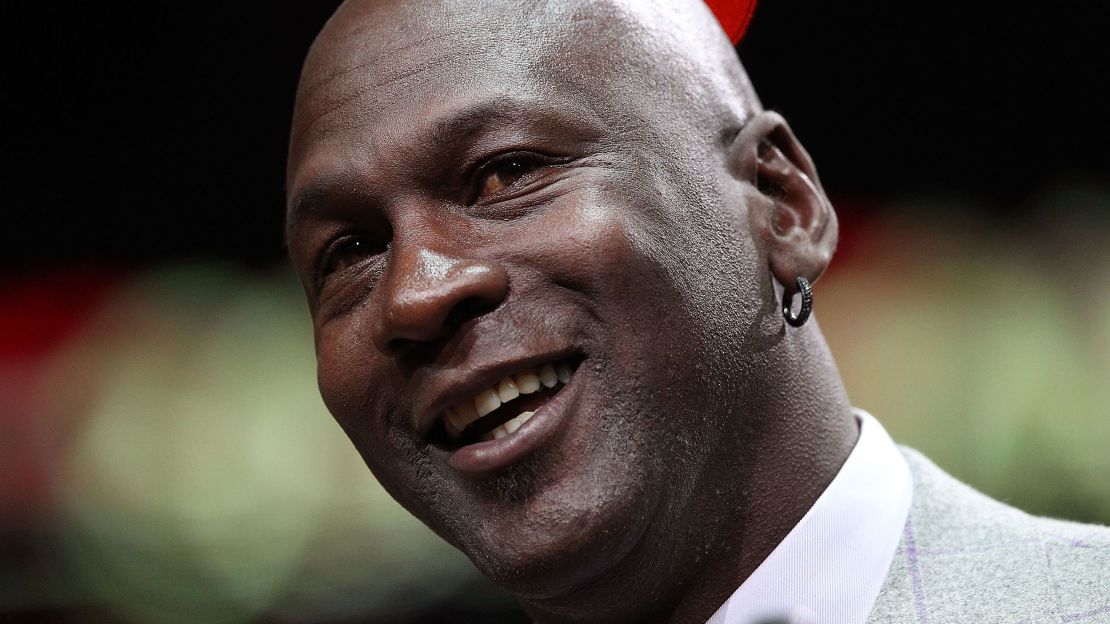

While regarded by many as the greatest basketball player of all time, Michael Jordan’s reticence to speak on issues of social or political importance has always seemed to be a surprising misstep – his one shot that appeared to fall far wide of the basket.

One year after the critically acclaimed docuseries “The Last Dance” brought a renewed focus on Jordan’s career, hindsight and the pivotal events of 2020 may offer insight into why he played it that way.

After the murder of George Floyd, many current and former NBA players were prominent in protesting against racial injustice and voter suppression; Jordan, alongside Nike’s Jordan brand, pledged $100 million over 10 years to organizations dedicated to promoting social justice.

As the fifth wealthiest Black man in America, according to Forbes, Jordan is the NBA’s only Black principal owner. He became the majority owner of the Charlotte Hornets in 2010.

