Archaeologists have recovered the bodies of victims of former Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco who were executed and buried at a cemetery in centralSpain.

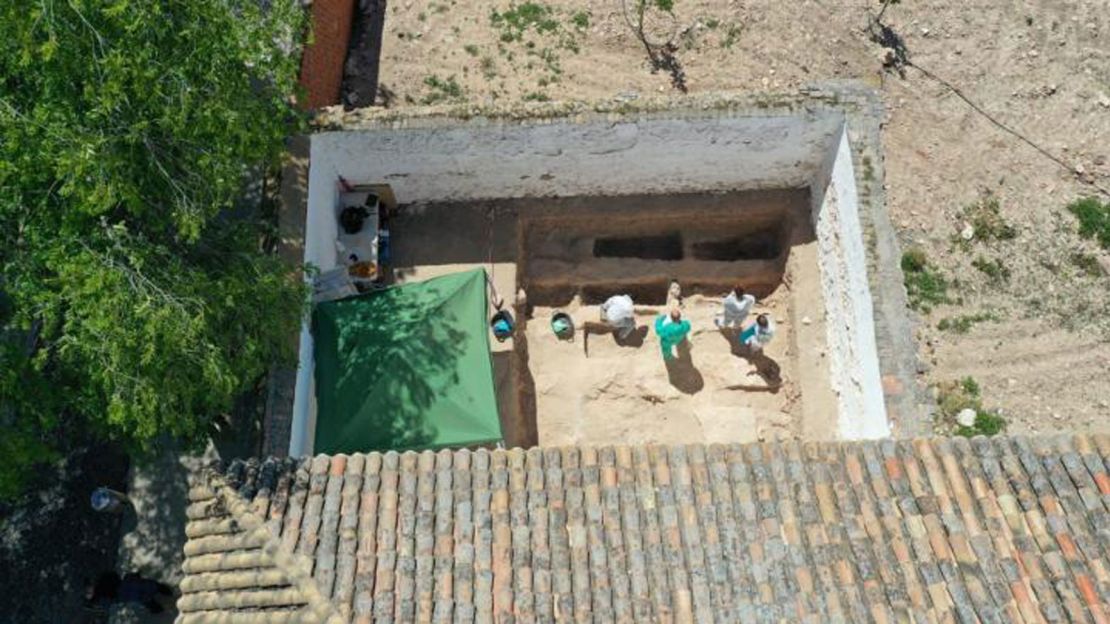

The team of forensic archaeologists and anthropologists are working to find, exhume and identify those who were killed by the Franco regime at the cemetery in the town of Almagro between 1939 and 1940, at the end of the Spanish Civil War, according to a press release from Cranfield University published Monday.

Researchers from Cranfield are working with colleagues from the University Complutense of Madrid (UCM) and Mapas de Memoria (Maps of Memory) at the site in the Ciudad Real province.

Similar efforts around the country have recovered more than 7,000 victims of the Spanish Civil War since 2000, the press release said.

Experts are looking for 26 people in total, with carpenters, teachers and farmers among their number, excavation leader Nicholas Márquez-Grant, senior lecturer in forensic anthropology at Cranfield Forensic Institute, told CNN Tuesday.

Researchers know whose remains are in the cemetery because they are registered as being buried there, but their deaths are listed as natural, rather than executions, he added.

They have already recovered several bodies with gunshot wounds to the head, bits of clothing and other personal effects, such as buttons, a pencil, and a fountain pen, added Márquez-Grant, who said the victims were executed by local right-wing partisans rather than Francoist soldiers.

Family members of the victims have been contacted and it is hoped that DNA analysis can match them and allow for a proper burial of the remains, although matching DNA is not a certainty, said Márquez-Grant.

Some family members have visited the cemetery, where photographs of the victims have been hung up by the researchers.

“It’s quite powerful,” added Márquez-Grant, who said two elderly sisters had visited the site. Their father was executed at the cemetery when they were small children.

Maria Benito Sanchez, director of the scientific team for the project from the School of Legal Medicine at UCM, added in the press release: “As forensic anthropology professionals we have the responsibility of putting our science to the service of the relatives who have been searching for their loved ones for a long time now.”

The team will carry out excavations at the site until the beginning of June, then anthropological and DNA analysis will be carried out until the end of the year to identify the remains.

Jorge Moreno, director of Maps of Memory, said 21 families of victims have been identified relevant to the excavation so far.

The Almagro cemetery site is the largest mass grave opened so far in the province, but there are other larger ones known to hold the remains of hundreds of people.

Franco emerged the winner from Spain’s 1936-39 civil war and ruled the country until his death in 1975. Thousands of executions were carried out by his nationalist regime during the civil war and in the following years.

Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has pledged to support efforts to exhume and identify victims of the civil war. Márquez-Grant said government officials have visited the site in Almagro.

“We’ve now been asked to open more mass graves in the region,” said Márquez-Grant, who hailed the success of a model which involves close cooperation between social anthropologists, forensic anthropologists, forensic archaeologists and geneticists.

Some people in Spain complain that the process has taken far too long and bemoan the fact that many relatives of civil war victims have died before they could recover their remains, but Márquez-Grant says that identifying the victims wouldn’t have been possible in the 1970s or 1980s. “It has come at the right time because we’ve got the science to do this,” he said.