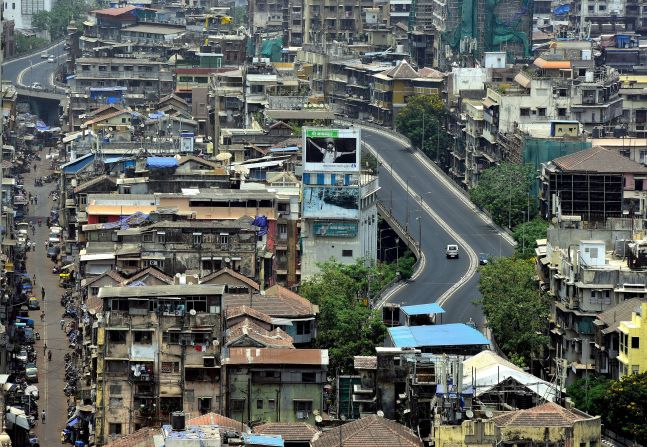

Just six weeks ago, India’s Health Minister declared that the country was “in the endgame” of the Covid-19 pandemic. On Friday, India reported the world’s highest single-day number of new cases since the pandemic began, for the second day in a row.

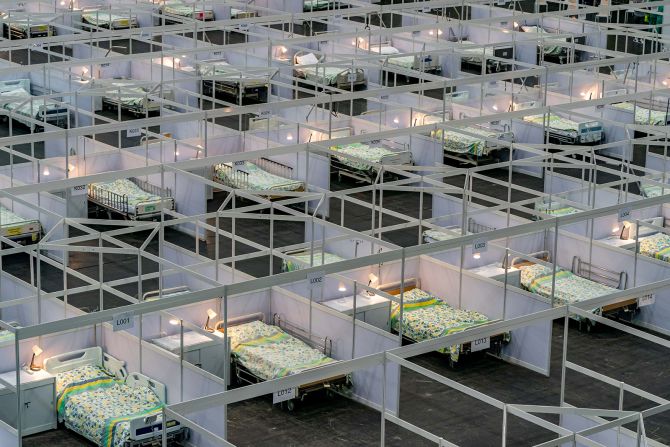

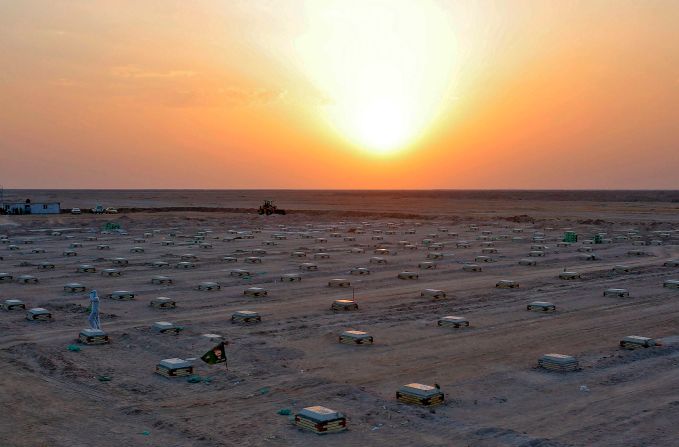

India’s second wave, which began in mid-March, has devastated communities and hospitals across the country. Everything is in short supply – intensive care unit beds, medicine, oxygen and ventilators. Bodies are piling up in morgues and crematoriums.

India reported 332,730 new cases on Friday, marking the highest daily case count globally. The United States is second, having recorded a high of 300,310 cases on January 2.

India’s population is roughly four times that of the US, and its daily cases still fall behind the US when adjusted for population size (in cases per million people).

But the fact remains, India’s total now stands at more than 16 million confirmed cases and nearly 187,000 related deaths, according to data from Johns Hopkins University.

“We’re going through pretty much the worst possible phase of the pandemic here,” said Chandrika Bahadur, chair of the Lancet Commission on Covid-19 India Taskforce, on Wednesday. “It has been bad for a couple of weeks, but now it’s reached a peak.”

And that peak shows no sign of falling off anytime soon. As India tumbles deeper into crisis, many are wondering: where are the country’s leaders?

State ministers and local authorities, including those in hard-hit Maharashtra, have been warning about the second wave and preparing action since February. In jarring contrast, there appears to have been a vacuum of leadership within the central government, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi staying largely silent on the situation until recent weeks.

