Athletes are trained to be tough; they’ve learned to push through the pain barrier and find courage when all hope might seem to be lost.

But athletes in Iran have to be braver than most. For them, the battle isn’t just on the field of play, it’s also away from the arenas, where the consequences of their actions could be painful, even deadly.

“I am 100% fearful,” judoka Vahid Sarlak tells CNN Sport. He knows fighting for his beliefs could end badly in a country where political activists and their families are routinely intimidated, arrested and can even be executed.

“Every day, my mom asks me not to do this, she is worried daily. But I say, ‘I was born once, and I’ll die once.’ I have sworn that I’ll fight for my freedom for as long as I’m alive.”

When asked to detail the kind of threats that she is facing, the soccer player Shiva Amini tries to make light of it, telling CNN: “SMS messages, such as ‘We will cut your head off and send a picture of it to your family.’ Do you want just one example, or do you want to hear the rest?”

They used to say that sport and politics shouldn’t mix, but those days seem to be a distant memory. In many parts of the western world, athletes are now using their platforms to shape social and political discourse.

In Iran, sport and politics have always mixed, but it’s the theocratic government that makes the rules and enforces them through fear.

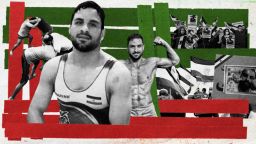

The former junior world champion wrestler Sardar Pashaei knows exactly what can be at stake; he campaigned to try and save the life of wrestler Navid Afkari, who was executed in 2020.

Afkari’s death became a rallying cry for athletes in Iran to unite and push for change in a campaign called ‘United for Navid.’

“If we be silenced today, we don’t have anything to tell our children tomorrow,” Pashaei told CNN.

All three are now living in self-imposed exile abroad, where it’s a little safer to be outspoken; all are brave, but all have been traumatized by years of harassment and intimidation.

When asked if he fears for his life, the former karate international champion Mahdi Jafargholizadeh scoffed at the suggestion: “I died 20 years ago. I lost everything when I was in Iran. If you kill me again, you just killed a dead person.”

An eternal blow

Sarlak might be a judoka, but he could easily have been a poet.

“Have you ever been in love?” he asked CNN Sport. “Sport is love,” he opined. “When you meet a girl for the first time, fall in love and then lose her, would it mean that you will never fall in love again? I’m sure you will, 100% sure. The next love will come.”

At the age of 40, Sarlak is still madly in love with his sport. He says a life without sport would feel “the same as death.” But he’s had his heart broken more than once and in ways that most athletes couldn’t even begin to imagine.

At the age of 17, he says he was ordered to lose by his team at the World Junior Championships. Deliberately losing is an alien concept to any athlete but it’s not for Iranian athletes in international competitions.

When entering a tournament, they don’t fear the prospect of running into a stronger opponent, their biggest concern is that an Israeli athlete lies ahead of them in the draw because their government’s unwritten rule means that they’re not going to be allowed to compete against them.

Sarlak says that the first time he was told to lose in 1998, he didn’t give it much thought – he was still so young. But when it happened at the 2005 World Championships in Cairo, he was absolutely devastated.

“It was the most difficult moment of my life,” he recalled. “I was just crying and asking why? Why should I lose? I remember my coach slapped me and told me: ‘You know that you have to go and lose the match.’”

Other stories by Don Riddell

Sarlak was fighting in the 60kg repechage and on course for a bronze medal; he’d been drawn against an opponent from Azerbaijan, but Israel’s Gal Yekutiel was up next.

His coach delivered the news that no athlete would ever want to hear: “Your next opponent will be an Israeli, and we are not permitted to be in a match with Israelis.”

Nearly 16 years after the event, Sarlak is still traumatized by it and the details of that day have been seared into his memory.

He says that the broadcast cameras were trained on him because they realized he’d thrown the match. His coach put a towel over his head and he was rushed back to the hotel, denying him the chance to watch the rest of the competition.

“I broke all the windows in my room,” recalls Sarlak. “It was the worst day of my life. A hole opened inside of me and that hole is still open. The dream of having that medal has remained with me. I will never forgive them.”

