Plagued by climate change-fueled drought and increasing demand for water, Lake Powell, the second largest reservoir in the United States, has fallen to its lowest level on record since it was first filled more than 50 years ago.

As of Sunday, Lake Powell had fallen to roughly 3,554 feet in elevation — just 33% of capacity — according to the US Bureau of Reclamation, below the previous all-time low set in 2005.

Lake Powell and nearby Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, have drained at an alarming rate this year. The two reservoirs fed by the Colorado River watershed provide a critical supply of drinking water and irrigation for many across the region, including rural farms, ranches and native communities.

The significance of the dwindling supply in both reservoirs cannot be overstated. Water flowing down the Colorado River fills the two reservoirs, which are part of a river system that supplies over 40 million people living across seven Western states and Mexico.

A study by US Geological Survey scientists published in 2020 found that on average, the Colorado River’s flow has declined by about 20% over the last century, and over half of that decline can be attributed to warming temperatures across the basin.

John Fleck, the director of the Water Resources Program at the University of New Mexico, told Lake Powell might not be the larger of the two major Colorado River reservoirs, but it plays a significant role in the West’s water crisis.

“The bottom dropping out on Lake Powell may be the more serious challenge, because a buffer in Lake Powell allows you to move water down to Lake Mead to make up for the shortcomings,” said Fleck.

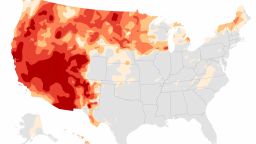

The dwindling reservoir levels come as more than 95% of the Western US is experiencing drought conditions, the largest area since the creation of the US Drought Monitor. More than 28% of the region is experiencing exceptional drought, the most severe level of dryness.

If Lake Powell is projected to drop below 3,525 feet, the Bureau of Reclamation can release more water to Lake Powell from upstream reservoirs as part of the 2019 Colorado River Drought-Contingency Plan. Emergency releases from such upstream reservoirs, particularly the Blue Mesa Reservoir in southwest Colorado, are set to begin in August.

Much like Lake Mead and Hoover Dam, Lake Powell’s plunging water level threatens Glen Canyon Dam’s capacity to produce hydropower for many states including Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and Nebraska.

And if the next major study in August from the Bureau of Reclamation projects an even worse water level decline in both Lake Powell and Lake Mead, it would trigger the first-ever shortage declaration on the Colorado River, meaning many communities would begin to see their water supply significantly slashed next year.

While major cities may be prepared for the current drought-fueled water shortage, Fleck said the rapidly warming climate may challenge their emergency preparedness.

“Over time, cities are going to need to conserve more and more water,” he said, “and that doesn’t get any easier with climate change.”

Correction: A previous version of this story included a map that showed an incorrect location for Denver. The map has been removed.

CNN’s Drew Kann contributed to this report.