“There is a difference between being informed and getting retraumatized.”

That’s what clinical therapist Paul Bashea Williams tells himself and his clients as they struggle with the distressing images now resurfacing during the Derek Chauvin trial.

The proceeding churns up a persistent trauma. The replay of George Floyd’s final moments can feel inescapable, leaving many feeling raw, vulnerable and without relief. There are places you can turn for immediate help.

? The Suicide Prevention Lifeline —1-800-273-8255

? The Anxiety and Depression Association of America — 1-240-485-1001

? The National Alliance on Mental Illness — 1-800-950-NAMI (6264)

? The Association of Black Psychologists — 1-301-449-3082

While the evidence surrounding Floyd’s death is distressing for most audiences, it is overwhelming for African Americans — and especially excruciating for Black men who see their very humanity reflected in him.

“Sometimes you are visualizing you,” says Williams, lead clinician and owner of Hearts in Mind Counseling in Prince George’s County and Montgomery County in Maryland. 90 percent of his clients identify as Black.

In the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, and now during Chauvin’s trial, African Americans are fighting harder than ever to protect and prioritize their mental health.

And Black men and women are exhausted.

Caught between hope and hopelessness

According to Williams, his clients are continuously cycling through feelings of hope and hopelessness. While many hope for justice, they are also bracing for disappointment, one that feels familiar when unarmed Black men and women are killed by police officers.

Williams also points out the secondary trauma African Americans experience from the images and video surrounding Floyd’s death.

“It is the emotional and psychological effects experienced through vicarious exposure to the details of traumatic experiences of others,” he says.

Among the private concerns Black men have shared with Williams are “feeling anxiety around leaving the house” and “depression over not having control over one’s life.”

As the trial continues, Williams offers five tips to individualize care during the trial.

Tip 1: Create safeguards around watching the trial

“I want to give permission to people to not watch,” Williams says about the trial.

And as the nonstop coverage rolls across TV, phones and computers, he suggests setting limits. As a Black man, husband and father, the therapist practices the same care he recommends to his clients. “I had to set up boundaries to be able to show up for my son, my dad, my wife — my clients especially, who came in and were struggling.”

Williams says some struggled with not watching news coverage when Floyd was killed. Some felt as if they were letting the Black community down and not standing in solidarity.

But for those struggling to watch the trial, he suggests reminding yourself, “I don’t have to be inside the courtroom.”

And, for those feeling guilty about not watching, he recommends finding other ways to support social justice, without retraumatization. Possibilities can include political advocacy, being a listening ear for others, and donating time and money.

“We have to pay attention to ourselves and not push through because we feel like we have to be there.”

Tip 2: Acknowledge your feelings

In the midst of the trial, Williams’ also suggests taking a moment to be present with yourself and to name the feelings and experiences you may be having. To begin, you can start with this question, “What am I experiencing now?”

The answer to that question may be fatigue, headaches, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, irritability, and anxiety. Emotional and physiological responses can be helpful gauges of knowing when enough is enough.

“If I know what is happening in my environment, I can allow myself to make shifts,” he says.

Tip 3: Create community

A trusted support team is helpful in gently identifying changes you may not readily see in your mood or behavior. The therapist is clear that one’s self-care community must be grounded in relationships they can trust.

Helpful communities can flourish online through group texts and at socially distanced meetings.

Tip 4: Prioritize self-care with boundaries

In his practice, Williams helps his clients identify ways to care for their mental health in their everyday lives. One way to do this individually is to take an internal inventory of moments when you historically experienced joy.

Williams mentions that, culturally, Black individuals are often taught to care for others ahead of themselves, while balancing the pressures that come with daily life.

“We have to have self-advocacy. We have to prioritize ourselves,” he says. “And it is not selfish.”

To begin this process, Williams suggests asking yourself, “What are the things I liked growing up?” and “What are the things I like now?”

Williams says this step is often unfamiliar for men.

When asking male clients “What does your self-care look like?” he’s often met with blank stares and hesitation.

“They were like, ‘Man, I don’t know what that is,’” he says.

