At the first meeting between Donald Trump and Chinese leader Xi Jinping, held over chocolate cake and sorbet at the US President’s vast Mar-a-Lago private club in Florida, the two leaders seemed on the brink of establishing an unlikely and potentially special relationship.

Trump, less than three months into his first term, had spent his election campaign denouncing the Chinese government for undermining the United States, through a wide trade imbalance and cheap labor. “We can’t continue to allow China to rape our country,” Trump said in May 2016.

But when Trump was standing alongside Xi at Mar-a-Lago the following April, his tone changed dramatically. The two leaders exchanged compliments during a news conference, with Trump describing their relationship as “outstanding.” Pictures from the meeting showed the two men sitting side-by-side, smiling broadly, on a golden couch.

“It was a great honor to have President Xi Jinping and Madame Peng Liyuan of China as our guests … Tremendous goodwill and friendship was formed,” Trump tweeted shortly after the visit.

Three years later, and that “outstanding” relationship is a distant memory.

Trump no longer talks about his friendship with Xi as relations between the two countries continue to plummet, amid stark divisions over trade, technology, human rights and accusations of Chinese expansionism.

As Trump battles for reelection in November’s presidential election, experts now say that Xi may have missed a golden opportunity to establish a more beneficial relationship with the US President.

In Trump, China found an American leader who seemed focused on transactional politics and trade deals, rather than human rights and Chinese foreign policy, both topics which the ruling Communist Party have been traditionally eager to avoid.

It wasn’t just their relationship with the US either. More broadly, Trump’s isolationist “America First” foreign policy offered Xi a clear opening to assert China’s global leadership credentials across a range of key policy areas – from the climate crisis to free trade.

But rather than building up goodwill, China chose to intimidate its global partners and indulge in fierce nationalist rhetoric. And instead of becoming a global power to rival the US, China saw its reputation plunge around the world.

How Trump could have helped Xi

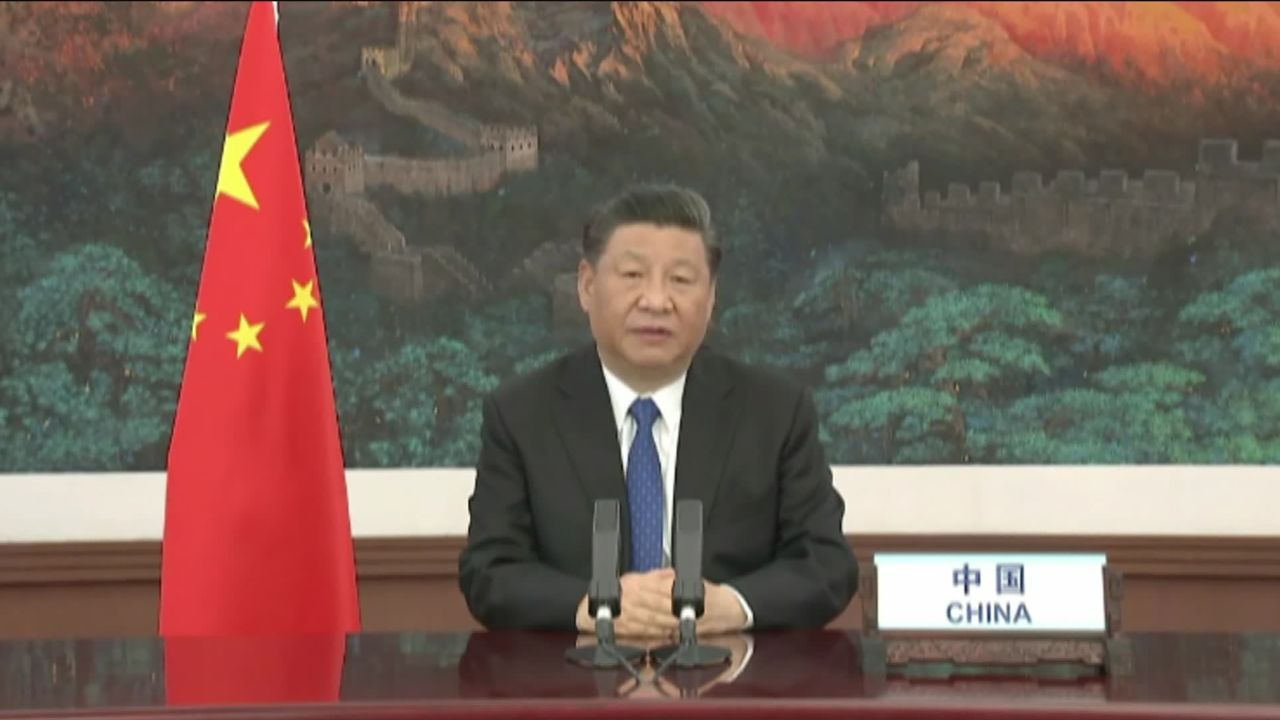

Less than a week before Trump took office in January 2017, Xi took the stage in Davos, Switzerland, at what appeared to be the dawn of a golden era for China and Beijing’s international influence.

