linghui, a spokesperson of the National Bureau of Statistics, at a press briefing last month. He singled out “gigs like live-stream shopping” as the kind that were “vital” to stabilizing the market.

“For the government, they see this as a trend that can help keep the economic growth, and also help keep the employment,” said Shen. “They view this as an opportunity, and it is. I think if you create the infrastructure, give support, it can definitely help lift the economy.”

The hard truth

Even so, the industry’s impact on the economy is probably limited, according to Xiaofeng Wang, a senior analyst at research firm Forrester. She noted that live-stream shopping is still a very small percentage — estimates suggest around 5% — of the country’s e-commerce market, and a tiny share of the overall retail sector.

“I don’t think live-stream e-commerce alone will save the economy,” Wang said.

Of the 400,000 people that China’s Commerce Ministry says hosted a live-stream shopping event in the first half of 2020, it’s likely that only 5% to 10% will succeed and earn a living, estimated Iris Pang, chief economist of Greater China at ING.

She said it was hard to predict how many jobs had been added to China’s economy so far because many people working in this field were not full time.

“I think it will boost job numbers only by a little,” Pang said. “It shouldn’t be big enough to move the needle.”

“People who want to do this should be expected to work really hard,” said Heng Xia, CEO of NStar MCN, a Hangzhou-based talent agency. Nice represents Hu and more than 150 other online personalities.

“This is a high intensity job,” Xia said. “Most people can’t really do it. We’ve hired many new graduates, and some of them couldn’t make it.”

That’s the question currently facing Seven Zhou, a live-streamer in Hebei province who’s trying to carve out a new career on the short video app Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok. In January, the former consultant was put on furlough after his company lost clients due to fallout from the pandemic. Like Hu, he decided to quit with high hopes of making it big.

But as time went on, Zhou said, he realized that goal was more unattainable than it looked. Douyin requires anyone hoping to become a seller on its platform to have at least 1,000 followers, but he found it tough to reach that milestone. To find an audience, he started hosting two-hour live-stream “chats” each day. The experience was painfully “awkward,” he said.

Few viewers stopped by his channel. His videos flopped, hardly getting any “likes.”

Eight months on, Zhou is wondering whether he is cut out for this business. The 30-year-old hasn’t yet decided whether he’ll throw in the towel, but says he is disillusioned with the industry and all the stories of overnight success.

“It hasn’t gone well,” he said. “The system isn’t as simple as it seems.”