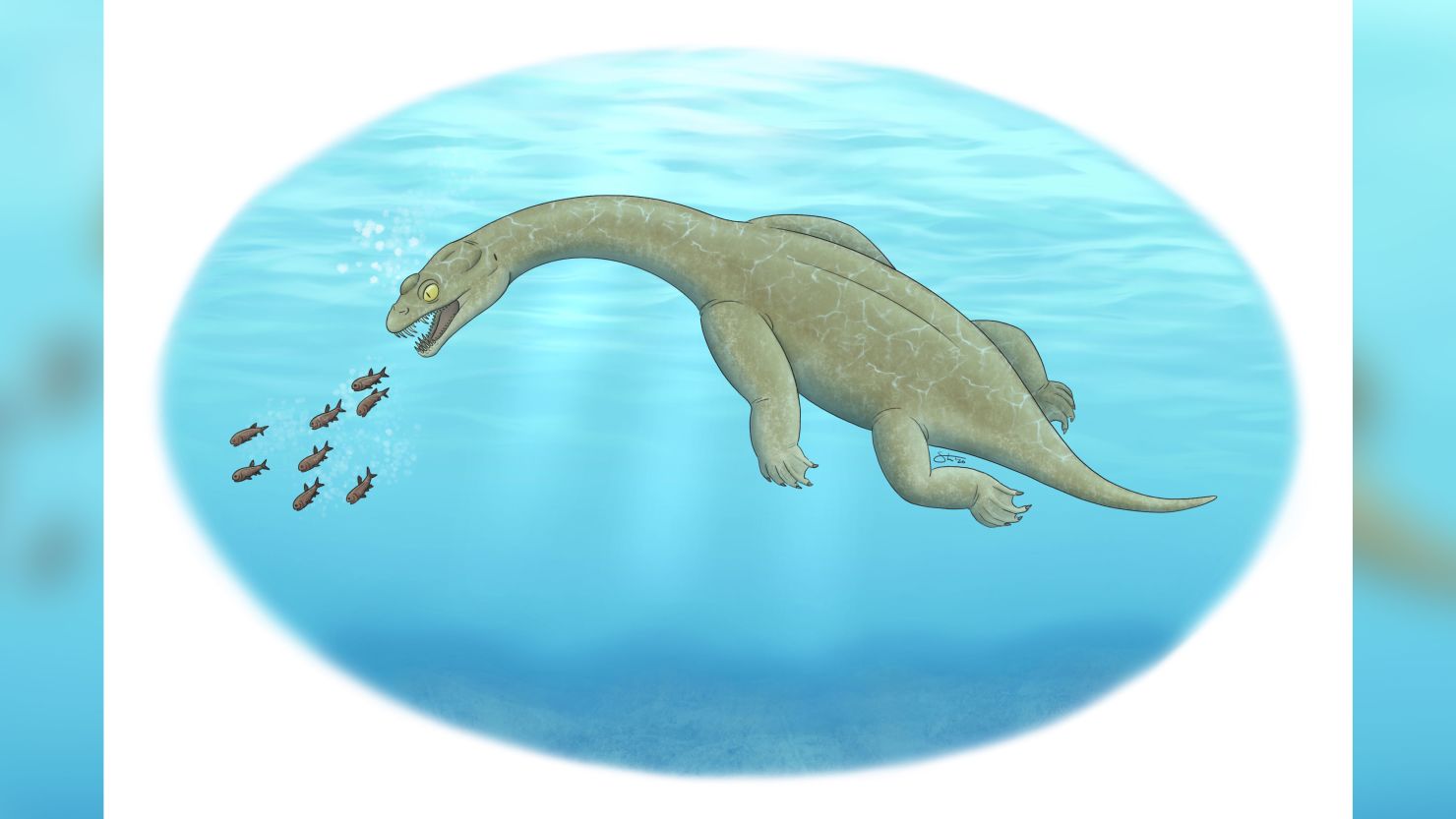

Scientists have discovered a new lizard-like speciesthat lurked in shallow water to pick off its prey – with the help of a short, flat tail used as a float.

Some 240 million years ago, the Triassic predator Brevicaudosaurus jiyangshanensis skulked, nearlymotionless, in the sea – and researchers found clues in its skeleton that could explain its unusual hunting methods.

