Editor’s Note: Tom Zoellner is the co-author of Paul Rusesabagina’s autobiography An Ordinary Man. Keir Pearson is the Oscar-nominated co-writer of the film ‘Hotel Rwanda.’ The views expressed here are their own. Read more opinion at CNN.

Rwanda’s journey from its 1994 genocide to a model of orderly development made it a go-to country for those who want to invest in an African success story, taking in hundreds of millions in new overseas investments each year and making it one of corporate America’s ideal places for charitable donations. But the love affair between the United States and Rwanda’s hardline president Paul Kagame, should be seriously reconsidered after 27 years of systemic human rights abuses.

To name the alleged abuses is to name what’s typical of despots everywhere: election-rigging, a captive judiciary, a well-oiled propaganda machine that silences truth, and the assassination of opposition leaders, journalists, and regime critics at home and abroad. The Rwandan government has consistently denied involvement in attacks against its critics, but after opposition figure Patrick Karegeya was killed in a South African hotel room in 2014, Kagame’s Minister of Defense was quoted as saying, “When you choose to be a dog, you die like a dog, and the cleaners will wipe away the trash so that it does not stink for them.”

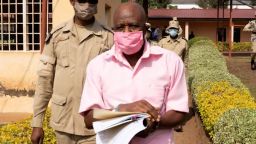

Today Kagame is facing a fresh round of scrutiny over his latest transgression: the alleged kidnapping of Paul Rusesabagina, the protagonist from the film ‘Hotel Rwanda,’ a US permanent resident and a widely-admired humanitarian figure. The Rwanda government has denied that he was kidnapped, but Rusesabagina described himself as a hostage when he appeared in a Kigali court last month on terrorism charges.

The charges are widely seen as trumped-up and the outcome of the trial should not be in doubt. Rwanda’s justice system pivots on a single principle: the will of Kagame. This was underscored this month when Rusesabagina told the High Court that he will no longer attend his own trial because “I don’t expect any justice in this court.” He has good reason to believe so, saying he’s been denied access to his own lawyers for months and after six months he still hasn’t been allowed to examine the indictment and 5,000+ case files that detail the charges against him. The court’s denial last week of motions brought by Rusesabagina and his attorneys has also denied him the right to cross-examine witnesses or review evidence.

Kagame has long harbored animosity against Rusesabagina, who gained international fame and was awarded the US Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush in 2005 after the movie “Hotel Rwanda” depicted his acts of wily heroism in shielding 1,268 people within the Hotel des Mille Collines, a luxury hotel he managed in the heart of Rwanda’s capital, during the genocide. Rusesabagina used his platform to make increasingly vociferous criticisms of Kagame’s regime, a stance that turned him into an official pariah in his home country.

Kagame escalated a smear campaign against Rusesabagina, falsely claiming that he funded terrorists allied with a fringe group in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The case went nowhere, a sign of its lack of credibility.

But dictators don’t quit. A special chamber of Rwanda’s High Court found this month that Rusesabagina was “tricked” when he boarded a private plane in Dubai last August.

In a set-up out of an espionage novel – his family called it a kidnapping, which Kagame has disputed – the chartered flight, supposedly headed to Burundi, landed in Kigali instead, where Rusesabagina was arrested. In our view, this was a gross violation of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

Kagame once again leveled “terrorism” charges against Rusesabagina laid out in an indictment that hangs on hearsay, inference, and witness testimony that is too easily coerced in Rwanda today. If this evidence was any good, it would have been submitted to Belgian and US authorities for extradition proceedings as Kagame has done in the past.

Those who have looked closely at Rusesabagina’s plight have come to uniform conclusions. In December of last year, 37 members of the US Congress sent a letter to Kagame condemning the kidnapping and demanding Rusesabagina’s release. On February 11, the European Union Parliament passed a resolution stating the same. But while Rusesabagina’s unlawful detention may be on the radar of the Biden administration, the President made no public protest about it even after Rwanda’s Justice Minister said in an Al Jazeera interview that his deputies confiscated Rusesabagina documents protected by attorney-client privilege, once again proving that the proceedings are a sham.

Given the fate of many political prisoners in Rwanda, Rusesabagina’s chances of survival may be slim. “You can’t betray Rwanda and not get punished for it,” Kagame is reported to have once chillingly told a prayer meeting. If the Biden administration wants to announce to the world that America’s concern for human rights is back, a good place to start is by demanding the freedom of this global humanitarian figure. The US Agency for International Development last year announced a plan to give around $609 million to the country over the next five years. Curtailing this USAID money would be a powerful piece of leverage.

Rwanda became a model of post-genocide recovery because of its polished image, but the time has come to look under the dictatorial fa?ade. Kagame has already made a clear point to anyone who challenges him: If I can do this to Paul Rusesabagina, just think what I can do to you.