Lewis Hamilton has made history. Now a seven-time Formula One world champion, the Englishman equaled Michael Schumacher’s record with a stunning victory at a wet and tumultuous Turkish Grand Prix on Sunday.

Upon winning the race on Sunday, Hamilton was overcome with emotion and said over the radio through tears, to his engineers but to the wider world too, “That’s for all the kids out there who dream the impossible. You can do it too, man! I believe in you guys.”

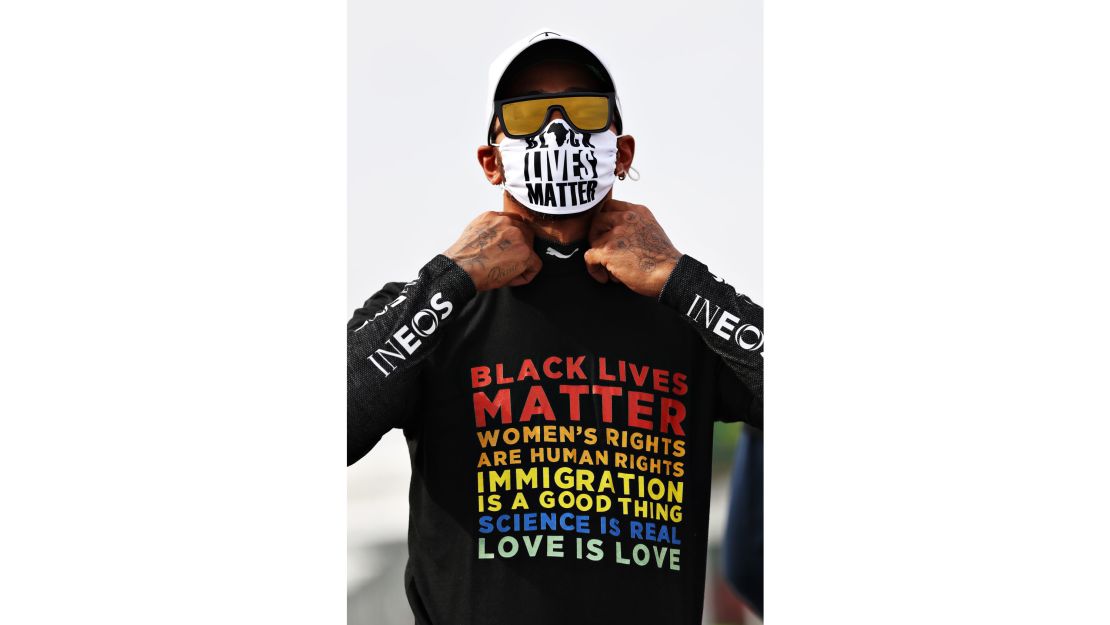

Hamilton’s rise through motorsport is incredible because such a story is so rare. He is F1’s first and only Black world champion in its 70-year history and a racing great from a humble background.

“It is no secret that I have walked this sport alone as the only person of color here,” he told reporters after record-equaling feat on Sunday. “You can create your own path and that is what I have been able to do, and it has been so tough. Tough doesn’t even describe how hard it has been.”

But will there ever be a champion like Hamilton again? Will we ever see another working-class driver or a person of color achieve sustained success in motorsport?

READ: Lewis Hamilton, Formula 1’s voice and conscience

In 2015, Mercedes team principal Toto Wolff estimated that to traverse the many levels of motorsport – from entry level karting, to Formula Renault, onto Formula 3, GP2 and then to F1 – it would cost a driver €8 million ($9.4 million) total.

Five years later, it seems fair to assume that that figure will only have increased.

PA media’s F1 correspondent Phil Duncan believes the sport is fortunate to have had even one champion of the caliber of Hamilton.

“It’s almost incredible that we’ve actually had one [Lewis Hamilton] in the first place, really,” he tells CNN Sport.

“He got there because he was good, but in a way [he is] fortunate that he was picked up by McLaren and Mercedes at 13, who were then effectively able to bankroll his future career.”

Prior to being signed to McLaren by Ron Dennis, Hamilton’s father Anthony famously remortgaged his house three-times and, at times, held four jobs to fund his son’s karting career. But unless a driver’s parents’ house is valued at a few million dollars, that may not be a possible route nowadays.

In 2019, Hamilton lamented the lack of working-class drivers making it to the grid, saying: “There are very few, if [any] working-class families on their way up. It’s all wealthy families.

“I’ve got a friend of mine who was nearly in Formula One and then he got leapfrogged by a wealthy kid and then his opportunity was gone.”

