For the Democratic left, President Joe Biden’s mammoth victory on Covid relief has inspired new hope of rebalancing America’s increasingly unequal economy.

Nothing will test that hope more severely than Biden’s goal of reinvigorating the labor movement as a way to do it.

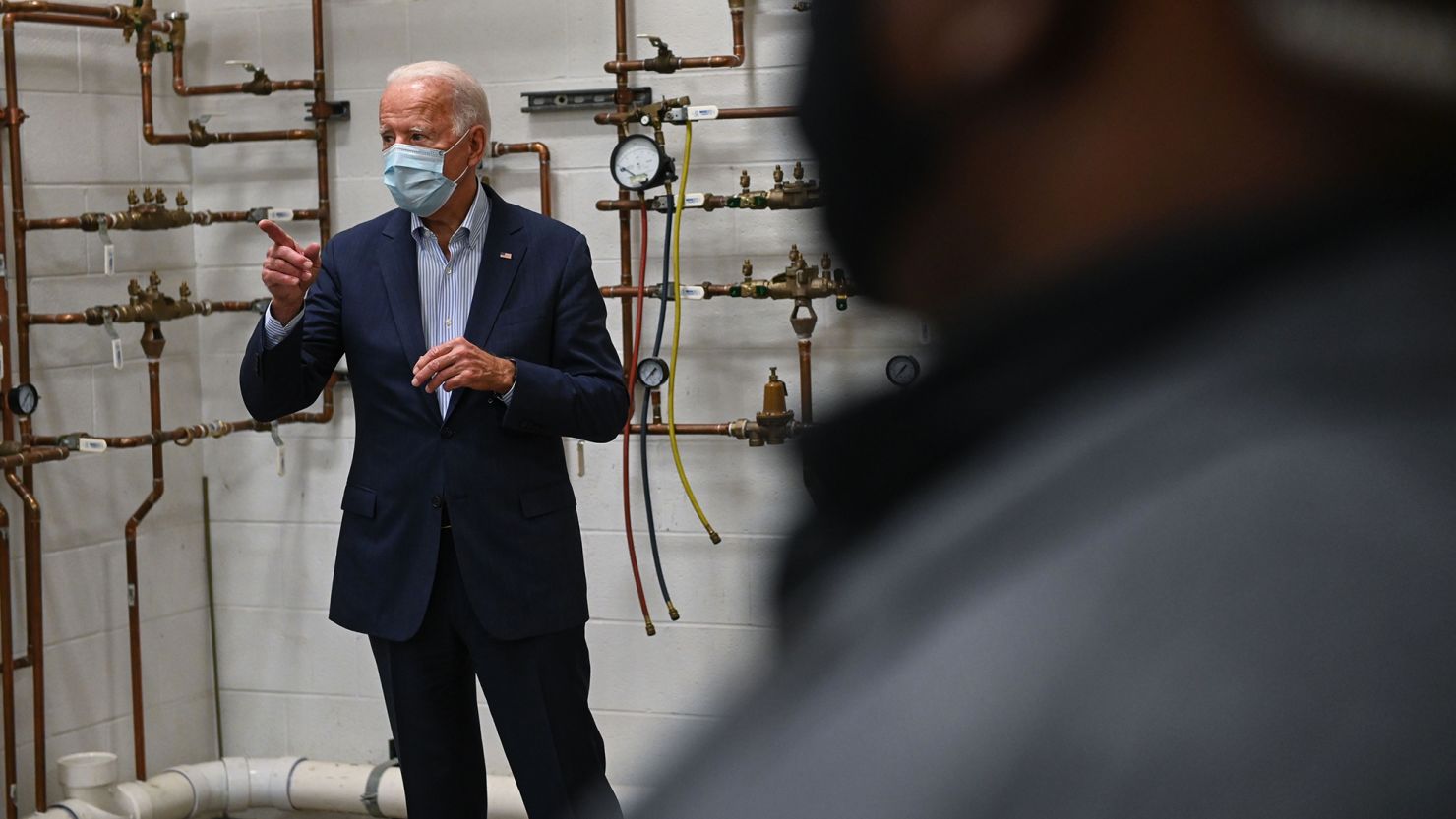

His aspiration to be “the most pro-union president you’ve ever seen” stems from his upbringing in post-World War II Scranton, Pennsylvania, where he witnessed the early stage of Rust Belt decline. Labor movement experts see early evidence of commitment in a recent video he recorded affirming the right to organize as Amazon workers in Alabama vote on whether to form a union.