In a speech to the global liberal elite at the World Economic Forum, held in the Swiss Alps, Xi called for countries to shun protectionism in a clear swipe at Trump’s “America First” rhetoric.

His speech was well received among economic leaders. In his introduction of Xi at Davos, World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab said “the world is looking to China.”

Daniel Russel, who was US assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs under President Barack Obama, said that it was Trump’s anti-globalist rhetoric as much as Xi’s words that made China look like a potential alternative global leader to the US.

“At the same time that Xi was hypocritically claiming to be the grand defender of the global system, Trump was attacking it viciously and putting forward a very nationalist jingoistic message. So that magnified the contrasts and widened the gap,” said Russel, who is now vice president of international security and diplomacy at the Asia Society Policy Institute.

Across a wide range of areas, Trump’s policies opened an opportunity for China to take a more leading role in global affairs. Leaving the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in January 2017 opened the door for China to push its own regional trade deal. After Trump ditched the Paris cimate change accords five months later, Xi told a gathering of Communist Party leaders China would be a “torch bearer” on the issue.

When Trump began to distance the US from its allies, calling on long-time partners to pay their “fair share” of defense spending, Beijing took the opportunity tomove closer to regional powers.

China and Japan planned an exchange of state visits for the first time in a decade, thawing a deep diplomatic freeze which had been in place since a territorial dispute over islands in the East China Sea in 2012. South Korean leader Moon Jae-in announced in June 2017 that the deployment of a controversial US-made missile defense system, heavily opposed by China, would be deferred. Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, leader of one of the US’s closest allies in Asia, said that he “loved” Xi Jinping.

“I think at the start of the Trump administration, China was being seen by the rest of the world as a country which potentially could provide a good steadying role in steering the world though the next turbulent phase in the coming few years,” said Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute think tank in London.

For Xi, it was a remarkable 12 months. The Chinese government saw its stock rise internationally, built a close relationship with the new US President and had been handed strategic victories on trade, foreign policy and climate change. In short, “the Trump administration was a godsend for the Communist Party of China,” said Tsang.

Why it went wrong

Yet in October 2020, nearly four years after Trump was inaugurated, China’s global reputation is at its lowest point in years.

Poll numbers released by Pew Research on October 6 found that the Chinese government was viewed negatively in all 14 major countries surveyed, including Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan and the US. In 2002, 65% of US citizens surveyed viewed China favorably – in 2020 that number is just 22%. A massive 74% view China unfavorably.

The coronavirus pandemic, first reported in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019, has severely damaged Beijing’s reputation as countries struggle to deal with rising caseloads. Government leaders and officials around the world, including Trump, have accused Beijing of mishandling the outbreak by playing down the severity of the virus in the early stage, and allowing it to spread overseas.

But even before the outbreak, China was finding its reputation was beginning to dim, especially among Western nations.

For years, Australia has been at the forefront of the West’s uneasy embrace of China – a close US ally whose largest trading partner is Beijing. With an unpopular and isolationalist American leader, China had never had a better chance to woo Australia.

But when the Australian government introduced legislation in 2018 against foreign interference, Beijing was furious, seeing the legislation as targeted at them. Leaders in Canberra were cut off from Beijing, visas were frozen, valuable exports to China suddenly faced increased customs checks and an Australian writer was charged with spying.

In 2017, more than 60% of Australians had a positive view of China, according to Pew. By 2020, it was just 15%.

The treatment of Australia wasn’t unique, however. Relations between Canada and the US were strained under Trump, who clashed with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau over immigration and trade. But instead of moving closer to Trudeau, Beijing plunged relations with Ottawa into a deep freeze.

Following the arrest of a top executive and daughter of the founder of the Chinese tech giant Huawei in Canada at the request of the United States in late 2018, two Canadians were detained in China. The two men, entrepreneur Michael Spavor and former diplomat Michael Kovrig, were later charged with spying and handling state secrets. In 2019, China moved to block Canadian canola seed and meat exports, leading to uncertainty among other Canadian businesses operating in China.

On the 50th anniversary of Canada beginning diplomatic ties with China on October 14, Trudeau delivered a stern rebuke of Beijing’s international diplomacy and human rights record.

“We will remain absolutely committed to working with our allies to ensure that China’s approach of coercive diplomacy … is not viewed as a successful tactic by them,” he said.

In neighboring India, the rise of populist Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014 had presented an opportunity for Xi and his government to woo New Delhi, a rising regional power that had long been courted by Washington.

In 2018, it seemed like Xi was making headway. The two sides resolved a heated border dispute peacefully and the Chinese leader met with Modi in Wuhan for a two-day informal summit, where the two strongman leaders were pictured sipping tea and strolling through ornate gardens.

