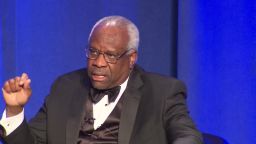

Twenty-nine years ago, less than a year after he had taken the bench, Justice Clarence Thomas joined a dissent calling the landmark opinion Roe v. Wade “plainly wrong” and an “erroneous constitutional decision.” Over the years Thomas would say Roe had “no basis in the Constitution” and call out the court’s abortion precedents as “grievously wrong.”

He also took aim at challenges to the Second Amendment, accusing lower courts and his own colleagues of thumbing their noses at the right to bear arms, calling it a “disfavored right.”

Now Thomas is 72 years old with a head of gray hair and he is awaiting a new season on a 6-3 conservative majority court. The justices have agreed to hear a case next term that critics – and some supporters – say is meant to gut Roe. They will also hear a Second Amendment case that could expand gun rights. And Thomas, the longest-serving member of the court, will likely find himself in the majority.

All along, Thomas has been cultivating his jurisprudence, often in dissent.

Now, he’s lasted long enough to potentially see a shift not only in the areas of abortion and the Second Amendment but also in other key areas, including affirmative action and voting rights.

Thomas has also witnessed Chief Justice John Roberts, ever the incrementalist and the institutionalist, press the brake at times to slow the momentum of the far right side of the bench. Now that Justice Amy Coney Barrett is on the court, Roberts’ role will be diminished. That was already evident this spring in an emergency order when a 5-4 conservative majority moved the needle to the right in a religious liberty case. Roberts was in dissent.

RELATED: How Amy Coney Barrett has changed the Supreme Court in ways Kavanaugh hasn’t

More than any other member of the current court, Thomas is deeply skeptical of the notion of “stare decisis”– a legal term that is roughly translated to mean “stand by the thing decided and not disturb the calm.” It reflects the court’s respect for the accumulated opinions that have been handed down in history as well as the consistent development of legal principles.

Last term he noted, for example, that the court has “recently overruled a number of poorly reasoned precedents that have proved themselves to be unworkable.”

This June, court watchers are on high alert to see if liberal Justice Stephen Breyer retires to clear the path for President Joe Biden to name his first nominee. If Biden does get the chance, he’s probably going to look for someone young enough to spend decades on the bench to influence the law. Thomas, who was just 43 when he was nominated, could, in that respect, serve as a model.

Abortion

It was just last June that Roberts joined with the liberals to strike down a Louisiana abortion law, stunning conservatives. Thomas lashed out.

“Roe is grievously wrong for many reasons,” Thomas wrote, “but the most fundamental is that its core holding—that the Constitution protects a woman’s right to abort her unborn child—finds no support in the text of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

Thomas previously warned in 2019 of the potential that abortion could become a “tool of eugenic manipulation.”

But this week the justices agreed to hear a case next term concerning a Mississippi law that bans most abortions after 15 weeks. Barrett’s vote may have been critical. Supporters of abortion rights rang alarm bells.

“The Supreme Court just agreed to review an abortion ban that unquestionably violates nearly 50 years of Supreme Court precedent and is a test case to overturn Roe v. Wade,” Nancy Northup, the president of the Center for Reproductive Rights, said in a statement.

But conservatives rejoiced. “This is a landmark opportunity for the Supreme Court to recognize the right of states to protect unborn children from the horrors of painful late-term abortions,” said Marjorie Dannenfelser, the president of the Susan B. Anthony List.

The court does not need to formally overturn Roe in order to make a difference. But if it did take that step, abortion access would be left to the individual states. According to the abortion rights research group the Guttmacher Institute, 22 states have laws that could be used to restrict the legal status of abortion.

Second Amendment

In 2008, Thomas signed on to Justice Antonin Scalia’s landmark opinion holding that the Second Amendment protects the individual right to have firearms for self-defense. Supporters of gun rights believed that many gun regulations across the country would fall.

But lower courts, citing a part of the District of Columbia v. Heller decision that said that the “right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited,” allowed for some regulations.