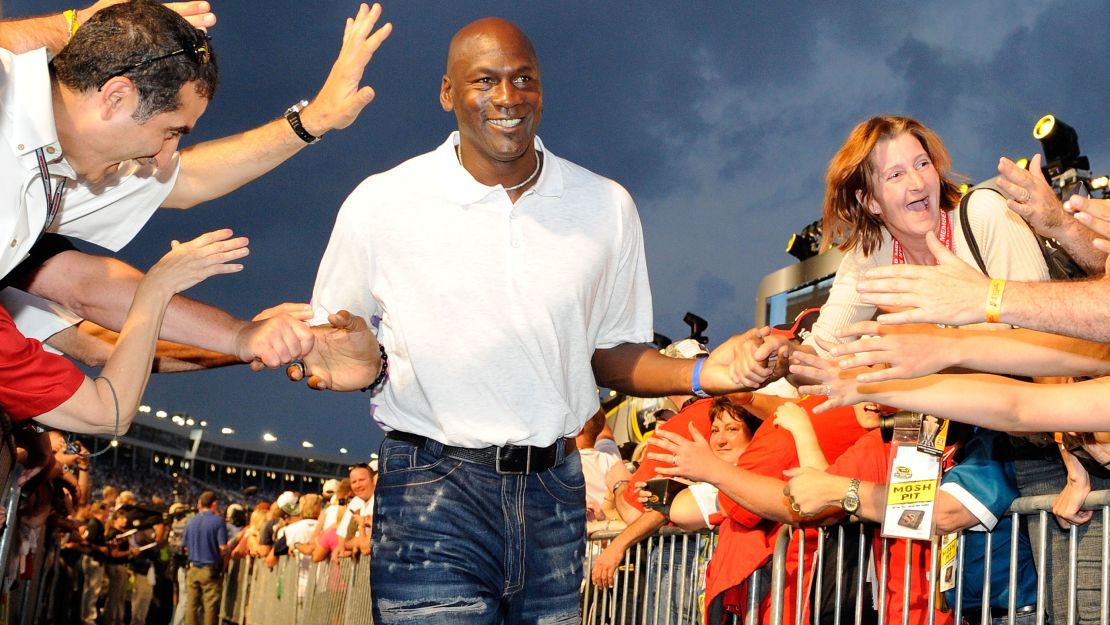

He also helped form NASCAR’s 23XI Racing – which debuted in 2021 – and employed Bubba Wallace, the sport’s only Black driver.

In April of this year, 13-time NBA All-Star Dwyane Wade followed Jordan into the ownership ranks with the Utah Jazz, only weeks after LeBron James announced he’d teamed up with Fenway Sports Group – owner of the Boston Red Sox, Liverpool Football Club and NASCAR’s Roush Fenway Racing team.

Jordan pioneered this potential for sports stars to be not only commercially viable assets, but their own influential force. Amidst all the criticism, he embodies a universal truth – money talks.

Economic advancement

“The most powerful employee in America is the Black athlete.”

Speaking to CNN Sport, Len Elmore – former NBA player turned New York prosecutor, television analyst and senior lecturer at Columbia University – is referencing Howard Bryant, author of “The Heritage: Black Athletes, a Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism.”

“He made a statement that I think is so true,” Elmore continues. “The position of Black athletes, particularly in America, in the two major sports of basketball and football, they are literally, if they understand it, they’re some of the most powerful employees in America.”