In intermittent statements throughout April, Modi discussed the national vaccination effort and acknowledged the “alarming” rise in cases, but was slow to take containment measures besides ordering states to increase testing and tracking, and asking the public to stay vigilant.

And he continued to praise the country’s success, even as states imposed new restrictions and hospitals began running out of space. “Despite the challenges, we have better experience, resources and, also the vaccine,” his office said in a press release on April 8. Two days later, he celebrated 100 million doses of vaccine administered nationwide, tweeting that they were “strengthening the efforts to ensure a healthy and Covid-19 free India.”

It wasn’t until Tuesday that Modi finally emphasized the urgency of the situation and laid out new measures in a late night address to the nation. “The country is again fighting a very big battle against Covid-19,” he said. “A few weeks ago, the conditions had stabilized – and then came the second wave.”

But by then, India’s outbreak was already the world’s biggest in terms of absolute daily numbers. Nearly 28% of all new cases worldwide in the past week have come from India, according to the World Health Organization.

The descent into crisis, and the administration’s scramble to respond, has shown “a complete arrogance, hubris of a kind, in terms of decision making,” said Harsh Mander, writer and human rights activist, on Thursday. “The government has completely and manifestly shown (a lack of) both competence and compassion.”

Building anger

Modi, who won a landslide re-election with his Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party in 2019, enjoys immense popularity in India. Even last year, when India’s economy was battered by a stringent lockdown that brought the entire country to a halt, Modi largely escaped the scathing headlines and crushing opinion polls that other world leaders have had to face.

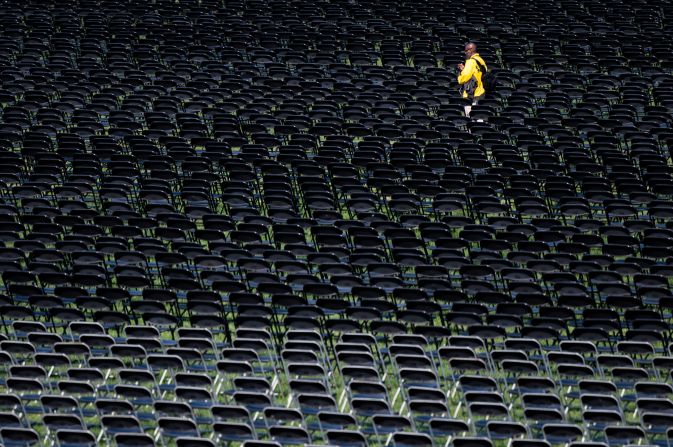

But this wave is far bigger than the last one. People are exhausted and frayed after more than a year of the pandemic. Patients and their loved ones, unable to get the necessary care, have resorted to pleading on social media for medicine and open hospital beds. And experts who cautioned for months about a potential second wave are frustrated that their warnings went unheeded.

