It was meant to be a curtain-raiser for thousands of sports fans, a celebration of Japan’s recovery from nuclear disaster 10 years ago that would showcase a country emerging strongly from years of economic gloom.

But the Grand Start of the Olympic Torch Relay in Fukushima was closed to the public on Thursday, as members of Japan’s women’s football team prepared to kick off the flame’s 121-day domestic journey to Tokyo.

Amid the pandemic, anyone not among the 300 invited participants and officials could only watch a livestream of the event at Fukushima’s J-Village National Training Center.

In 2011, the site was used as an operational base for relief efforts following the massive earthquake and tsunami that triggered a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant on March 11 that year. Tokyo 2020 organizers chose Fukushima as the torch relay’s starting point to highlight the region’s recovery from the triple disaster. From there, 10,000 runners will carry the torch through Japan’s 47 prefectures in a show of national unity.

But in recent weeks, the positive narrative has stalled. Some Fukushima residents argue the region has far from recovered. Several celebrity torchbearers, who were expected to attract large crowds along the relay’s route, have pulled out of the event, citing concerns over Covid-19.

In February, the western Shimane prefecture even threatened to cancel torch relay events if coronavirus cases didn’t fall, according to local media reports, which said a decision would be made in April.

Last week, Olympic organizers said the postponed 2020 Tokyo Games, now scheduled for July 23 to August 8, would go ahead without any overseas spectators. The Paralympics, from August 24 to September 5, would also not be welcoming traveling fans, they said.

With costs and logistical challenges mounting amid the pandemic, public support for the blockbuster sporting event has fallen to an all-time low in Japan. Earlier this year, a poll by public broadcaster NHK showed 77% of those surveyed want the Tokyo Games either canceled or postponed further.

As the pandemic continues to roil the world and organizers grapple with the complexities of holding the mega sporting event later than planned, many are asking if the Olympics have lost their luster.

Tarnished spectacle

At its core, the modern Olympics – first held in Athens in 1896 – symbolize peace, harmony and solidarity between nations, according to organizers, the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

But it would be hard to find an example of an Olympic Games free from political, economic or cultural scandal, according to Lee Jung-woo, an expert on sports diplomacy and international relations at the University of Edinburgh.

Lee cites as examples the Nazi propaganda-tarnished 1936 Berlin Olympics, and Mexico City in 1968, when the Games followed a military massacre of unarmed civilians protesting against the event being held there.

He also highlighted Montreal, where taxpayers took three decades to pay off the debts for hosting the 1976 Summer Games.

Pandemic problems aside, Tokyo 2020 has also been hit by scandals, including an allegedly plagiarized Olympic logo to the resignation of the organizing committee president over sexist comments about women.

Another issue is that former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe – who resigned in August – initially intended to use the Olympics as a platform to build his reelection campaign, tainting the public perception of the Games from the start, according to Simon Chadwick, director of Eurasian Sport at Emlyon Business School in France.

“I don’t think there was ever any popular consensus or agreement across Japan that the country needed to host the Olympic Games,”’ he said.

In Fukushima, feelings toward the Olympics are mixed.

The relay is a moment of personal triumph for Takayuki Ueno, 46, a torchbearer from Minamisoma city whose 8-year-old daughter, 3-year-old son, and parents died in the 2011 tsunami. “I am going to run with a smile, so that my parents and children that I lost won’t worry about me,” he said.

High school student, Ryoji Sakuma, was only able to return to Katsurao village three years ago when evacuation orders lifted. The 16-year-old torchbearer helps out on his family’s dairy farm and said he wanted to show the world how much Fukushima had recovered, and that, despite rumors, its produce is safe to eat.

But Saki Ookawara, spokeswoman for an organization that advocates for evacuees displaced by the nuclear meltdown, said the government is using the Olympics as a political tool to show Japan has overcome repercussions of the triple disaster, when that is not strictly the case.