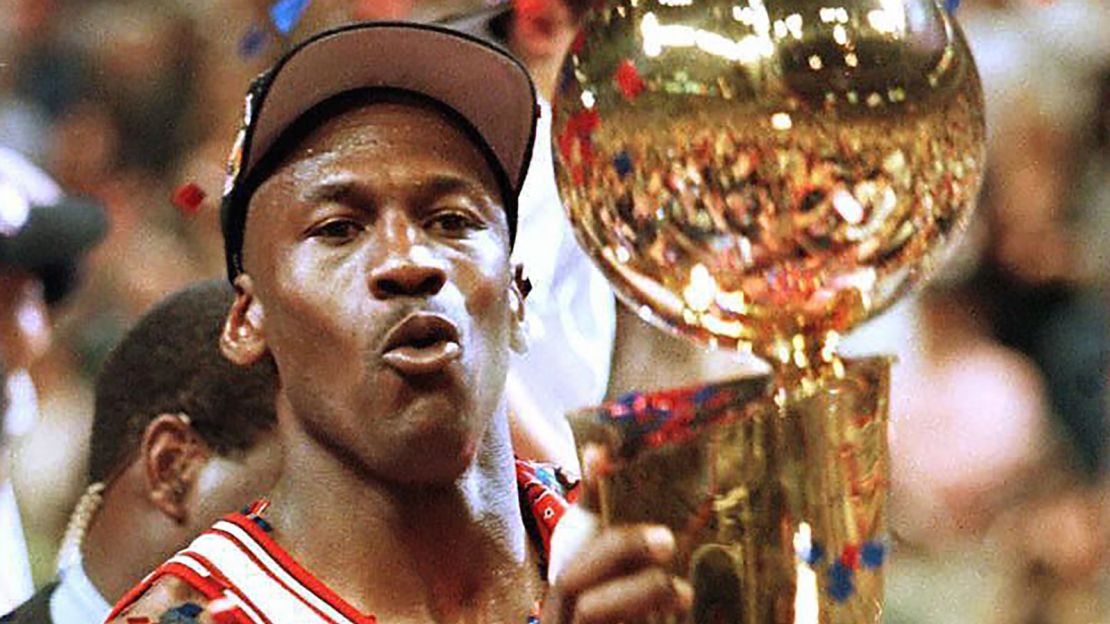

After David Stern took charge of the NBA as commissioner in 1984, he leveraged the huge popularity of stars such as Larry Bird and Magic Johnson to grow the league’s value, increasing revenues from $118 million in the 1982-83 season to $4.6 billion in 2012-2013, according to Forbes.

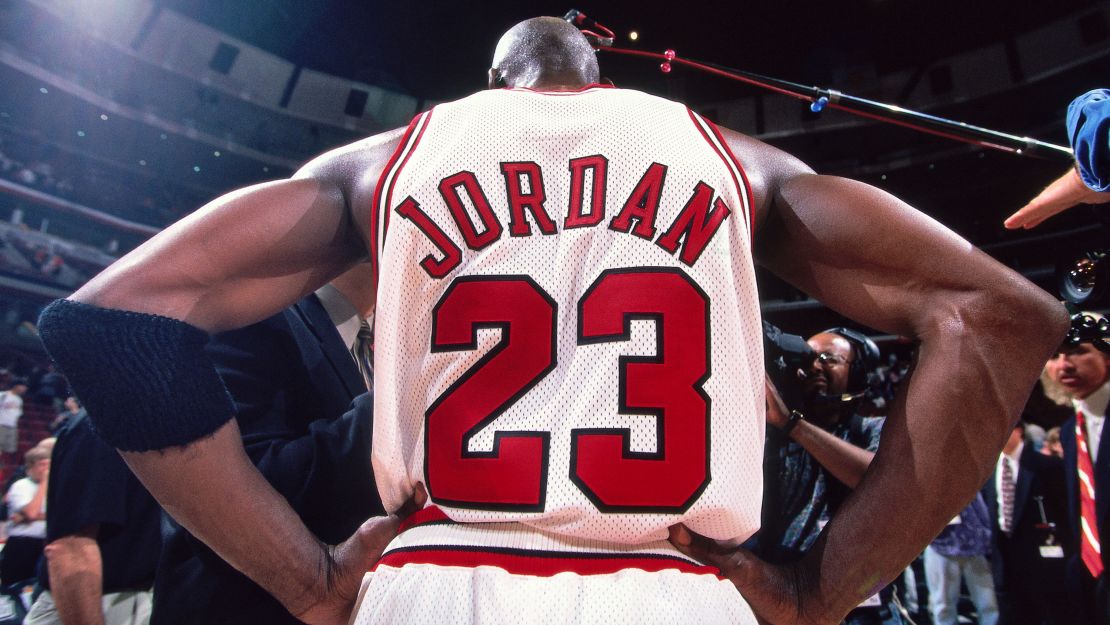

By the time Michael Jordan joined the Chicago Bulls in the 1984 draft, he was already well acquainted with the importance of financial self-dependency. During an era when sharecroppers were still common in North Carolina, his grandfather, Edward Peoples, had owned his own farm, fixated on “economic advancement,” Jordan’s biographer writes.

“Denied any sort of access to the politics of that era,” Roland Lazenby writes in “Michael Jordan: The Life,” “[Peoples] was tireless in his focus on making money.”