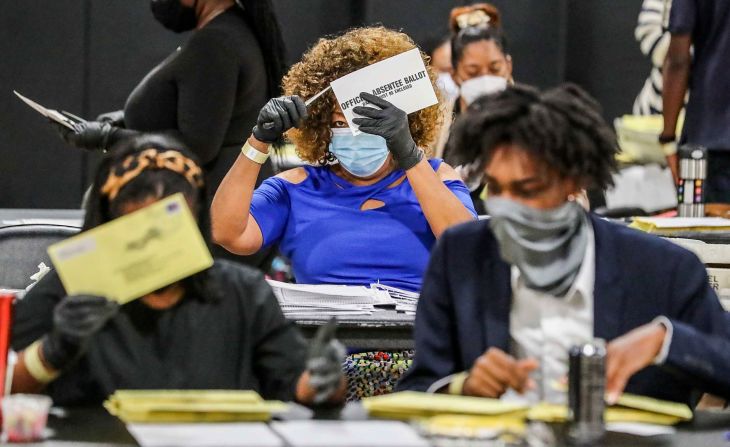

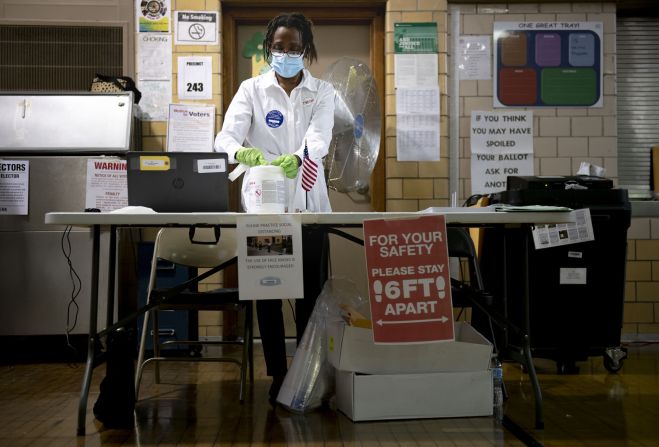

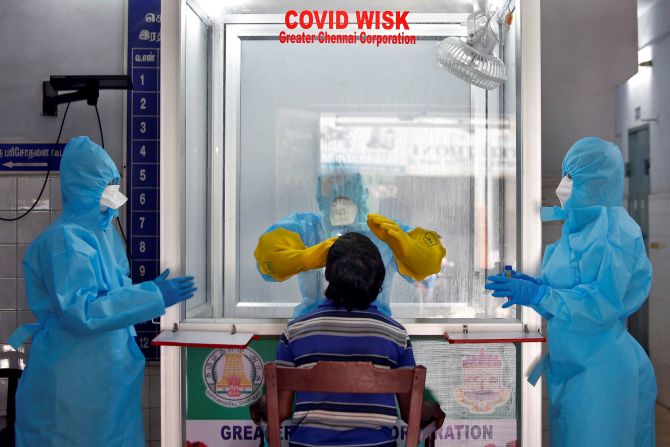

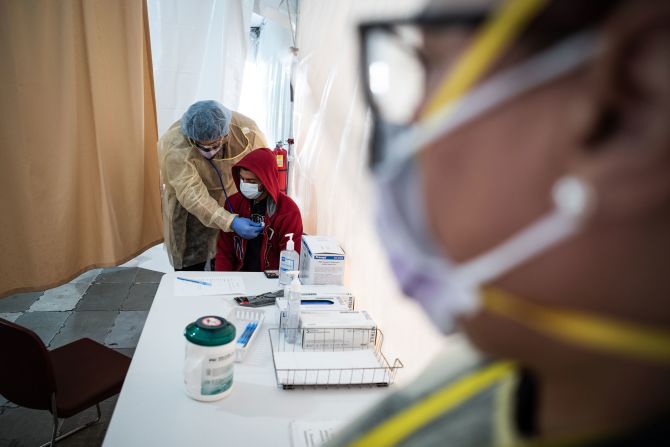

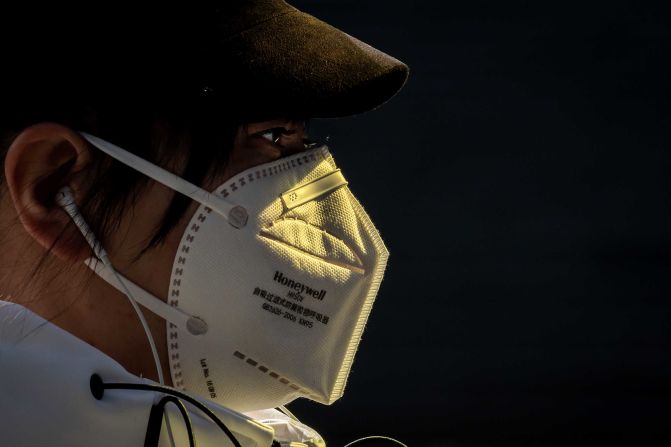

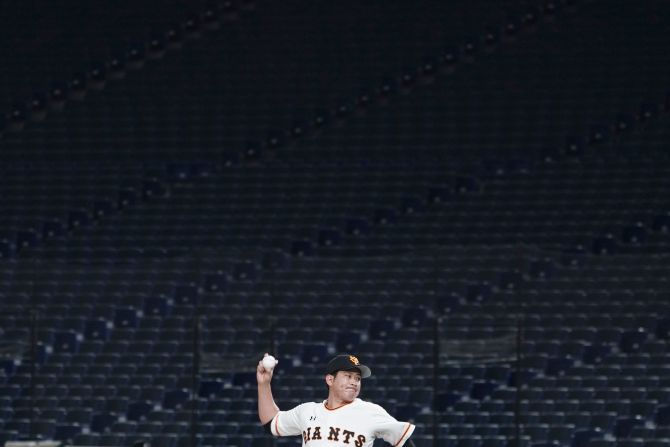

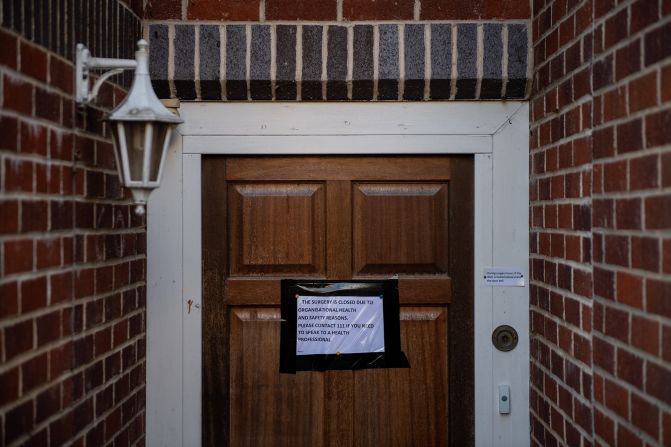

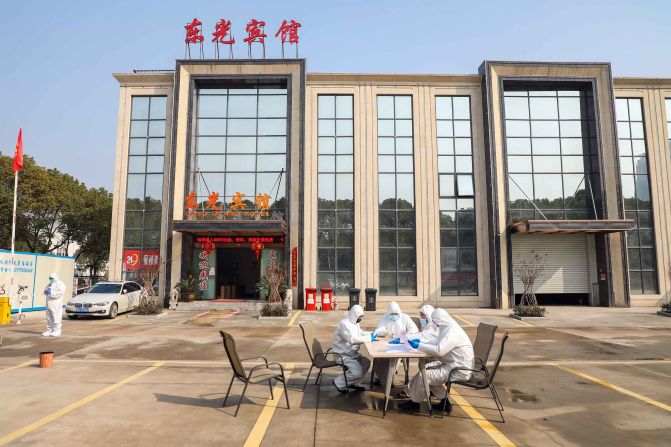

In pictures: The coronavirus pandemic

These grievances spilled over on social media in the past week. Tens of thousands of people took to Twitter with trending hashtags like #ResignModi, #SuperSpreaderModi, and #WhoFailedIndia. Political figures, including state authorities and former officials, were among the voices calling for greater accountability and criticizing the government’s handling of the crisis.

“Covid19 struggle in India is the reflection of (Modi’s) govt,” tweeted Siddaramaiah, the former chief minister of Karnataka state, on Monday. The government may have been caught off guard by the first wave, he added – but “what is the status now? The preparedness is hopeless even now!”