To add insult to injury, Sarlak says he’s still taunted about it.

“Even now, when I see my Azeri opponent, he tells me, ‘Your medal is on display at my house. Your medal is on my neck now. You didn’t want it and I won it.’ This will never be erased from my mind.”

CNN has asked the Iranian government if it acknowledges that it has prevented athletes from competing against Israelis. We also asked if they will allow their athletes to compete against Israeli opponents at the Olympics this year. They have not responded to our inquiry.

‘I’m not going back’

Jafargholizadeh had always wanted to be a karate champion. He says his father was the head coach of the national team, but he didn’t believe in his son.

“I remember one day I was wearing his national team jacket,” Jafargholizadeh told CNN Sport. “He just slapped me in the face and said, ‘Who the hell are you? You get it yourself.’”

That was all the motivation that Mahdi needed. “OK, I said, I’ll show you.”

He was barely a teenager when one of the top teams in the country took an interest in him, and in time, he was competing internationally – a national champion picking up more than 20 medals all over the world.

But Jafargholizadeh says it all came to a screeching halt when he was thrown in jail in 2004, arrested at the airport and accused of planning to be an Israeli spy. He says he was tortured and interrogated for five to six months and even threatened with the death penalty.

Tokyo 2020

He relays the experience in a stream of consciousness and a smile that belies the suffering he endured.

“They break my nose, many different stuff that I don’t even want to talk about.”

He says the accusations were so incredulous that he didn’t take them seriously at first, but it reached a point where he couldn’t take it anymore and he started goading his tormentors to go make good on their threats.

“I never forget that I had a shirt with buttons,” he recalled, gesturing that he ripped it open and declared: “Take your gun and shoot me here now. Or you want to hang me later on? Do it now!”

It’s scarcely believable that Jafargholizadeh was eventually released from jail and able to resume his competitive career at the top level, fighting again at the 2005 and 2007 Asian championships and winning gold and silver medals with his team.

But after another brush with authority in 2008, he realized that it was no longer safe for him to remain in the country. His opposition to the government in Iran wasn’t much of a secret, and he was perhaps something of a marked man.

According to Jafargholizadeh, the President of the Karate Federation, a man “who has been in the intelligence service for years and years,” saw him with tattoos all over his body and declared it would be his last year with the national team.

“I take my last chance; I’m not going back again. I didn’t go back. I left the national team in Germany and became a refugee,” said Jafargholizadeh.

Forced to forfeit

Many young Iranians dream of becoming professional athletes, but they can’t imagine the pitfalls that will come with their exposure to the international community.

“Every Iranian has a passport,” explains Sarlak. “On the first page, it is written that you can travel to any country you would like to go – except ‘the occupied Palestine.’”

Sarlak says even speaking the name Israel just isn’t done in Iran.

“We all know that, but the intensity of this problem is more obvious with athletes because we face situations with Israel. Ordinary people may not have to deal with it, [but] this problem is a flashpoint for athletes that will never go away.”

It’s well known that athletes from Iran are prevented from competing against Israelis – in any competition.

In the main sports where they could have met at the Olympics – boxing, judo, taekwondo and wrestling – there has never once been a contest between athletes from either country.

It almost happened at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, when a swimmer from each country was drawn to race in the fourth heat of the first round of the 100-meter breaststroke. But the Iranian swimmer, Mohammad Alirezaei, never showed up.

In 2017, the wrestler Alireza Mohammad Karimimachiani was in a winning position against Russia’s Alikhan Zhabrailov at the Under-23 World Championship in Poland, when his coach became animated on the sideline.

He can be seen and heard on the broadcast highlights calling from the floor: “Lose Ali!” The clip, which can still be viewed at UWW.Org, reveals an increasingly desperate coach imploring his athlete to throw in the towel: “Alireza! Lose Alireza! Alireza! You must lose! Alireza, you must lose! Israel won. Israel has won.”

The Israeli Uri Kalashnikov had just beaten the American Samuel Brooks and was awaiting the winner in the next round. It was the second time in his career that Karimimachiani says he had been told to lose, later he told the semi-official Iranian Students News Agency that “my whole world seemed to come to an end.”