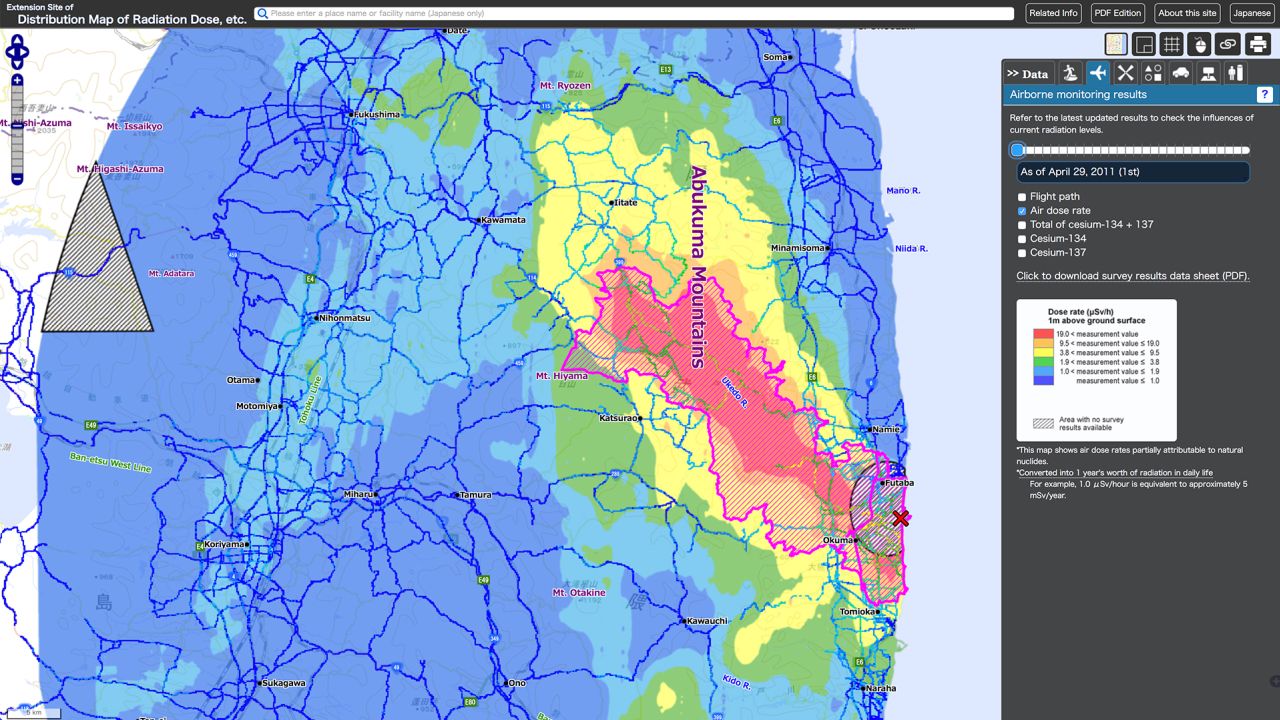

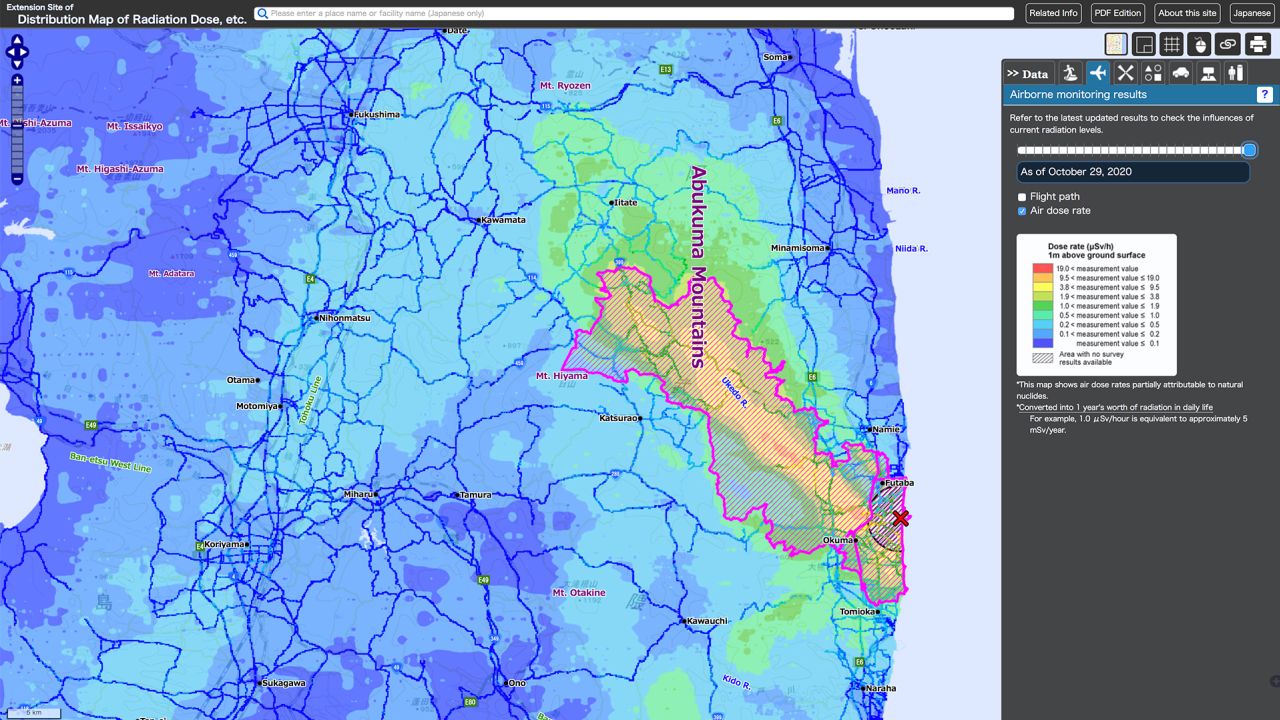

Although many communities have rebuilt, there are as many as 35,703 nuclear evacuees still unable to return to their homes in Fukushima prefecture as of this month, according to the local government. “I don’t understand why Japan is hosting an Olympics when the nuclear disaster has not been fully resolved,” said Ookawara.