Mamata Banerjee, West Bengal chief minister and member of the Trinamool Congress Party, called for Modi’s resignation. “The prime minister is responsible,” she said, adding that he “has not done anything to stop Covid nor let anyone else do anything to stop it.”

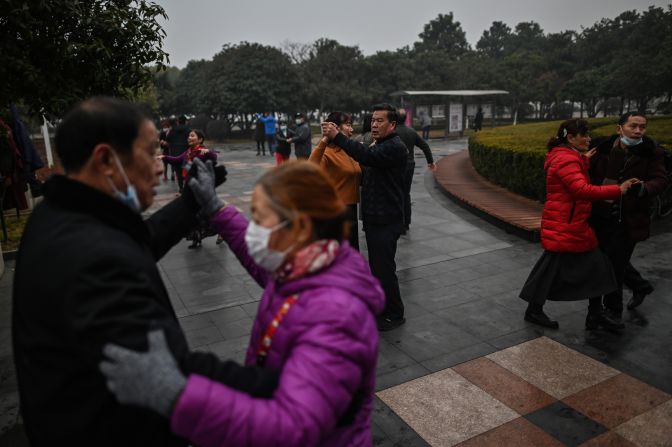

Experts and health care workers say the public let its guard down with a false sense of security after the first wave subsided, which is why the second wave advanced so rapidly – but this complacency was exacerbated by government officials like Modi and Health Minister Harsh Vardhan, who loudly celebrated the country’s apparent recovery. Leaders did little to discourage public gatherings, allowing a massive weeks-long Hindu pilgrimage to proceed with millions of attendees traveling across numerous states.

The anger has also been heightened this time by Modi flying out to hold political rallies in between meetings with his ministers about the outbreak. Four states and one union territory are holding elections for their state legislature – including West Bengal, a major battleground currently ruled by Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress Party, and which has never had a BJP government.