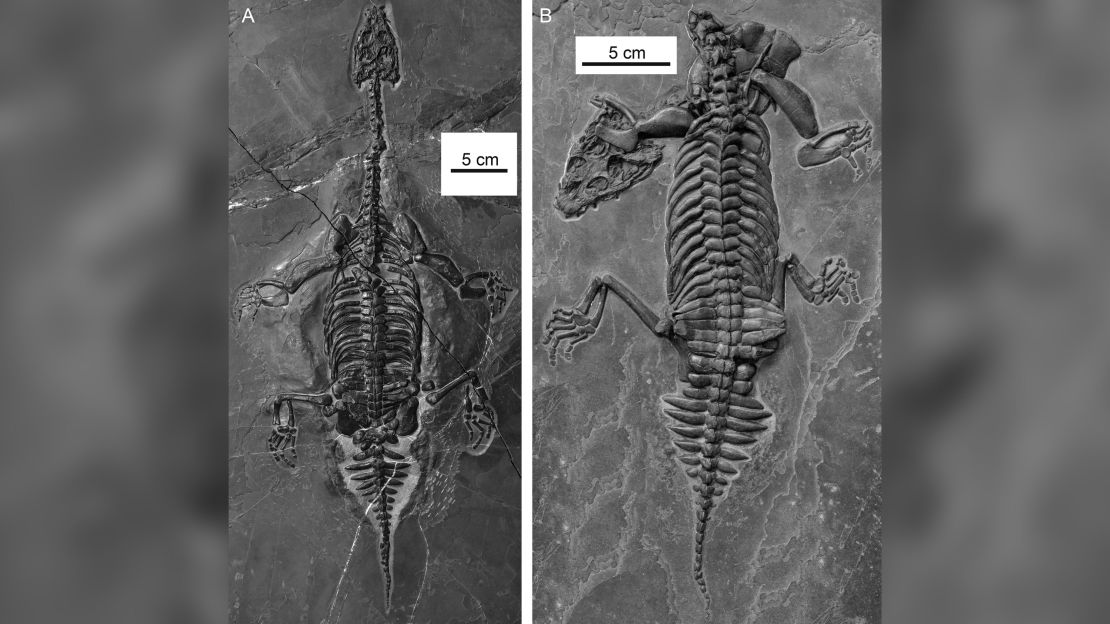

Scientists at the Chinese Academy of Scientists in Beijing and Canadian Museum of Naturein Ottawa studied two skeletons discovered in a thin layer of limestone in two quarries in southwest China. The most complete skeleton, measuring just under 60 centimeters long, was found in a quarry in Jiangshan.

Experts identified the 240 million-year-old remains as a previously unknown species of nothosaurs: small-headed marine reptiles with fangs, flipper-like limbs and a long neck. Usually, nothosaurs had a longer tail, which experts think was used for propulsion – but the newly discovered reptile had a short and flat tail.

The reptile’s forelimbs were more developed than its hind limbs, and could have played a role in helping the animal to swim, the researchers noted. With its thick and dense bones – including vertebrae and ribs – it was likely stocky and stout in appearance.

What’s more,Brevicaudosaurus jiyangshanensis was not necessarily a speedy swimmer, experts believe, based on the evidence. However, its dense bones may have afforded it an advantage: stability. Its thick, high-mass bones could have made it neutrally buoyant in shallow water, and with the help of its flat tail, the predator could float motionless underwater while using little energy.

Stealth hunter

The creature, researchers also believe, could have used its neutral buoyancy to stalk the seabed in search of its next meal.

“Our analysis of two well-preserved skeletons reveals a reptile with a broad, pachyostotic body (denser boned) and a very short, flattened tail,” said study co-author Qing-Hua Shang, a paleontologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in a statement. “A long tail can be used to flick through the water, generating thrust, but the new species we’ve identified was probably better suited to hanging out near the bottom in shallow sea, using its short, flattened tail for balance, like an underwater float, allowing it to preserve energy while searching for prey,” Shang added.

The reptile was well suited for underwater hunting: neutral buoyancy should also have enabled it to walk on the seabed searching for slow-moving prey. Meanwhile, the skeleton’s high density ribs also suggest the reptile had large lungs, increasing the time the species could spend without surfacing.

Paleontologists found another feature that would help Brevicaudosaurus in its underwater exploits: The creature also had thick, long stapes – bar-shaped bones in the middle ear, used for sound transmission – which could have helped the reptile hear under the surface.

“Perhaps this small, slow-swimming marine reptile had to be vigilant for large predators as it floated in the shallows, as well as being a predator itself,” said co-author Xiao-Chun Wu, a paleobiologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature, in a statement.