An Australian soldier appears to hold an Afghan child’s head against a backdrop of their two national flags, threatening to slit the youngster’s throat with a bloody knife.

The child’s face is horrified. The soldier has a cruel grin.

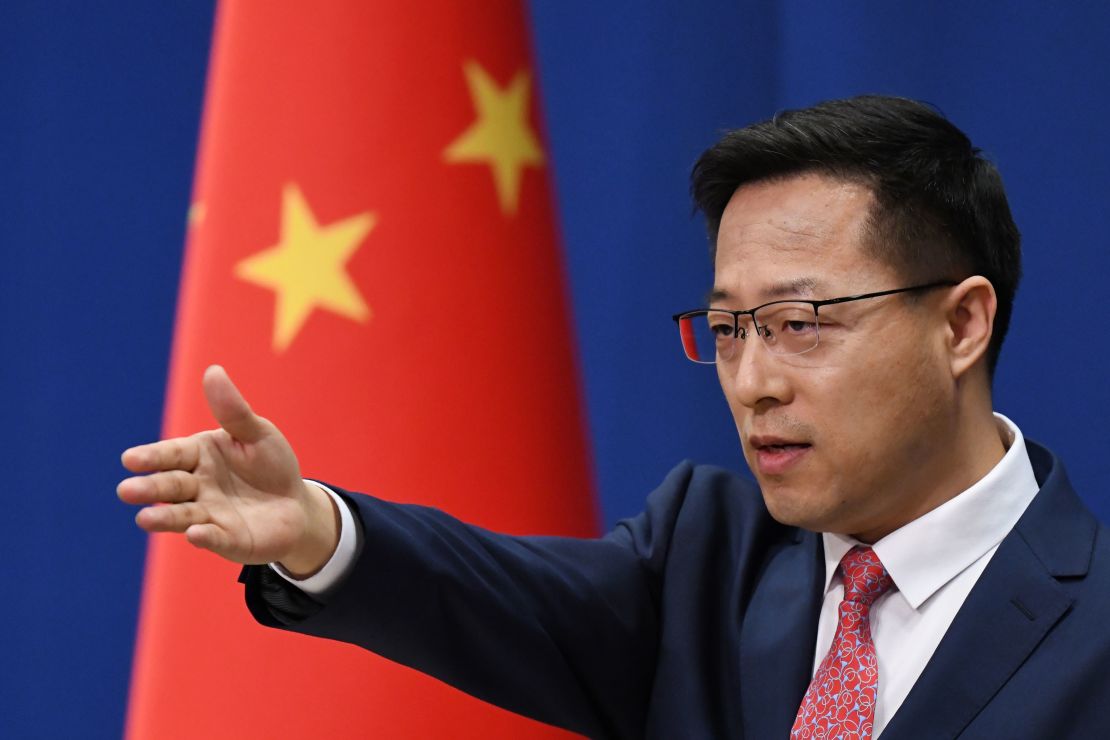

The illustration, which the Australian government has called “repugnant,” first received global attention Monday when it was posted on the verified Twitter account of Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian. When Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison demanded an apology, the Chinese government refused.

It comes after a long-awaited official report released on November 19 alleged that elite Australian forces killed 39 civilians and prisoners during the war in Afghanistan.

At first glance, the image appears to be part of a growing diplomatic clash between the two countries.

Relations have been frosty for years but deteriorated further this year after Morrison in April called for an international inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic. The Chinese government dubbed Morrison’s proposal “political manipulation.”

But it isn’t just about Australia. Experts say it bears the hallmarks of a long campaign by Beijing to distract from its own human rights abuses and polish a narrative that, unlike the US and its allies, the Chinese government is interested only in peace and non-intervention with the international community.

“It’s certainly aimed at Australia … but it is also aimed at telling the world the terrible things that the US and its allies do around the world,” said Bonnie Glaser, director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

It’s a message, experts say China hopes will appeal to some developing nations – especially those critical of Western military intervention in places such as Afghanistan and Iraq. In the image, the Australian soldier holding the bloody knife appears to say: “Don’t be afraid. We are coming to bring you peace.”

