Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Mammoths covered huge distances in their lifetime. The beasts traveled the equivalent of the circumference of the Earth almost twice, information from the study of a 17,000-year-old tusk has revealed.

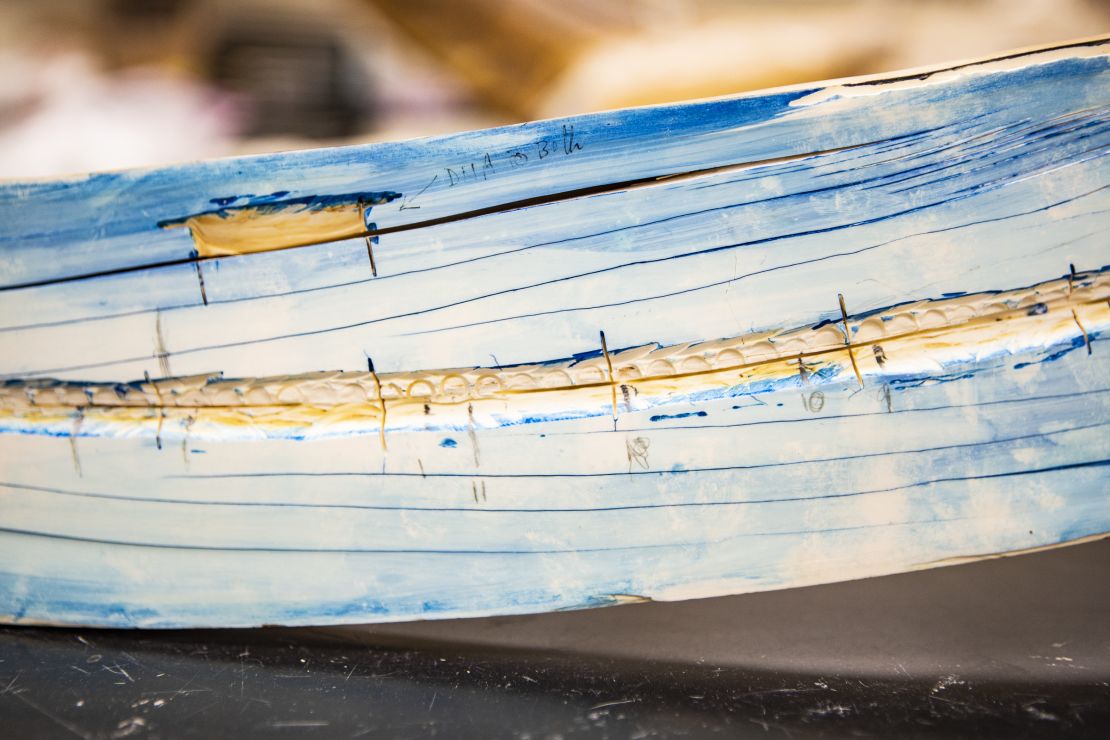

Mammoth tusks grow by age – a bit like tree rings – and analysis of chemical traces in each layer of growth can show surprising details. Researchers split lengthwise a 6-foot (2-meter) tusk that belonged to the University of Alaska Museum of the North and extracted 400,000 microscopic samples from the tusk.

“The detailed microsampling done here, and the resolution of the results enabling the team to track a long-dead animal’s movement in detail, are unprecedented! It’s absolutely amazing that the researchers could essentially follow this male mammoth’s movements across different years,” said Love Dalén, a professor of evolutionary genetics at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Stockholm, who wasn’t involved in the research, via email.

The technique used by the researchers allows them to pinpoint where the mammoth has been drinking water or eating plants by looking at different signatures of elements called isotopes.

“The ratio between these different variants, such as strontium isotopes, differs between regions. Since tusks grow by age, one can therefore take minute samples along the tusk, where each sample represents a particular time-period of the mammoth’s age,” Dalen explained.

The mammoth visited many parts of Alaska at different points during its lifetime, said Matthew Wooller, the senior author of the paper that published in the journal Science on Thursday.

The researchers were able to compare the chemical changes in the tusk with a chemical map of Alaska they compiled by analyzing the teeth of hundreds of small rodents from across Alaska held in the museum’s collections. The rodents travel relatively small distances during their lifetimes and represent local isotope signals, according to a news statement.

Many things might have prompted the ice age animal to move such large distances, said Wooller, a professor and paleoecologist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“Mammoth are large grazers and they need to keep moving to find fresh patches of food. Mature male mammoths like the one we studied also need to try and find a female to mate with,” he said via email.

The movement could also be seasonal, he added.

“These include the obvious changes in temperature that occur with the seasonal transition from winter to summer – but also these seasonal changes can bring a change in the intensity of harassment by mosquitoes and other biting flies in the growing season. Higher windier locations can some times provide a relief from these insects during the growing season.”

Dalen said it was likely not just male mammoths that were highly mobile, but also matriarchal herds that made seasonal migrations.

“The results show that when it was a juvenile (and still likely dependent on its mother’s herd), this mammoth repeatedly moved north and south,” he said.

“In very easy layman’s terms, mammoths appear to have been the original ‘Ice Road Truckers,’ moving northwards and southwards across the Brooks range, between interior Alaska and the North Slope,” said Dalen, referring to the TV show that features truck drivers making long journeys on ice in Alaska and Canada, via email.

Mammoths went extinct about 10,000 years ago, although isolated populations held on till 4,000 years ago. While the study doesn’t directly shed light on why, it suggested that maintaining a similar degree of mobility as the climate changed to the warmer and wetter pattern we have today could have imparted additional stress as the mammoth encountered unfamiliar environments or restricted its movement. The last remaining mammoth populations lived on Wrangel Island, a small island in the Arctic Ocean off the coast of Siberia, where large-scale movement would not have been possible.

The diary written in thetusk samples analyzed by the study team showed an abrupt shift at about age 15, which probably coincided with the mammoth being kicked out of its herd, mirroring a pattern seen in some modern-day male elephants, the researchers said.

The mammoth died at the age of 28 on Alaska’s North Slope above the Arctic Circle, where its remains were excavated. Nitrogen isotopes in its tusks spiked during the final winter of its life – a signal that can be a hallmark of starvation in mammals.