It has become a key focus for the BJP, and Modi has held numerous rallies in the state with thousands in attendance between March and April.

But as cases skyrocketed, several of the competing parties stepped back from the campaign trail. The Indian National Congress, India’s main opposition, announced on last Sunday it would suspend all public rallies in West Bengal. Banerjee said her party would also hold short meetings due to the pandemic.

The BJP announced it would also limit its rallies to “small public gatherings” – with a cap of 500 people. Modi was set to travel to West Bengal on Friday for a campaign event – but announced on Thursday that he was canceling the trip to instead attend high-level Covid meetings.

But Modi and the BJP’s rallies throughout March and April, and their late action, undermine his message to the public for greater vigilance, said Mander, the activist.

“There’s a blaming on ordinary people,” he said. “But what we have seen is that the prime minister has actually gathered large masses of people, none of them wearing masks and keeping any kind of distancing in political gatherings.”

Suffering on the ground

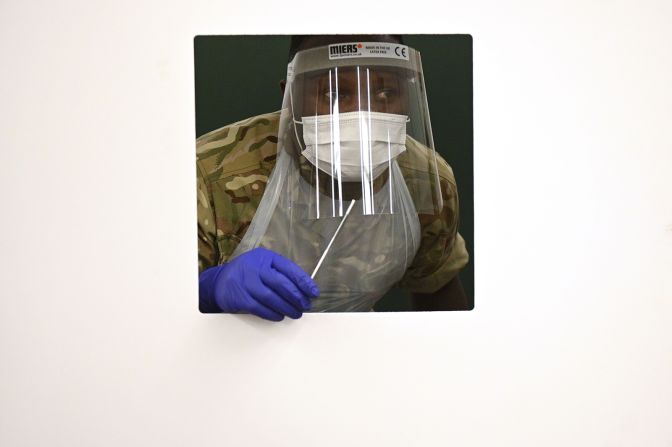

The government launched a number of measures this week, including plans for the delivery of 100,000 cylinders of oxygen nationwide, new oxygen production plants, and hospitals dedicated to Covid-19 patients.

But as states and hospitals wait for much-needed assistance, a black market has emerged to fill the gap, highlighting the lack of resources from central authorities.

Earlier this week, 22-year-old student Vishwaroop Sharma drove his critically ill Covid-positive father to a hospital in Delhi, but there were no beds or oxygen available. They were forced to wait outside, where “nothing was provided, and he died in front of me, on my hands,” Sharma told CNN.

He returned home to find his mother had also been infected and was struggling to breathe. Frantic, he bought an oxygen cylinder off the black market, placed her on an oxygen mask, and drove her from hospital to hospital for several days until he finally found her an open bed 100 kilometers (62 miles) away.

The shortages are particularly damning since the country has had ample time to prepare, said Mander.

“You had a full year to do it,” he said. “And suddenly we’re finding these really criminal shortages around the country. When you start searching, you find that orders were not placed, companies have not been pressured because they’re not making supplies.”

The tragedy and desperation on the ground could potentially leave a deep, generational rift between the public and their government, he added.

“Many things broke down last year – but one of them is trust,” Mander said. India’s poorest and most vulnerable residents “believed that when things get really bad, we will be protected by our government and our employers. That trust completely broke down … You’re on your own.”

And still, Modi’s popularity could shield him from public backlash and protect his seat of power.

When Modi was re-elected in 2019, there were already “very few illusions,” Mander said. The economy was struggling, with little job creation; the farming sector was in crisis, leading to ongoing nationwide farmers’ protests. Despite these numerous problems on Modi’s plate, his Hindu nationalist policies and agenda won him loyal followers as tensions rose between Hindus and Muslims in the country.

Even now, even as thousands die each day, “none of this is seeming to weigh against the popularity of the government,” said Mander – which “can only be explained by the power” of his Hindu nationalist base.

It remains to be seen how the pandemic will affect Modi or his party in the next general election, in 2024, he said.

In the meantime, civilians devastated by the outbreak are left to grapple with fear, grief, and the sense that they have been abandoned.

“New Delhi is getting worse day by day, it’s becoming hell,” said Sharma, who returned home after finding the open hospital bed. “They are not getting anything.”

“I am totally helpless,” he added. “I am so scared, I am so terrified. I don’t want to lose my mother as I have lost my father. I won’t be able to survive if I lose my mother.”

CNN’s Aditi Sangal and Esha Mitra contributed to this report.