A much clearer instruction can be heard in an audio recording made at the 2019 World Judo Championships in Tokyo, when Saeid Mollaei was ordered to lose his semifinal in order to steer clear of the Israeli world champion Sagi Muki.

“Based on my stance, that of the regime and that of the minister, he has no right to compete,” says the president of Iran’s Judo Federation in the recording.

The ambient noise of the competition is audible in the background as he concludes with a scarcely veiled threat: “The circumstances stipulate that one should never question this stance. Make him understand that he has no right to compete under no circumstances. He is responsible for his actions.”

Sarlak now lives in Germany; he breaks down in tears and leaves the interview when explaining that he hasn’t been able to see his parents for 12 years. Jafargholizadeh resides in the mountains of Finland and the 1998 junior world Greco-Roman wrestling champion Pashaei is exiled in the US.

He fled in 2008, when it became apparent that his Kurdish ethnicity and the connection to his politically active father was shutting down career opportunities.

As a coach, he says he was barred from traveling out of the country with the national team.

A year before he made the decision to flee the country, he witnessed one of his wrestlers being denied the chance to fight; he told CNN that he watched from a distance as Babak Ghorbani was given the news.

“He was sitting on the stage in the stadium and he couldn’t believe it. He was crying and crying. He was telling me, ‘You know how hard I worked! I don’t deserve this!’

“This is not just about losing one match, it affects your whole life. Your dignity has been taken away by other people, people who are usually members of the intelligence service who don’t know the pain of being an athlete. This is sport, it has to be about peace and friendship, but they teach you to hate.”

‘Girls had no value’

Many countries would be delighted to see their athletes and teams triumph on the world stage.

In the purest sense, sporting success can be a boost to domestic morale, but it can also be used as a means of wielding soft power on the international stage. Sport is a good way to make friends and influence people – and so they’re willing to make heavy investments or even cheat to achieve those ends.

Iranian athletes have come to realize, though, that the opposite is true for them. Iran seems to routinely sabotage its own sporting success and its female athletes are in no doubt about that.

They often feel as though they have to compete with one hand tied behind their backs – that’s if they’re allowed to compete at all.

Since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, Iran hasn’t sent a female athlete to compete at the Olympics in swimming, wrestling or gymnastics, none of which would be possible while wearing the compulsory hijab.

Shiva Amini says her proudest achievement with the national women’s soccer team was at the 2009 Indoor Asian Games in Vietnam, where her Futsal team beat Uzbekistan and Japan to win their group, before losing to Jordan in the semifinals.

“With all the difficulties of wearing a hijab, in the heat in Vietnam, we were able to win,” she explained to CNN. “Despite all the difficulties, because of the love we have for football and sport, we could fight and be just like any other girls.”

Amini details the inconvenience of competing in a hijab, how it restricts the ability to move and how it becomes heavy with sweat: “We had a hard time even breathing.”

And if the scarf became loose or if the sleeves rolled up their arms, the referee would blow the whistle to stop the game and a scoring opportunity might have been lost.

Amini, who was regarded as the most technically gifted player in the women’s game in Iran, says that she and the female team were made to feel as if their status was little more than token.

Long reads

“I started to realize that I am in a society that they fundamentally do not want a girl to advance,” she said, outlining the experience of sharing a national training camp with the men’s team and being told to remain on the sidelines.

“I asked the head of the federation why you aren’t giving us the facilities and he responded by saying, ‘The team only exists so that FIFA [football’s world governing body] wouldn’t eliminate the boys team according to their regulations.’ I realized that us girls had no value. It was an insult and a humiliation.”

In 2017, Amini was playing football in Switzerland and she posted pictures of it on her social media accounts.

Given that she wasn’t on official business with the country of Iran, she didn’t give it a second thought, until the pictures appeared everywhere back home and caused a storm of controversy: she wasn’t wearing her hijab and she was playing with “anti-Islam” teams.

“For a few weeks, the entire internet was filled with stories about me,” Amini told CNN. “It created a very bad situation for my family in Iran and myself in Switzerland.”

