Editor’s Note: Gene Seymour is a critic who has written about music, movies and culture for The New York Times, Newsday, Entertainment Weekly and The Washington Post. Follow him on Twitter @GeneSeymour. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. View more opinion at CNN.

Someone once asked me why I watched so much network news when I was growing up. I replied that it was the early 1960s – I had to keep watching because I was afraid I’d miss something if I didn’t.

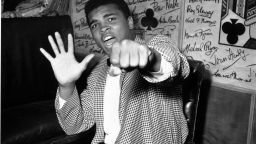

This was especially true in 1964, a year significant from the start: it began with a president no one expected in office only a year before. And that was January. The next month, the pop phenomenon known as the Beatles came to America with a thunderous, exhilarating rush. And by the end of that month, in Miami, another phenomenon named Cassius Clay, in his own words, “shook up the world” by toppling Sonny Liston from the heavyweight boxing championship, an “upset” in almost every sense of the word.

Now streaming on Amazon Prime and playing at select theaters, “One Night in Miami,” the Regina King-directed adaptation of a stage play written by Kemp Powers, imagines a meeting after that fight where the champ soon to be known as Muhammad Ali (Eli Goree) celebrates his unlikely triumph with Black Muslim minister Malcolm X (Kingsley Ben-Adir), football great Jim Brown (Aldis Hodge) and singing star Sam Cooke (Leslie Odom Jr.) in a racially segregated Miami hotel.

For viewers like me who were alive and aware of events in those turbulent years, watching King’s movie is not only a thrillingly plausible rendering of four African American icons poised at the crossroads of their respective lives. It also renders a moment of reckoning in the nation’s history where its heritage of racial discrimination was being openly confronted, from the halls of Congress to America’s streets. It seems almost an eerie convergence that “One Night in Miami’s” premiere comes at a similar, even more nerve-wracking moment in our history of race relations.

Yet, White racism oddly sits along the edges of the movie’s action, save for the condescension and dismissal Cooke receives at a performance before a mostly White crowd at the ritzy Copacabana nightclub and another moment early in the film when Brown, the greatest fullback in pro football history, visits his birthplace at St. Simons Island in Georgia, en route to Miami.

He drops by a mansion belonging to a White man named Carlton (Beau Bridges), whom he knew in childhood. Carlton is all smiles and approbation on his front porch, extolling the prodigal hero for having completed a record-setting 1963 NFL season of 1,863 rushing yards. Carlton then says he has to go back inside to move some heavy furniture. When Brown offers to help, Carlton, barely missing a beat in their conversation, assures him it’s not necessary and besides, “We don’t allow n***ers in the house.”

If you know anything about Jim Brown’s reputation for seeming indestructible and unconquerable, you’d think nothing could ever hurt him – until this moment. And yet something about Hodge’s demeanor in the role at that moment registers … not anger, exactly, but a watchful resignation. It’s shock without surprise over the way he’s been treated, similar to how many African Americans today view the resurgence of White supremacism in public spaces. A sentiment that says at once, “The more things change …” and “So what now?”

This, in a sense, is the essential question posed by “One Night in Miami”: How do Black people negotiate lives for themselves in the face of White racism that seems never to go away – no matter how many laws are enacted, political victories won or yards gained on the gridiron?

For Cooke, one of the most popular singers of the emergent soul-music era, it’s about securing ownership over the terms of his career, where he performs and what he creates. Malcolm X is skeptical that Cooke can achieve this goal by actively continuing to seek greater “crossover” appeal with White as well as Black audiences. Brown backs Cooke on this as he is starting to think he should stop lugging a football through tacklers for pay and put his good looks before movie cameras. And aren’t they doing what Malcolm has urged Black people to do all along? To seek economic independence and self-determination independent of White expectations?

But Malcolm had his own issues with independence. At this point in his life, he was estranged from the Nation of Islam and very close to breaking off his relationship with the organization. Clay, meanwhile, was about to publicly declare himself a Black Muslim and change his name to Muhammad Ali.

In the film, their complex fates seem to clash with each other. And yet, the film’s power comes in showing in retrospect how there can be many ways for Black people to seek and find their personal autonomy, no matter what the odds.

They didn’t all get what they wanted. The movie mentions at the end that Malcolm would be assassinated a year later. But it doesn’t mention that in December of 1964, Cooke would be shot to death at age 33 by a motel manager in an incident still shrouded in mystery.

Also not mentioned at the end: Ali’s future victories and vicissitudes in the ring and his refusal to enter the draft for religious reasons were ahead of him, while Brown opted to leave the NFL for Hollywood and a lucrative film career. As part of his ongoing activism, Brown also organized other Black athletes in support of Ali’s anti-draft stance.

These details are illuminating, but maybe it’s not necessary to have all this information trailing you at the end of “One Night in Miami.” The actors’ performances are altogether superb at making history come alive, in playing these four troubled, but determined men who still have much to teach Black and White audiences alike how best to cope with the seemingly unstoppable monster of racism and injustice.