Spotlight on Japan

The entire symbolism of the Olympics and torch relay has changed amid the pandemic, according to Barbara Holthus, deputy director of the German Institute for Japanese Studies.

“The original idea for Tokyo was to show the world how cool Japan is – it was an opportunity for the country to reimagine itself and to come together as one. Forty million visitors were expected to visit Japan in 2020 to give the country an economic boost – but none of that is happening. The Olympics are failing in all instances,” said Holthus.

The Tokyo 2020 Olympics are already the most expensive Summer Games ever, with the one-year postponement of the event pushing the cost up at least $15 billion to total $25 billion, according to Japanese media reports.

Pulling off the world’s most complex sporting event, involving more than 11,000 athletes from over 200 countries who must be kept safe, will also be no easy feat.

Organizers are now racing to determine how Tokyo can stage the event safely, especially considering the capital only lifted its third state of emergency on Monday following a third wave of infections.

Authorities must figure out how to protect not only athletes, but also citizens of the world’s most populous metropolitan area, a daunting task considering Japan’s huge elderly population and its slower-than-expected rollout of coronavirus vaccines.

Ayako Kajiwara, a nurse who works in a hospital near Tokyo, said she hoped vaccinations would be sped up in the country to better protect the population. “Some people in Japan think the Games should be canceled (but) others have already bought tickets for events,” she said.

“For me, the Olympics represents the idea of the world coming together and I’d like to have some hope. I worry what will happen if it doesn’t go ahead as the taxpayers might bear the burden,” she added.

As Tokyo 2020 will be the first mega sporting event held during the pandemic, the health and safety measures implemented – whether successful or not – could serve as useful markers for future international sporting competitions.

“In that sense, Tokyo’s anti-coronavirus programme would be marked as a long-lasting legacy of this Olympic Games,” said Lee.

Olympic legacy

The most successful Games are those designed to leave behind a positive legacy, according to Chadwick, the sports business expert.

For instance, the Barcelona Summer Games in 1992 spurred the city’s urban regeneration as the remodeling of the waterfront development of the Olympic Village and harbor made beaches accessible to the public. Subway systems were extended and roads connecting the city were turbocharged, according to a report published in the journal Environment and Planning.

Similarly, nine years after hosting the 2012 Olympics, London has managed to draw business and visitors to Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park – a former post-industrial district in the east of the British capital.

Lee, the sports diplomacy expert, said the 2024 Summer Games in Paris followed by the Los Angeles Games in 2028 show Western democracies still want to host the Olympics.

However, as host countries and their populations factor in the high economic and environmental costs of the Olympics, it is authoritarian regimes that have embraced the Games as a soft-power tool.

“Non-liberal emerging powers tend to stage the Olympics at all costs in order to impress world audiences,” said Lee.

For instance, China had never hosted the Olympics prior to 2008. But some 14 years after hosting its inaugural Summer Olympics, Beijing will become the first city to stage both Summer and Winter editions of the Games, in February 2022 – an event, if successful, that could validate its authoritarian system, according to observers.

Future Games

In 2019, the IOC mapped out new rules that would require future bidders for Olympic host city to win a referendum at home before entering the race.

That move aimed to cut back on expensive bidding races and prevent wasteful “white-elephant” projects that cost a fortune to build but serve little purpose in the long run.

For instance, Beijing’s famous “Bird’s Nest” stadium, built for the 2008 Games at a cost of $460 million, is not widely used today.

The rule changes may also pave the way for smaller cities to join the bidding for host city, Lee said.

The IOC’s choice of Brisbane, provincial capital of Australia’s Queensland, as “preferred host” for the 2032 Summer Games, shows the direction of the Olympics has already shifted, according to Lee.

Lee said the IOC picked Brisbane because the city had already hosted the 2018 Commonwealth Games jointly with the Gold Coast, also in Queensland. “This means that Brisbane does not have to build new sporting facilities and athlete villages. This would make the Olympic Games in Brisbane a more sustainable choice than any other candidate cities for the 2032 Olympics,” Lee said.

Additionally, Australia is one of the few Covid-safe nations in the world now, and this situation may have added a more competitive edge to Brisbane’s Olympic campaign, he said.

Back near Tokyo, Kajiwara, the nurse, said last year she applied for a lottery, which covered 10 sports such as basketball, soccer, rhythmic gymnastics and track. She got a coveted ticket to watch the men’s 100-meter final. She just hopes she can still go.

CNN’s James Griffiths, Selina Wang and Joshua Berlinger contributed to this report from Hong Kong and Tokyo.