Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito on Monday used the case of a Kentucky clerk who refused to give gay couples marriage licenses to declare that religious liberty has been under siege since the Supreme Court in 2015 found a constitutional right to same-sex marriage.

In some respects, the objections of conservatives Thomas and Alito simply echoed their dissents five years ago in Obergefell v. Hodges. But timing is everything, and nothing is quite the same at the Supreme Court since the September 18 death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The court is on the cusp of a more potent conservative majority with possible appointee Amy Coney Barrett.

It is not as easy to declare – as it was just a month ago – that the high court is unlikely to reverse the milestone decision that now seems woven into American life. Nearly 300,000 same-sex couples have married since the decision, according to a May report by the Williams Institute at UCLA.

With the passing of Ginsburg, and the 2018 retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, only three of the justices from that 5-4 majority are still on the bench: Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

While many court commentators have focused on the future of the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that made abortion legal nationwide, Thomas’ statement, joined by Alito, offered a reminder that other precedent that inspires religious objections may also hang in the balance.

Obergefell, Thomas wrote, threatens “the religious liberty of the many Americans who believe that marriage is a sacred institution between one man and one woman.”

Gay rights advocates and Democratic leaders immediately attacked the justices for abandoning judicial restraint and threatening the future of same-sex marriage. And some members of the Senate Judiciary Committee, set to take up Barrett’s nomination next week, may now be more inclined to put more attention on the nominee’s views related to LGBTQ rights.

Referring to the Senate GOP fast-tracking of the Barrett confirmation process, Sen. Minority Leader Chuck Schumer declared Monday in a Facebook post: “Make no mistake: This is what’s at stake with Republicans trying to force through this illegitimate process. People’s rights. Ending marriage equality. Stripping away LGBTQ+ rights. We are fighting to stop it.”

Barrett, currently a US appeals court judge based in Indiana, has a record of deep conservatism. She has also been vocal about her devout Catholicism, a subject of concern for some of her Democratic critics.

Joining Thomas and Alito in dissent from the 2015 Obergefell decision were Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in 2016.

Barrett, a former law clerk to Scalia, said in the Rose Garden when President Donald Trump unveiled her nomination on September 26, “His judicial philosophy is mine too.”

Roberts has a mixed record on gay rights. The chief justice felt so strongly that the justices in the Obergefell majority had taken a wrong turn – involved themselves in a matter best left to legislators – that he read portions of his dissenting statement from the bench five years ago. It was Roberts first and only dissent from the bench – a dramatic step taken when justices want to call public attention to their positions.

In June, however, Roberts signed onto the majority’s decision expanding civil rights protection for gay and transgender workers under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

‘Court’s cavalier treatment of religion’

In their statement Monday, Thomas and Alito focused on the consequences of the ruling for religious believers, including clerk Kim Davis, a Christian who had refused to issue marriage licenses in 2015 based on her religious objections to same-sex unions. Her case made headlines as she was held in contempt of court and briefly jailed.

Thomas and Alito agreed with the Supreme Court majority that her appeal should not be heard. But they noted that the dissenting justices in Obergefell had predicted “assaults on the character of fairminded people” who have religious objections. Davis, they said, was a leading example.

“When she chose to follow her faith, and without any statutory protection of her religious beliefs, she was sued almost immediately for violating the constitutional rights of same-sex couples,” Thomas wrote. “Davis may have been one of the first victims of this Court’s cavalier treatment of religion in its Obergefell decision, but she will not be the last.”

Thomas asserted: “Due to Obergefell, those with sincerely held religious beliefs concerning marriage will find it increasingly difficult to participate in society without running afoul of Obergefell and its effect on other antidiscrimination laws.” He insisted the 2015 case “enables courts and governments to brand religious adherents who believe that marriage is between one man and one woman as bigots, making their religious liberty concerns that much easier to dismiss.”

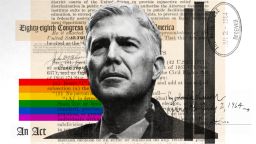

Neither Roberts nor fellow conservatives Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh joined Thomas’ statement. The same-sex marriage views of the latter two, appointed by Trump in 2017 and 2018, respectively, are not known.

More than any of the current justices, Thomas has called for re-examination and reversal of precedents. Most notably, he has attacked the constitutional underpinnings of Roe v. Wade. None of the justices publicly dissented from taking up Davis’ case. Thomas wrote that her petition “implicates important questions about the scope of our decision in Obergefell, but it does not cleanly present them.”

James Esseks, director of the American Civil Liberties Union LGBT & HIV Project, said in a statement: “It is appalling that five years after the historic decision in Obergefell, two justices still consider same-sex couples less worthy of marriage than other couples.”

Esseks noted that the court is scheduled to take up a case one month from now, Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, that centers on publicly funded foster care agencies that do not accept same-sex parents on religious grounds.

“When you do a job on behalf of the government – as an employee or a contractor – there is no license to discriminate or turn people away because they do not meet religious criteria,” Esseks said. “Our government could not function if everyone doing the government’s business got to pick their own rules.”