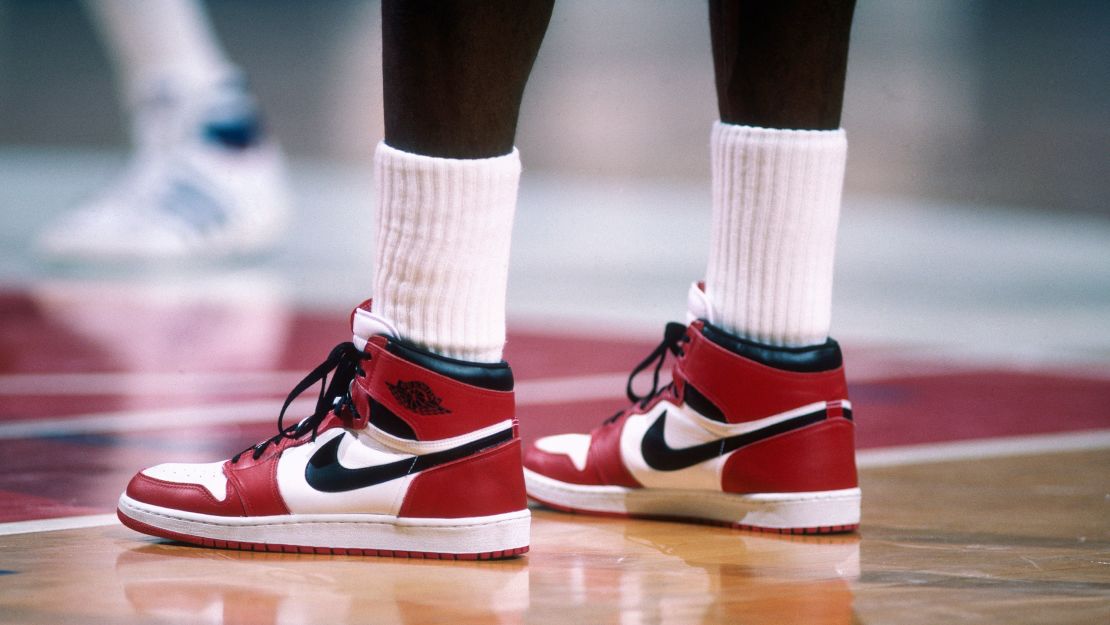

As a rookie, Jordan signed a five-year sneaker deal with Nike in 1984, with an annual pay of $500,000.

According to his agent, David Falk, in “The Last Dance,” “By the end of year four, Nike hoped to make $3 million in sales. But by the end of year one, they’d made $126 million.”

As the 1990 North Carolina Senate race approached, and a request came for Jordan to publicly endorse Democrat Harvey Gantt – Charlotte’s first Black mayor who was trying to unseat Republican Jesse Helms to become the state’s first Black senator – Jordan refused.

“Politics had not been the path to prosperity for his grandfather, Edward Peoples, nor for generations of Black North Carolinians,” Lazenby wrote.

Jordan’s off-the-cuff remark on the team’s bus that “Republicans buy sneakers too” – since labelled a joke – has been a stain on his legacy ever since.

“At the time, many of us shook our heads,” Elmore remembers. “I was past my career. I was now a lawyer, and kind of understood the world even better.

“You shake your head because here is the most prominent athlete in America and the world, and he refused to take a stand against an arch-segregationist who was running for the Senate in North Carolina against a Black man.

“He would not take sides and there was many of us who didn’t understand the totality of the story, the complexity. To many of us, it was like, ‘Why not? Why wouldn’t you, Michael?’

“But now you come to realize, obviously from a leverage standpoint, he had a brand, he had an image he was trying to protect, and it served him well. Look where he is today and what he’s doing. The very many things that he’s done supporting hospitals and children’s causes, etc. He might not have been in a position to do that had he taken a stand at that time.”

As of 2020, Nike had paid Jordan an estimated $1.3 billion since 1984, according to Forbes, with the Jordan brand’s revenue standing at $3.1 billion for the financial year ending May 2019.

The Jordan brand

Todd Boyd, aka Notorious Ph.D., is the Katherine and Frank Price Endowed Chair for the Study of Race and Popular Culture at the University of Southern California and has appeared in numerous documentaries including “The Last Dance” and “Shut Up and Dribble.”

“When you talk about sports in American society, it becomes a conversation about race,” Boyd tells CNN Sport. “And the conversation about race in America is one where Black people have historically been excluded – (or) if not excluded, marginalized.

“The ability of a Black man to participate in capitalism in a way that Michael Jordan was able to participate and become iconic, being attached to brands, is not something that has always existed.

“For a Black man to be at the forefront of expanding the sport and the culture surrounding the sport was a very important series of events that spoke to both the viability of Black athletes, but also their cultural presence beyond their sport and America.”

Jordan increased his recognition off the court by appearing in films such as Warner Bros’ “Space Jam” and Spike Lee’s “He Got Game,” alongside further sponsorship deals including Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Wheaties, Chevrolet, Hanes, Gatorade and Upper Deck. (Warner Bros., like CNN, is owned by WarnerMedia.)