Traveling to races in a caravan

Current Renault driver Esteban Ocon matches Hamilton’s background, albeit from across the English Channel.

The 24-year old’s parents sold their house to fund Ocon’s karting passion, he revealed to Reuters in 2017. The family lived and traveled to races in a caravan that, when not at race weekends, they would park in front of Ocon’s school.

He didn’t mind the lifestyle, saying, “I was 11 or 12 or something. I was happy to live in the caravan back then. I was enjoying my life, I was doing karting all the time and it was awesome for me.”

But, like Hamilton, without the immense sacrifice of his parents, he would not have been able to continue in karting.

The same goes for Hamilton’s fellow seven-time world champion Schumacher.

Schumacher’s bricklayer father Rolf reportedly built his son’s first kart from scrap. To continue funding Michael’s karting career, Rolf took a second job working as a mechanic on other people’s karts, before the future champion was discovered by sponsors.

Four-time world champion Sebastian Vettel has also said in the past that his career would have ended pretty soon after it began if the costs were the same back when he was a junior in karting to what they are now.

Without Hamilton, Schumacher and Vettel, F1 loses the winners of a combined 18 world championship over the last 27 years.

The backing of billionaire fathers

That is not to say current drivers blessed with substantial financial backing throughout their lives do not deserve their seats.

Drivers like Lance Stroll – who surprisingly achieved pole position for the Turkish Grand Prix – and Nicholas Latifi both received the financial backing of their billionaire fathers.

Indeed, in the case of Stroll’s father Lawrence, he bought the F1 team for which his son drives.

Despite a string of disappointing finishes recently, Stroll took his team’s only podium finish in 2020, at the Italian Grand Prix. The podium was also the second of his career, having recorded a podium finish as a rookie with his previous team Williams F1 at the 2017 Azerbaijan Grand Prix.

Stroll has indicated he tries to ignore criticisms of an apparent easier route to the top, saying: “I’ve heard all the noise and heard it my whole life to be honest, so I stay in my little bubble and keep the people that really matter close to me and the rest is just background noise. I just try to do my talking on the track.”

Rookie driver Latifi is striving to make his mark while driving one of the slowest cars on the 20-car grid. Yet, despite this, he has twice finished 11th – one place away from a points finish.

Mercedes team principal Wolff says that drivers like Stroll face “stigma” because of their wealthy background even when they have the results to back up their selection.

Referring to Stroll, Wolff said: “He won the Italian F4 championship, won the European F3 championship, has been on the podium twice, and has qualified for the first row in Monza in the rain.

“I don’t think we can say just because his father is a billionaire that he’s not here on merit, right? It’s even more impressive that a kid with that environment chooses one of the most competitive sports in the world.”

‘Born into the sport’

It isn’t just Stroll and Latifi who have never had to struggle financially. The father of McLaren’s Lando Norris, 21, retired at the age of 36, having sold his pensions company and amassing a fortune worth a reported $250 million.

And many of the sport’s other young talents were effectively born into the sport.

Ferrari’s Charles Leclerc, 23, Red Bull’s Max Verstappen, 23, Alpha Tauri’s Pierre Gasly, 24, and McLaren’s Carlos Sainz, 26, all had fathers and other family members who competed, at various levels, in professional motorsport. That’s 20% of the current grid.

But Duncan says it is a costly sport for even those with motorsport pedigree.

“I spoke to [1996 world champion] Damon Hill earlier this year and he was telling me about the eye-watering sums that he used to have to put aside for his son when he was karting,” Duncan says of the English driver whose father was also a former F1 champion.

“He was saying he was costing him a hundred thousand [pounds] a year ($131,000).

“If a world champion, whose father [Graham Hill] won two world championships, is saying how difficult it is to have the money to be able to allow his son to race it shows you just how expensive it is and how difficult it is to get into this sport.”

Apart from Ocon, arguably only Red Bull’s Alex Albon, 24, faced challenges other young drivers have not. On his way up the ranks, he had to fight for every sponsor. His final step up to F1 was unexpected, as he had been signed to the Toro Rosso team after he had already committed to joining Formula E.

The majority of current drivers, therefore, didn’t face immediate financial difficulties when entering the sport at a young age. And, without financial backing, the door into elite motorsport – and the chance to prove one’s talent – is still closed to the vast majority in society.

What steps are being taken?

In June, F1 launched the #WeRaceAsOne initiative, and with it a new Task Force which aims to “increase diversity and inclusion in the sport.”