But two years later, India’s relationship with China has nosedived to its lowest point in years. A border dispute between the two nuclear-armed countries in June, where more than 20 Indian soldiers were killed, has pushed New Delhi closer both militarily and diplomatically to Beijing’s rivals, the US and Japan. New Delhi has also banned a raft of popular Chinese-owned apps, including video-sharing giant TikTok, in a major blow to China’s tech sector.

Yinan He, associate professor at Lehigh University’s Department of International Relations, said that, over the past three years, when Beijing wasn’t actively starting diplomatic fights with other countries it often talked down to or intimidated them.

“The behavior of China under Xi Jinping really enraged many other countries,” she said.

Beijing has also faced growing criticism within the international community over several domestic controversies, including its ongoing crackdown on human rights and dissent, the erosion of civil rights in Hong Kong, and military expansionism in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait.

In particular, the treatment of Uyghur Muslims in the western Xinjiang region has become a major concern for countries around the world. On October 6, Germany presented a statement to the United Nations on behalf of 39 countries, mostly from Europe and North America, publicly condemning China’s actions in Xinjiang, where up to 2 million people, mostly Turkic minorities, are believed to have been placed in detention centers.

But in the face of international criticism, the ruling Chinese Communist Party has not relented. In fact, Beijing has moved to embrace a new breed of aggressive diplomacy to combat what it has denounced as unfair and biased attacks on China.

Dubbed “wolf warrior diplomacy” after a series of aggressively patriotic Chinese films in which the hero bests US special agents, this emboldened form of diplomacy encourages officials to forcibly denounce any perceived slight to Beijing and the Communist Party.

In July 2019, Zhao Lijian, then a counselor at the Chinese Embassy in Pakistan, began to hit back against the US government on social media over allegations of human rights abuses in China. Zhao accused the US of criticizing China while ignoring its own domestic problems with racism, income inequality and gun violence. Zhao was later promoted, becoming one of three rotating spokespeople for the Chinese Foreign Ministry.

Though the aggressive behavior has estranged diplomatic partners, Jessica Chen Weiss, associate professor of government at Cornell University, said the real target remains domestic.

According to Weiss, the authoritarian nature of China’s government means that it can’t brook any concession internationally that might seem like weakness at home. To the Communist Party, weakness might spell the end of its time in power.

“When push comes to the shove the Chinese government has to first and foremost focus on regime security,” said Weiss.

Experts say that in recent months there has been discussion within the Chinese government over whether these “wolf warrior” tactics have hurt their country more than they’ve helped. But for now, with international concerns over its handling of the coronavirus growing louder, any chance of a short-term revival for Beijing’s global reputation seems unlikely.

Weiss said that, in fact, China’s system of government may not actually have ever been up to the challenge of becoming the world’s leading superpower, at least not in the model of the US.

The Chinese government places as much importance on being feared as being loved, Weiss said, and that severely limits its ability to wield soft power and form close diplomatic relationships. According to Weiss, China is unlikely to take the US’ place, no matter how much Trump pulled back on the world stage.

“(Beijing wants to ensure) that nobody thinks China can be pushed around, or taken advantage of,” she said. “That emphasis on deterrence and intimidating dissent has conveyed Chinese resolve but it undercuts Beijing’s efforts to showcase its international image as a benign global leader.”

Broken bond

This year, Trump has been eager to inflame popular anger against China for its handling of Covid-19 – at least in part to distract from his administration’s own failure to contain the virus domestically.

He regularly describes the disease as the “China virus” and has placed a large proportion of the blame for the escalating US epidemic at Beijing’s door.

Yet despite his regular attacks on China, Trump never attacks Xi personally.

On August 11, seemingly more in sorrow than anger, Trump said he used to like Xi, but he didn’t “feel the same way now.”

“I had a very, very good relationship, and I haven’t spoken to him in a long time,” he told Fox Sports Radio.

Xi and Trump are now a long way from where they started three and a half years ago, and in that time Beijing’s reputation around the world has suffered.

“Anti-China sentiment is at its highest levels in decades … and Beijing is aware of that,” Weiss said.

As early as August 2018, Chinese officials in private were voicing their concerns that Xi was mishandling the US relationship and risking a disastrous plunge in bilateral relations. Those voices are only likely to grow louder ahead of the 2022 National People’s Congress in China, where Xi would normally be expected to hand over power to a chosen successor.

“I suspect that Xi might be facing some internal challenges from people within the Communist Party who are not happy about his heavy-handed style,” said He, the Lehigh University China expert.

But whether or not China has taken advantage of the Trump administration’s shrunken presence on the world stage, experts said that in the long run, the fundamentals favor Beijing and Xi.

Russel said that the US and other leading nations were heavily reliant on China and the massive wealth generated by its economy, making any moves towards a broader decoupling and a return to a Cold War level of separation unlikely.

“If you look at it from China’s point of view … are you going to call into question the financial goose that lays the golden egg?” he said.