She hired lawyers in both countries, but soon came to realize that the situation was now beyond her control.

“They have fully politicized this event and put your name on a blacklist in Iran,” she said she was told. “I was not prepared to deal with what was about to happen, my life was about to fully change in all aspects, I did not have a good mental condition.”

Amini has not been home since and says both she and her family are routinely harassed and intimidated.

Campaigning for justice

In September 2020, a dreadful event motivated these four athletes and many others to come together and tell their stories.

The execution of wrestler Afkari – capital punishment for a murder that his family and friends say that he did not commit – galvanized the sports community and spurred it into action.

Within the last few months, the United for Navid Campaign has been writing to Thomas Bach, President of the International Olympic Committee and the Executive Board at the IOC, calling for immediate action to be taken against the National Olympic Committee of Iran.

In letters sent on March 5, March 25 and April 19, United for Navid has provided the names and case studies of 20 athletes who’ve been negatively impacted by political interference in Iran.

“We have a simple question,” states the United for Navid campaign spokesman Pashaei: “Can IOC member states torture and arrest athletes and violate the [Olympic] charter? Are you doing anything to protect these athletes? Because their rights are being discriminated against every single day.”

According to the charter’s Fundamental Principles of Olympism, “the practice of sport is a human right” and “sports organizations within the Olympic Movement shall apply political neutrality.”

Access to sport should be enjoyed without “discrimination of any kind, such as race, color, sex, sexual orientation, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

The charter concludes: “Belonging to the Olympic Movement requires compliance with the Olympic Charter.”

In an impassioned plea, the emotion is clear in Pashaei’s voice as he continues listing to CNN the many ways in which the integrity and safety of Iranian athletes is compromised by their own government.

“When they don’t compete with Israeli athletes, they tell the IOC that this is their personal decision. It’s a big lie. Every single trip, there are members of security intelligence watching the athletes 24/7 and if they do something wrong, they have been punished.

“I want to ask IOC, are you aware of this? You talk about gender equality and race equality. Are you aware that one of your members is violating the charter all the time? You have been silent about this; we’re not going to be silenced.”

Of the 20 case studies that have been sent to the IOC so far, only 12 athletes have been identified. The names of eight others have been withheld to protect them, as they are still living in Iran.

Amini says those athletes fully support the campaign. “They are very happy with this movement. They encourage us, they push us forward. And the one thing they all say is, ‘All of our hopes are in you guys,’” Amini told CNN.

There is an element of risk, also, for the athletes living outside of Iran – many of them still have family at home.

“Once in a while they question our parents, brothers and sisters, they threaten them,” says Pashaei. “But our families, all of them, believe that we’re doing the right thing.”

So far, the IOC’s only response has been a tacit acknowledgment that they have received the documentation from the campaign.

In a March press conference, spokesman Mark Adams said: “I don’t know to be honest, I think – I believe – we have. And as with all communications, it will be dealt with in due course, but it wasn’t discussed at the Executive Board today. But trust us, it will be dealt with.”

United for Navid is optimistic that the IOC will, ultimately, take action.

Earlier this year, their pressure campaign led to the International Judo Federation banning the Iran team for four years, but they’re hoping that the action can be urgent.

In the letter dated March 25, Pashaei concludes with the line, “We look forward to your timely response. Every day that passes without action results in more athlete mistreatment.”

Pashaei says there is evidence to suggest that the current head of Iran’s Olympic Committee used to be a top-ranking member of Iran’s intelligence agency, as detailed in a 2018 report from VOA/Radio Farda: “He was involved in arresting and torturing people. He is going to the Olympic Games.”

“Even a little change will make a big difference,” concludes Jafargholizadeh. He and the other campaigners are confident that action from arguably the biggest governing body in world sport would force Iran to take politics out of sport and treat the athletes better.

But it might take an Olympic ban to do it.

“A lot of people think we are against sport in Iran,” he said, disputing that fact. “They have to know we have been athletes. We have been part of that national team for years and years. We just want to say, ‘Stop torturing people and killing them.’”

“It’s about our dignity,” says Pashaei. “We’re not going to give up. We’re going to go to the end.”