Initial funding of $1 million came personally from F1 Chairman and CEO Chase Carey. The sport had previously set out its goal to attract more diverse talent across technical, commercial, corporate, and on-air roles.

As part of the initiative, F1 says, in partnership with the governing body, the FIA, it hopes to create “a diverse driver talent pipeline by identifying and systematically eliminating barriers to entry from grassroots karting to Formula 1.”

The FIA also donated an additional €1 million ($1.18 million) to the pot.

Asked how this money directly translated into giving people from non-wealthy backgrounds a chance break into motorsport, F1 told CNN that the sport aimed to “reflect the world in which we race.”

“That means starting from the grassroots level to remove any barriers for participation in karting, making it as accessible as possible for people from all backgrounds,” a spokesperson said via email.

“We are exploring ways to make karting more affordable and accessible and working with the FIA to develop a structured pathway to single-seater racing.”

While F1 said it hoped the initiative would “encourage people from underrepresented background” to race, the sport also wanted its efforts to have an impact beyond the track, offering opportunities “through engineering scholarships, internships throughout the organization and working closely with the teams to provide as many avenues as we can into the industry.”

Former Ferrari and Williams F1 engineer Rob Smedley is involved in another initiative, the Electroheads Motorsport karting series.

The karts used in Electroheads Motorsport offer performance parity for significantly lower running costs, meaning talent is the most important factor to being a successful racing driver.

Smedley, who is CEO of Electroheads Motorsport, says a desire for a truly meritocratic and democratic form of karting is at the heart of the series.

READ: Ella Stevens: The 13-year-old aiming to become Ferrari’s first female Formula 1 driver

“The main thing that I always talk about is democracy,” he tells CNN. “You want to democratize it because motorsport should be for the many, not for the few.”

At the lower levels of karting, open-ended budgets create a disparity in the competition, with Smedley saying costs “can tend to spiral,” even at grassroots.

“If your budget is big enough, you can buy up all of the best engine(s) and there’s other levels of performance that you can effectively procure,” he says.

That effectively creates a system where the fastest drivers will be in the fastest karts. That does not necessarily equate to them being the most talented drivers.

“The genesis of it all has to be done with the grassroots to make that more accessible to more people,” says Smedley.

“Then, the chances are that you’ve got a big catching net where you can find this talent and talent shouldn’t be defined by budget.

“Budget should be secondary, or should be more accessible at least, and it has to be talent first.

“It’s about being much more meritocratic than perhaps we are now because the barriers of entry are so big, and basically give the opportunity to the people who normally wouldn’t get it.”

Will F1 ever be more diverse?

Hamilton has said that when he does leave F1 he wants to leave behind a more diverse sport.

“I’m just trying to think about what I can do, and diversity is a continuous issue, and will continue to be an issue for a long time, and there’s only a certain amount I can do,” he said.

“I am trying to think about what it is I can actually do and work with, and how I can work with F1, rather than it just be a tick on their list of things to add to ‘we also do’ – which businesses often do, and actually have something that is really implemented and actually making an impactful difference.”

Smedley, who is also director of data systems for F1, believes the sport isn’t making empty promises with its financial pledges to increase diversity and equality of opportunity, and is doing “a brilliant job.”

“It’s [Formula 1] trying to look at every single level and look at how you make a difference, and how you make systemic change,” he says. “We’re just at the start of the journey, so hopefully more and more fantastic things continue to happen.”

Duncan agrees, saying: “As it stands, the current system is still in place and it is costing parents tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of pounds a year to get their children in a position to be able to go racing.

“That’s ruling out pretty much most of the population because most people don’t have that cash just lying around. So there needs to be a change.”

However, Duncan does not believe change will happen soon – unless drastic action is taken.

“I can’t see anything really changing for the next generation at least,” he says.

“We saw someone like Lewis come through as a young Black guy in 2007. It’s now 2020 and the makeup of the grid is pretty similar to how it was when Lewis started.

“So, although he’s been a trailblazer, it hasn’t exactly paved the way for similar kids in a similar position to make it into F1.”

Smedley is more confident than Duncan that there will be another working-class driver achieving excellence in F1, saying the sport’s commitment to increasing diversity and opportunity has “gathered at an alarming pace” in the past two years.

“I think that the time is right for change and the time is right for the systemic change,” he says. “But it’s got to be that systemic change. You’ve got to change the system if you’re going to actually move the needle.

“The next Lewis Hamilton, or the next person of color either running a team or winning a world championship … you’ve got to have that change for that to be effective. But I’m convinced that it will happen.”