Publicly, Beijing’s messages to the world is that it will avoid using its military to interfere in another nation’s domestic affairs – unlike Washington. Rather than telling them how to run their country, the Chinese government offers “win-win” economic cooperation and trade.

This has been China’s stated policy for decades – Beijing has long pledged that two of the central pillars in its foreign policy are international peace and non-intervention in domestic affairs.

In a 2019 white paper released by China’s State Council, the country’s top administrative government body, Beijing stated that China would “never interfere in the domestic affairs of others.”

“China stands for the equality of all countries, big or small, strong or weak, rich or poor, and opposes the law of the jungle that leaves the weak at the mercy of the strong,” the paper said.

This diplomatic stance hopes to both protect China’s ruling Communist Party from any international attempts at interference while also trying to differentiate it from its main competitor, the United States.

“This is a theme which has been repeated over the past couple of years that is being told to a global audience. (Beijing says) China is a good partner, the US is not. China’s reliable and the US is not. China wants to help build a world which will benefit everyone, and the US is just selfish and interested in serving its own interest,” Glaser said.

While many countries will take a dim view of this, experts say Beijing is clearly hoping it will act as a lure for developing nations which might find the trade and large loans that China offers attractive – especially when it comes without the rhetoric of human rights usually pushed by the US.

As an example, China has become one of Africa’s largest creditors in recent years, lending hundreds of billions of dollars to governments to build roads, railways and ports. It’s also been promising to write off a small part of that debt as countries on the continent battle the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Chinese government also has a long history of highlighting human rights abuses committed by the United States and other Western powers to distract from its own record of human and civil rights abuses.

Since 2003, China has regularly released a human rights report specifically targeted at the US, focused on racial discrimination, gun violence and the gap between the rich and poor in America. In November, amid a growing feud with Australia, a Chinese embassy official told local media he would raise Australia’s record on indigenous peoples’ rights and aged care at international bodies.

Elaine Pearson, Australia director for Human Rights Watch, said the only time her organization heard Chinese officials quoting their reports was when they related to the US.

“Now we’re seeing that pattern of selectively calling out human rights violations also applying to Australia,” she said.

While Pearson said the allegations against Australian SAS soldiers in Afghanistan were very serious, she added it was “quite a surprise” to see China calling for action on the subject. In the past year alone, the Chinese government has faced international criticism over allegations of mass imprisonment and re-education of Muslim minorities in the western region of Xinjiang and an ongoing crackdown on civil rights in the financial hub of Hong Kong.

Beijing has defended its actions in both cases. The Xinjiang government has repeatedly denied allegations that it is holding up to two million Muslim majority citizens in re-education centers, saying instead that it is providing vocational training as part of a deradicalization program.

In Hong Kong, Beijing holds that the city is part of China and how it handles it is their own domestic affairs.

“It’s breathtakingly hypocritical for China to be talking about accountability and the need for perpetrators to be held to account,” Pearson said.

It is unlikely that this particular image was part of a specific disinformation campaign or a considered strategy. China does not have a sophisticated internet propaganda presence like its political ally Russia, which also called out Australia in the past week for its alleged actions in Afghanistan.

Australia’s trade minister, Simon Birmingham, said on ABC News Australia that the government had shown “degree of accountability and transparency through the review we have undertaken … that is sorely lacking in a number of other countries.”

But the post follows broad themes which the Chinese government has encouraged and promoted particularly in recent years through “Wolf Warrior” diplomats like the original poster Zhao, a new breed of foreign policy official who regularly hit back hard on social media and any perceived criticism of China or the Communist Party.

What’s more, the virulent reaction to the image and the widespread coverage of the controversy may have drawn even more attention to allegations of Australian war crimes in Afghanistan, a result which will likely be welcomed by the Chinese government.

“How many people knew about the report before? Well many more people know about it now because of this image,” Glaser said.

In a press conference on Monday, Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying bluntly rejected Australian PM Morrison’s call for an apology.

“The Australian side has been reacting so strongly to my colleague’s tweet. Why is that? Do they think that their merciless killing of Afghan civilians is justified but the condemnation of such ruthless brutality is not?” she said.

Hua then combined her refusal to apologize with a callback to the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, which Beijing has often referenced in its reports on human rights in America.

“Afghan lives matter,” she said.