In 2017 Thomas, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch, dissented when the court declined to take up a case that might expand upon Heller. “I find it extremely improbable that the Framers understood the Second Amendment to protect little more than carrying a gun from the bedroom to the kitchen,” he wrote.

Thomas criticized what he called a “distressing trend: the treatment of the Second Amendment as a disfavored right.”

He noted at the time that the court had not heard argument in a Second Amendment case for seven years. “Since that time, we have heard argument in, for example, roughly 35 cases where the question presented turned on the meaning of the First Amendment and 25 cases that turned on the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. ”

Last term, the court again passed over several Second Amendment cases, but on April 26, the justices – presumably because the conservatives thought they had five solid votes with the addition of Barrett – agreed to hear a case next term concerning a New York law that restricts an individual from carrying a concealed handgun in public.

“Few people realize how often Justice Thomas’ solo opinions eventually become majority opinions in the Supreme Court,” said David Kopel, a Second Amendment expert and professor at the University of Denver Law School. “For example, in the 1997 case Printz v. United States, Justice Thomas wrote a concurring opinion saying that some gun control laws might violate the Second Amendment , expressing his hope that the court would one day take a Second Amendment case.” Kopel noted that the court did just that eventually in Heller.

Affirmative action

There is also a good chance that the court revisits affirmative action in the near future. A group called Students for Fair Admissions, for example, is asking the court to hear a case over Harvard’s admissions policy (the school has won at the lower courts). The group is urging the Supreme Court to overturn precedent that has long allowed consideration of race in admissions, specifically a 2003 case called Grutter v. Bollinger.

In 2013, Thomas wrote a concurring opinion in one case saying he thought that Grutter should be overruled and the court should hold that a “state’s use of race in higher education admission decisions is categorically prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause.”

It’s worth noting that the lawyer challenging the Harvard case, William Consovoy, is a former Thomas clerk.

Indeed, Thomas’ influence expands beyond his written word. Former clerks such as former acting Solicitor General Jeff Wall and Patrick Philbin, who served as deputy counsel to the president, had key positions in the Trump administration. And Trump appointed former clerks as judges on powerful appellate courts, including Gregory Katsas, James Ho and Neomi Rao.

Planting more seeds

Thomas has also frequently written alone, provocatively planting more seeds for his colleagues to ponder. In 2019 he called for the reconsideration of a landmark First Amendment case, New York Times v. Sullivan, calling it a policy-driven decision “masquerading as constitutional law.”

Earlier this year, he suggested that Congress consider whether laws should be updated to better regulate social media platforms that he said have come to have “unbridled control” over speech.

In the voting rights context, Thomas dissented after the election when the court denied an appeal from Republicans challenging a Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision that allowed ballots received up to three days after Election Day to be counted to accommodate challenges brought on by the coronavirus pandemic.

“Because the Federal Constitution, not state constitutions, gives state legislatures authority to regulate federal elections, petitioners presented a strong argument that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision violated the Constitution by overriding the clearly expressed intent of the legislature,” Thomas wrote. Election law experts say that if a majority ultimately adopts that position it could have a fundamental impact on the power of state courts to have final word on their states’ voting rules.

Thomas noted that it was “fortunate” that the decision by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court “does not appear to have changed the outcome in any federal election” but said that “we may not be so lucky in the future.” In doing so, he seemed to give at least some credence to supporters of former President Donald Trump who believe that voter fraud is widespread even though most experts say it is not. “For one thing,” Thomas wrote, “as election administrators have long agreed, the risk of fraud is vastly more prevalent for mail-in ballots.”

Thomas’ allies have long waited for the current moment.

“Since he joined the Supreme Court, Justice Thomas has voted to decide cases based on what the law and facts require,” said Tyler Green, a former clerk who currently works for the law firm Consovoy McCarthy. “That makes it all the more satisfying now to see his opinions becoming popular – and shaping entire areas of Supreme Court precedent – precisely because they are right.”