Such endorsements grew his fortune – far outweighing his $94 million playing earnings over 15 seasons in the NBA, as reported by Forbes – and enabled investments that ranged from tequila, a car dealership, and a series of branded restaurants to the group behind the MLB’s Miami Marlins and aXiomatic, the parent company of esports’ Team Liquid.

Basketball is Jordan’s largest financial commitment, and as the NBA’s only Black principal owner with the Charlotte Hornets, he has overseen a valuation increase from $175 million to $1.5 billion, according to Forbes.

The wealth that Jordan has amassed from sport, endorsements and investments has afforded him the opportunity for a range of philanthropic ventures, including a recent announcement of three grants to institutions as part of Jordan’s Black Community Commitment – an initiative he shares with his brand.

The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture will receive $3 million over three years, Morehouse College $1 million over two years, and the Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting $1 million over two years.

Commenting in the press release, Jordan said, “Education is crucial for understanding the Black experience today. We want to help people understand the truth of our past and help tell the stories that will shape our future.”

Jordan’s previous donations vary from $7 million to family health clinics in Charlotte, $5 million to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History, and $2 million profits from “The Last Dance” docuseries to food bank charity Feeding America.

In 2016, Jordan said that he “can no longer stay silent” in a rare, public statement reacting to shootings of Black Americans and the targeting of police officers, committing $1 million each to the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and the Institute for Community-Police Relations.

A place in history

Ever since professional sport was introduced to the US in the decade following the Civil War, athletes have lent their voices to the social issues of their time.

Figures such as Rose Robinson and Muhammad Ali all fall into a continuum of activism as outlined by Harry Edwards, founder of the Olympic Project for Human Rights and professor emeritus of sociology at University of California, Berkeley.

Speaking recently on “The Bakari Sellers Podcast,” and discussing what Sellers categorized as “the Jordan era” – framed by Edwards as the time between 1972 with Jim Brown, Bill Russell, and Ali, to 2012 with Colin Kaepernick and the Black Lives Matter movement – to be popularized as lacking in activism, “there was an era where the foundations for power were laid,” Edwards said.

“When you look at Magic Johnson, when you look at Charles Barkley, when you look at Michael Jordan,” Edwards said, “don’t sell them short because the reality is if they had been activists, they never would have been able to achieve the status and the power that they achieved.”