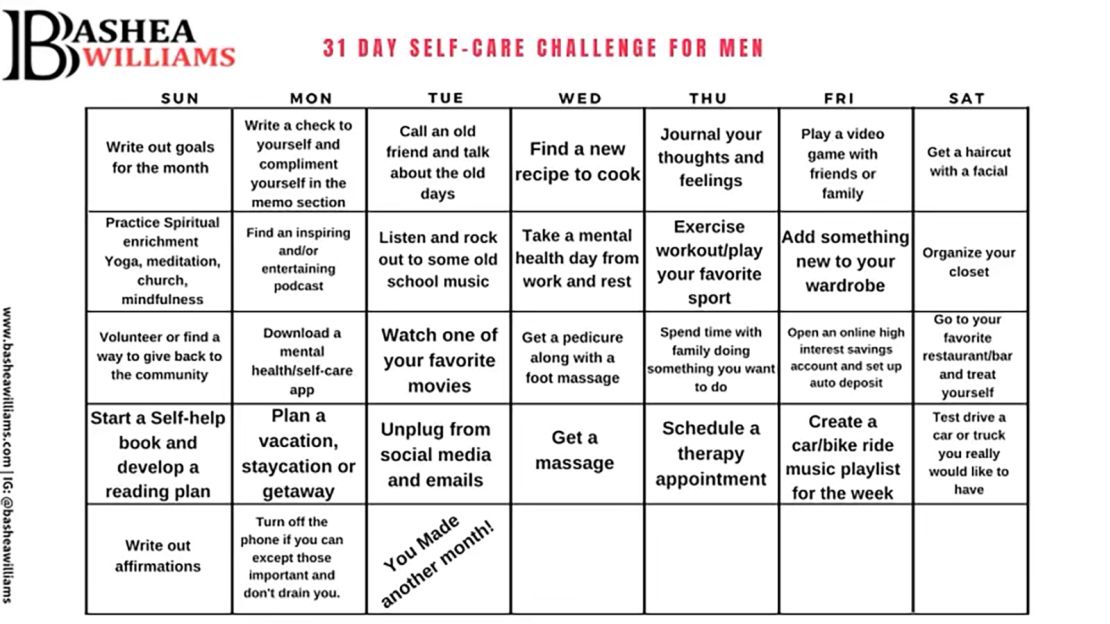

Seeing this need among his clients and social media following, Williams created a men’s self-care calendar to help men rediscover their own individual needs.

The next step is to create boundaries to prioritize needs. For example, Williams says using the “do not disturb” option on a phone is one way of “putting the responsibility on the boundary.”

“Boundaries allow you to protect yourself,” he says. “Boundaries are like a set of rules that you have in order to function, and to have healthier experiences with people, places and things.”

Tip 5: Seek Therapy

“It is important for the Black community to get into therapy,” Williams says.

He recommends finding a therapist whom you trust and who fits with you.

“Your first therapist might not fit,” he cautions.

When seeking a clinician, he encourages individuals to try out therapists. He also recommends pushing back if you feel you aren’t getting enough in sessions.

“Be empowered to find another therapist.” He says. “Say, ‘Hey, I don’t feel like I am getting what I need. Can we try something else?’”

And, if your therapist isn’t working out, Williams recommends acknowledging it and finding someone who may be a better fit.

Finding Support:

For mental health services specific to Black wellness, visit any of these organizations.

Therapy for Black Men, provides access to a growing directory of more than 100 therapists with “multi-culturally competent care” for Black men.

Black Men Heal provides a list of available African American therapists, plus resources on how to get 8 free therapy sessions. (The site acknowledges there will likely a wait-list for no-cost services.) The organization says it has provided 600 free therapy sessions.

Therapy for Black Girls is an “online space dedicated to encouraging the mental wellness of Black women and girls.” The site also offers a podcast and the option to join a “therapy for Black girls sister circle” for a monthly subscription of $10.

Also, Psychology Today offers a portal to search for African American therapists close to home by cost, location, issue, and therapy time.

And websites like Alkeme Health provides curated mental health content specific for Black and African American users. The site says it “fuses digital and wellbeing to improve your life.” On its website, Alkeme Health provides guided meditations and “live labs” where users can register to learn about practical ways to improve personal wellbeing.