“Arguably the most pro-union public statement by a president…in the entirety of American history,” tweeted Erik Loomis, a labor historian at the University of Rhode Island.

“Nothing like it before,” agreed Nelson Lichtenstein, who directs the Center for the Study of Work, Labor and Democracy at the University of California/Santa Barbara.

Biden's First 100 Days

The question is whether even a supportive president can reverse the decline in union power that economists say has helped hollow out America’s middle class. Neither organized labor nor sympathetic politicians have managed to do that for decades.

Labor union membership peaked in the 1950s, as Biden became a teenager, at just over one-third of the workforce. Ever since, an interconnected array of economic, cultural and political factors has driven that proportion down to just over 10% overall, and even lower among private-sector workers.

The decline, propelled by business executives and conservative politicians who consider unions a drag on profits and growth, has occurred in advanced economies around the world. Republican President Ronald Reagan punctuated it in the US by firing striking members of the air traffic controllers union in 1981.

But Democratic commitment to the union cause has also waned with labor’s dwindling power. For votes and campaign donations, the party’s candidates have increasingly relied on more affluent, socially liberal professionals and rising economic sectors such as Silicon Valley.

Accommodating the imperatives of globalization, Democratic Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama backed major trade expansion agreements. Biden himself voted for both the North American Free Trade Agreement and normal trade relations with China.

Recent union-backed attempts to boost worker pay, safety and organizing have made only limited headway.

The Clinton administration’s “ergonomic” regulation to protect workers from repetitive stress injuries got rolled back under President George W. Bush. “Card-check” legislation permitting union elections by signature card rather than secret-ballot election foundered in Congress under Obama.

Trump diluted Obama-era regulations expanding eligibility for overtime pay. In a ballot initiative last November, Californians voted to let ride-share companies classify drivers as contractors rather than employees with job benefits.

Biden presents an opening

Yet each of the two most recent presidents, in different ways, highlighted contemporary working class struggles. Trump appealed most emphatically to the cultural resentments of blue-collar Whites.

Biden invokes the economic plight of workers across racial lines. Union leaders say that presents an opening with Democrats now controlling Congress and the White House.

“You cannot fix inequality of wealth until you fix inequality of power,” said AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka. “Of all the presidents I’ve been around, Joe Biden understands the importance of collective bargaining in restoring the balance.”

So far, Biden has fired the Trump-appointed general counsel for the National Labor Relations Board and signed executive orders bolstering workplace safety and wages paid on federal projects. He shielded teachers unions from pressure to reopen schools before educators get vaccinated.

His Covid relief bill is sending $350 billion in aid to state and local governments, diminishing the threat of layoffs among unionized public employees. It’s sending $86 billion to bail out financially strapped union pension plans, safeguarding benefits for more than 1 million retirees.

Biden hasn’t joined Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, a 2020 Democratic rival, in backing legislation to let workers select 40% of directors on corporate boards. But he has called for doubling the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, hired a raft of left-leaning economic advisers and nominated former union President (and Boston Mayor) Marty Walsh as labor secretary.

White House officials say it all represents a chance to enhance labor’s clout. They acknowledge modest expectations on lifting union membership.

“We’re not going to get to one-third overnight,” said Seth Harris, deputy director of the National Economic Council and previously Obama’s acting labor secretary. “We’re not going to get to 20% overnight. But growth is possible.”

Biden backs the legislative answer favored by congressional Democrats. The Protecting the Right to Organize Act even drew five Republican votes as it passed the House last week.

But its only realistic chance of enactment lies with ending the Senate filibuster, which requires 60 votes to advance legislation. Democrats have just 50 senators.

“I’m not sure that it’s possible to get 10 Republican votes for the PRO Act,” said American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten.

Pro-labor lawmakers insist Biden can make progress by shifting public attitudes even without the legislation. In an Oval Office visit, Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio thanked the new President for merely uttering the word “union” so often.

“Just like Trump’s racism made it more likely racists would speak up,” Brown explained, “Biden’s speaking about unions has really made people sit up and think, ‘This is a really important part of our country.’ “

The Amazon union vote, which concludes March 29, will provide one early measurement. A breakthrough at the tech behemoth, labor advocates say, would be the modern equivalent of organizing unions at manufacturing titans Ford and US Steel a century ago.

The effort drew an unexpected endorsement last week from conservative Sen. Marco Rubio, a Florida Republican who’s a potential 2024 presidential hopeful. But repeated disappointments still temper labor’s expectations about the outcome.

“I wouldn’t exactly call it optimism,” observed Loomis. “We don’t allow a lot of optimism.”