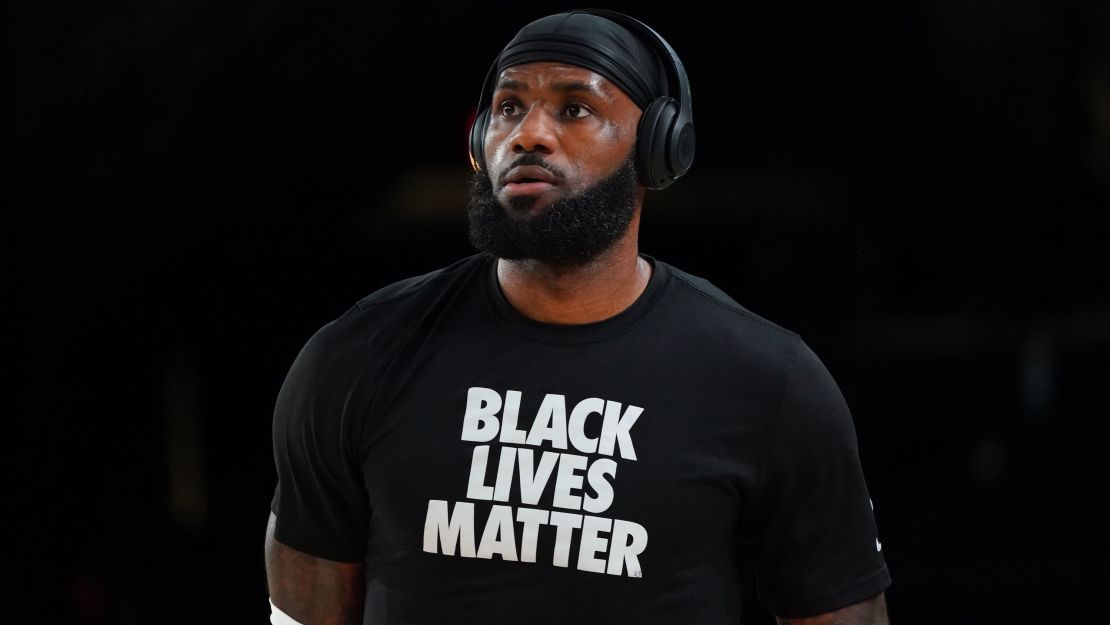

Boyd admits that current athletes, such as the prominent activist and NBA star LeBron James, reap the benefits of advances made by their sporting predecessors like Jordan.

“What we’re living through now,” Boyd says, “it’s great to see these athletes be so actively involved in social and political issues using the platform of social media that hadn’t always existed to have their voices heard.

“Taking actions in a variety of forms – be it Kaepernick or NBA players in the bubble last fall deciding not to play, other athletes joining in, in support – none of this would be possible if they didn’t build on what came before it.

“I see this as a kind of 60-year evolution, if you will. What we’re seeing now is contemporary, but it’s built on history and so that point about there needing to be a power base, we’re not talking about LeBron and a lot of these other individuals if not for what came before them, even if what came before them didn’t always manifest itself in the same way.”

The progression of former players – Grant Hill at the Atlanta Hawks, Wade at the Utah Jazz and Jordan himself – into ownership positions diversifies power in the sport, but Elmore warns of the restrictions inherent in organizations such as the NBA.

“These [leagues] are still clubs,” he says. “They still have boards of governors and it’s still up to those boards to allow permission for people to join those clubs.”

In contrast the freedom and authority of an individual commercially valued player was demonstrated by Steph Curry, in 2017, as his Under Armour deal gave extra weight to his public rebuke of CEO Kevin Plank’s favorable comments of then-US President Donald Trump. The executive, who had called Trump “a real asset,” subsequently took out a full-page newspaper advertisement stating that his comments “did not accurately reflect my intent.”

“He disagreed with the owner of the company and was outspoken enough where it forced an apology,” Elmore recalls. “It forced the owner to take a step backwards. Remember, he’s just a paid endorser, but his power in many ways was greater than the owner of the company.”

“The heartening part of it,” Elmore adds, “is that these young men are growing extraordinarily wealthy and they’re starting to recognize the power that that wealth carries, and so, in building wealth, they can also develop influence.”

The commercial potential that Jordan first exhibited changed the sporting market, and twelve years after Jordan’s first contract in 1984, Nike signed Tiger Woods in a deal reported by Forbes to be worth $40 million over five years – the same price attributed to Serena Williams’ deal in 2003, according to The New York Times.

Fellow tennis star Naomi Osaka signed with Nike in 2019, earning more than $10 million a year in a deal running to 2025, according to Forbes, and Osaka and Williams have become team owners in the National Women’s Soccer League, with the North Carolina Courage and a yet unnamed team based in Los Angeles, respectively.

LeBron James – who has been open with his hopes to buy into an NBA franchise after his playing career – recently helped WNBA star Renee Montgomery with her group’s bid to purchase the Atlanta Dream after players united against former US senator and then-team co-owner Kelly Loeffler following her criticism of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Boyd sees it all as progression. “This is something that’s on the players’ radar now that when their playing days are over, ownership is a possibility,” he says. “Not everybody’s in a position to do that and maybe not to the same extent.

“LeBron and Michael stand out because they’re exceptions, but the fact ownership is on someone’s mind tells us that things have changed. My generation, guys were talking about opening up barbershops and car washes, maybe nightclubs, and that was applauded, that was like, ‘Oh, cool.’ That’s what was considered possible.

“These things that Michael ended up doing, nobody could conceive of that. But then Michael did it, other players did what they did as well and, before you know it, this is possible. A guy who looks like Michael Jordan can become one of the biggest celebrities in the world.

“I don’t want to dismiss people who said they want to own a barbershop – owning any kind of business at the time was thought to be the way to go. It is just an indication people were thinking a lot smaller. It’s different owning a barbershop than owning an NBA team.

“We have to appreciate what has happened to make someone dream differently.”